Lord British is now Lord Blockchain

The RPG pioneer's next game Effigy embraces the tech, but with many caveats.

Richard Garriott is one of the most influential and successful RPG designers in history. He'll be forever associated with the Ultima series, which he began in 1981 with what is considered both a pioneering work for RPG design and the first open world game. Garriott would ultimately design and direct nine mainline Ultima games as well as Ultima Online—again, a pioneer in MMO design—before a spell at NCSoft, the main product of which was the ill-fated Tabula Rasa (and a later lawsuit).

As if that wasn't enough for one lifetime, Garriott is also an astronaut: He took a self-funded space flight in 2008, following in the footsteps of his astronaut father Owen Garriott. Garriott participated in the first zero gravity wedding in June 2009 with his wife Laetitia Garriott de Cayeux. More recently, last year Garriott travelled to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, and was elected president of the Explorers' Club.

With all that other stuff going on, Garriott's role in the games industry has become more marginal—whereas three decades ago he was right at the centre of its future, now his most recent project is the kickstarter-funded RPG Shroud of the Avatar. Yes, it was a bit like Ultima—Garriott sold the rights to the series to EA in 1992, but the publisher has shown little interest in using the licence since the disastrous mobile spin-off Ultima Forever in 2012.

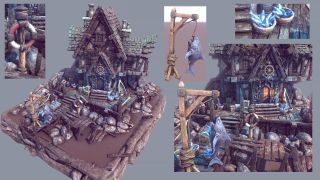

Garriott and industry veteran Todd Porter (a designer on Ultima 6) are now working on a new game that's about to break cover, with the working title Effigy. Brace yourself: it uses the blockchain. Though as Lord British explained in our interview, it's not the same pitch we've seen with most blockchain-based games so far.

PC Gamer: What's the idea behind the game?

Richard Garriott: It is an MMO. We're being very careful to call it 'inspired' by the shared Ultima history that Todd and I have. Before we got this going, we sat back and we reviewed all of our work together to say 'what are the things that we both believe worked in the past that have not been expanded on in the modern times, what both of us never got a chance to contribute in games.' And then talked a lot about the state of the art. There's some really great role-playing games that are out there that I really admire, whether that's things like Red Dead Redemption or The Witcher, but we're really beginning to see story craft in multiplayer role-playing settings that does what I described earlier that great art does: which is to hold up a mirror to either your personal, or the human, contemporary social conditions, and really makes you think about life.

Todd Porter: The game is going to be overhead: think of Diablo if you think of the perspective. We have a lot of fresh new things that we're going to be doing in terms of how we shard the game and how we create that experience. We've hired some of the top people that were on a lot of our games in the past, so we've got a very seasoned group of developers who have been able to produce quite a few massive multiplayer online games, and part-and-parcel of the loot is the ability for our players to actually craft and create.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

RG: We mean more than just crafting a sword, or the generic crafting systems. There have been games saying we are going to be doing a heavy push into player-created content, though I think most player-created content in most games is not good. A lot of games that have done player-created content on the main map of the main world end up being a bunch of unfinished or not well-finished content that a player has to walk through and pass in order to reach the brief moments of great content that either the professional creators put in, or the handful of really good creators put in an interesting juxtaposition.

The one out of 1000 creators that are really great find economic reward for being such a good creator. So what we're going to do is try to take the model of really rewarding creators [like in Minecraft or Roblox] but put it into an MMO setting where the main world is a fully traditional MMO setting. But as soon as you go into a room, the world itself is sort of the hub to these more individually crafted spaces, many of which we will create with our own team, but we'll be very happy to be competed against or beaten by individual creators. So we think that's a big new piece that I believe will bring to us both famous and unknown creators who will play alongside us, and make money independently of us.

What's going to make this stand out from the MMO scene now?

TP: When you think about the kind of the landscape of MMOs, the last major one was New World, maybe Lost Ark if you call that an MMO. Obviously Ultima Online is kind of like a foundational MMO, a lot of what comes after it kind of follows directly out of it: they don't pick up some of the best stuff if you ask me. There's Everquest, all leading into WoW, and ever since it seems to me they've been kind of on more-or-less the same track. It seems like a genre that's very, not in a rut, just a groove.

