Reinstall invites you to join us in revisiting classics of PC gaming days gone by. This week, Paul returns to the ambitious Doom-era FPS/RPG hybrid, Strife.

Strife did Deus Ex before Deus Ex – sort of. Released in 1996 and powered by id's Doom engine, it didn't manage to pull off that same fusion of roleplaying elements, stealth and freedom of choice that made Deus Ex great a few years later, but it certainly took one of the first stabs at it, and 17 years after its release it still does a pretty fine job.

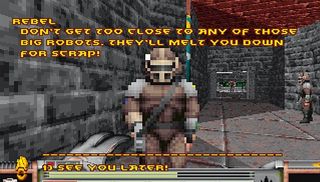

Strife was one of the first games to take an engine used by first- person shooters and to bolt all kinds of extras onto it, showing that it could be used for far more than just blasting away at monsters. It's a Doom-a-like set in a hub-based persistent world where you can talk to just about anyone, albeit through terrible, cheesy voice acting. It's an ambitious last hurrah for the Doom engine, following more simplistic games such as Heretic and Hexen, and it wears that heritage proudly: you get to do a lot of shooting with a lot of novel weaponry. And people explode.

The game marries science fiction and the medieval, putting you in a world of peasants and power armour, taverns and teleporters. It's a world that has fallen victim to a terrible virus and then been subjugated by a mysterious Order, a strange religious organisation that took power when everything went to hell. You're the one fighting to restore freedom with a crossbow and rocket launcher.

Coming back to Strife is a delight. The hub that sits at the centre of the game is a town within the iron grip of the Order. Armed and armoured guards are posted on every corner, just waiting to strike should you decide the best way to rebel is to fight in the streets.

You're better off hanging out in the tavern, seeing if you can pick up any jobs and buying equipment for the missions ahead. It's not long before you'll find the nearby headquarters of the resistance, and they'll start both training you and plugging stamina implants into your body to beef you up.

Your missions will have you trotting off across the hub to various new levels, each of which is impressive in both its size and its complexity, especially considering that the Doom engine couldn't model rooms above or below other rooms. You visit a sprawling warehouse, the frustratingly complex sewer system and the Order's castle. The latter you'll find yourself assaulting with a detachment of comrades.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

None of these areas are particularly pretty and the years haven't been kind to Strife's grey corridors, but the game's mixture of the historical and high-tech is distinctive. Deep in the bowels of a mighty citadel you'll find huge computer screens mounted across the stone walls, while the private quarters next door might boast no more than candles and a four-poster bed. It serves to give the locations you visit variety: that castle you assault is fortified by both force fields and thick stone walls.

Many of these levels have secrets and alarm systems, and while Strife is a game that's very much about shooting, it's possible to stealth or part-stealth these levels, creeping through them with a crossbow loaded with poison-tipped bolts. Many mission briefings encourage playing this way, but it's almost inevitable that things are going to get noisy sooner or later.

When combat does break out, it's not as fast or fluid as Doom, though it does still feel very similar. What it lacks in speed it makes up for in its interesting selection of weapons: as well as the usual rocket launcher and assault rifle, there's a flamethrower, improvised mines and one of gaming's earliest grenade launchers.

Strife is similarly basic in its introduction of roleplaying elements. You can talk with almost anyone, but your conversation choices are very limited, while character improvement is restricted to a few very rudimentary advancements such as improving your weapon accuracy or gaining ten more hit points. There are, however, multiple endings, depending upon the order that you complete certain tasks in, or if you fail outright.

What made Strife great was how many ideas it introduced to what at the time was a pretty simple formula. It was always providing something new to see or play with. There's the infiltration mission where you're in disguise, the teleporter tool that beams your allies to your position, and the Sigil superweapon, assembled in five stages and more powerful with each addition.

Then there's the horrible, tempting Chalice mission, a quest to steal one of the Order's prized possessions. It's a set-up, an attempt by your enemies to bait and kill you that you're offered at the very start of the game. If you try it then, you're doomed to failure, but later on, once you're souped up and much savvier, it's a much easier proposition. That's just one example of Strife trying its best to be non-linear, and it prefigures the sort of thing Dark Souls gets lauded for today. Just because you can try something right now, that doesn't mean you should.

Strife is still an interesting game with an unusual premise and a lot to show. It's not a great shooter, a great RPG or a great stealth game, but it does an admirable job of wearing each hat it tries on. If it had been released a few months earlier, it might have been a success.

Sadly, it wasn't the cutest kid to graduate in the class of 1996. Its engine was already eclipsed by the shinier, show-off interactivity of Duke Nukem 3D, and Quake was only weeks away. Many gamers may simply have assumed it was just another second-rate texture-mapped shooter, of which there were an unholy number at time. It's not.

Strife is worth remembering today for offering an early open world, and for the variety of ideas it smooshes into it. It certainly doesn't deserve to languish in obscurity. Given that it's now abandonware, there's no reason for you not to give it the attention it never received in its day.

Most Popular