RG: Let me describe something I think Ultima had originally, there was both good and bad. However, it lost the good over time, I would argue, and maybe got rid of some of the bad. We started with Ultima Online as a true Wild West free-for-all. And while the towns were supposed to be safe and you couldn't gank each other literally within the walls of a city, the outdoors were by plan the Wild West and you could chase each other down. From an edge cases standpoint, which we thought was kind of funny to observe, but not if you're the person who's the victim, somebody would entice you to come outside and they'll protect you—and as soon as you're outside they kill you. Somebody found a way to put a teleporter just inside of a bank to where, when the roof popped off, you step into the teleporter, you're in the open world, and killed.

Even without those edge cases, just feeling like there's no way to participate in the game without being forced to run the PvP gauntlet that anyone who was not super experienced was likely to lose. That on the one hand made it for those PvP players super exciting and fun: but actually limited dramatically the number of players that ultimately came into the early Ultima Online, and we ended up having sort of this bifurcation of the predator class thinking this is the very best game they could possibly imagine, and we as a company struggling to get new players in enough safety corridors to rise far enough to be willing to play, versus just give up because it's not fun to be the prey.

And the way we tried to solve that with Ultima Online because it was operating in real time, is we set up the model of safe server travel and Felucca, the dangerous server, and that did actually technically solve the problem. But it also sort of threw out the baby with the bathwater in my mind, in that it actually never really satisfied the story people. They go into a completely non-dangerous environment, but you kind of want a little bit of an edge to make you feel alive. And you took all the prey out of the predator environment, which makes the predator environment no fun either. It was at least an attempt at a solution.

We're now in a time where technology's evolved quite a bit, and I think we can go back to something more akin to the original Ultima Online, which is that there are large swathes of the game which in fact are hazardous, that there is no good motivating reasons to go into those places that are hazardous for reward. But you always know when you are migrating out of the zone of safety, not because of some arbitrary law and the perimeter of the city. Because the rules are so fundamentally changing, those spaces are built-out in a way that… I think we can entice people across the boundaries, versus make it unsafe to get from my friend's house to your house. And therefore we can bridge that gap.

TP: We're definitely going to have a situation where players can actually own the dungeons, and set them up and stock them with creatures. And there can actually be players that are just miners, and I talk a lot about the fact that we want to make sure that when you travel with a party, that puzzles have to be overcome with multiple uses of your party skill sets—this is not just hack the crap out of somebody, you know. You see in more modern Gloomhaven a great example of a very innovative role playing system, where every player has his specific skill set, and you need them all to overcome the puzzle and overcome the challenge.

Can you explain the blockchain element in Effigy?

TP: My great uncle was Chet Atkins. And he gave me a guitar, and having to try to prove that that was actually his first guitar was really difficult because I didn't have any kind of records to do that. So I've always looked at this as an interesting part of the spec. And when they started introducing NFTs I was like, you know, this is pretty interesting, and what if we could do something different? What if Richard and I could take a whole community along with the journey of actually creating a new game, a new quote-unquote Ultima? And what if the people who did this actually really own stuff that they could actually make money on. So they're not just players, they could also be investors and reap some rewards from that. So our first kind of conversations were less focused on the blockchain side of it and more focused on how can we leverage the NFTs to really make a game have true assets for people.

RG: You're noticing we're both giving you lots of caveats. And I want to throw in some more too, which is, on the one hand, I've been an investor in Bitcoin and Etherium and a few other tokens for a couple of decades now, and believe very much in digital currency. That being said, I also think that a lot of the gaming that is being built on either blockchain or with NFTs or with a cryptocurrency as its underpinning currency are flights of fancy.

My case for it goes like the following. When we go back to arguably the first MMO, Ultima Online, and the limited edition digital objects that began to sell on the early version of eBay, you know a little house or a sword would sell for thousands of dollars. A blacksmith shop in the centre of a major city, almost instantaneously, would sell for $10,000 on eBay. And we would look at that going like, 'oh my gosh, what does this mean? Do we stop this? Do we support it? You know, how do we really feel about this?' Because we had never made a banking-level protection of the transfers: if the game had a hiccup, or a rollback, you know, people could have paid real money for something that disappeared. We were supporting entertainment, not transactions of supposedly digital objects.

If you fast-forward to now, a lot of people are thinking that if I buy my virtual sword, and it's really mine, I can therefore take it outside of my wallet and put it in some other game. There is no other game we're going to take these things into. A game's components or pieces really are directly appropriate to that game, it's hard at least for me to imagine any transitory value outside of the game. Instead, like Todd was saying this has the provenance of knowing where this came from, its full history.

But it also includes things like, if you look at the way we had community support join us with Shroud of the Avatar as a case point: we started on Kickstarter to raise some money, we moved to seed investment to raise some more money, once the game was far enough along we began to sell digital assets or property within the game. And that created this sort of mishmash of all these different ways that players participated in helping to create and be a part of that early community. And that mishmash is very hard to manage, because people have wildly different expectations, depending on which of those phases they came in through. And so the nice thing about this method is that it's a kind of a one-stop shop, of how you're engaging your community that starts before the game exists and runs through the operation of the game.

The audience perception of NFTs and blockchain tech in games is not good. People don't like these things, they don't see what they add to games, and it is a space where there seem to be a lot of dodgy dealings.

RG: What we're trying to do is, we're not trying to drive people into becoming blockchain aficionados in any way. We do believe, however, that by storing some of this information on the blockchain, by getting rid of all the other fundraising mechanics, we will add our own front ends to those to make it as easy as any other normal thing, we're just going to keep the data ourselves on the blockchain. And by the way, if you ever do want to put it in your own wallet, because you are a crypto native person that's decided that you think that's a fun thing for you to do, you can, but otherwise we're going to hold those things off for you. And so this will be transparent to the players, the fact that we are using blockchain as one of the pieces of the background of the database.

TP: Gabe Newell, if you read what he said on this, I tend to agree with him that there's a lot of dodgy players. Unfortunately I also feel that way about microtransactions, I feel that way about a lot of the things that you're seeing out there in terms of different things that go on in the gaming world. I do think there's bad actors across the whole spectrum, even back in our day when we were selling games in plastic bags. And I think that what Gabe says which is true is there really isn't any good example of a good NFT-based game. So for us, NFT becomes a sub-part of what we're trying to do.

There's going to be those people who want to get involved at that level, and want to own a piece of land or a building, they're going to want to customise that, they're going to want that to have real value. And what NFT delivers to them is the ability to sell that thing with value. That's really all we look at when we think about NFTs, provenance alone, this is kind of a closed ecosystem.

RG: I mean, we could come up with 'don't call it an NFT call it RFT,' call it anything you want to, we've come up with a system whereby when you put money in you have the opportunity to get money out. We're certainly doing more for players than just, when they put their money down, they play the game and all they're getting out of it is 60 hours of fun.

Look, I see all the negative things about artists being screwed when they register their NFTs, and then it gets sold, and they don't get anything on the back end for that. This isn't that kind of a play. I mean, there's really no value in these objects, except within this ecosystem. And, you know, perhaps somebody will buy land and then turn around and try to sell that land at a higher price. Well, that's a normal environment.

Players have certain expectations of a Lord British game—will they be met?

RG: I would argue that one of the things that's been nice about the journey I've been on as Lord British is that the sense people have from Ultima is an expectation now that my games will have a set of ethics and moral code underpinning it. And in fact we were talking in our game design sessions earlier today about how much of the world [should require] players and designers to bend to the Lord British truth, love and courage principles? And should there be play spaces that allow people to experiment with things that are completely unrelated: dark and evil torture lands, because they think it's fun?

To my mind we're going to set up a backbone that ties together all of these regions that are the, you know, The Rules According to Lord British, but the further away you get, the further into the Outlands you go, the more you'll be able to bend those rules and find forms of play that are… unrelated, shall we say?

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."

Most Popular