The evolution of The Elder Scrolls

How The Elder Scrolls series went from gladiators to Dragonborn.

There’s a theory that no one ever loves one of Bethesda’s open-world games as much as they love their first. Whichever Elder Scrolls you first lost yourself in will be the one that sticks with you forever, the theory goes, and none of the others will measure up. But although there certainly is a format shared by all the single-player RPGs in the Elder Scrolls series, there isn’t a formula—each new game makes significant changes, and many of those changes seem like responses to common criticisms of the previous fantasy epic.

It feels like Bethesda pays attention to the things people complain about and use mods to fix, though the company rarely gets credit for it. It’s especially noticeable when you put all five central games in the series—ignoring the spin-offs—side by side to see how they’ve evolved, and how different they are. This is our history of The Elder Scrolls, from Arena to Skyrim.

The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994)

Speaking of evolution, The Elder Scrolls: Arena went through some famously massive changes even before it was properly begun. Initially conceived as a game about a team of gladiators competing in turn-based battles (hence the subtitle), what started as a series of sidequests in dungeons and cities took over during early development and became the core of the game, reshaping it into a first-person real-time RPG in the mold of Ultima Underworld.

What Arena added to the genre was a massive overworld. Its scale still hasn’t been matched by any of the follow-ups in the series: players can travel across the entire continent of Tamriel, including the main locations of each of the later games. It isn’t like the continuous open worlds of today, though. Fast travel is the only way to get from one settlement to the next because the wilderness is algorithmically generated filler surrounding each town. You can walk down roads looking at trees and stumbling across the occasional dungeon for hours, or at least until the game’s memory fills and it became unstable, but you’ll never reach the next town.

In those towns the people are created by a similar algorithmic process. Each character has an individual name and career, but every butcher tells you about the same shipment of mutton and every second joiner complains about dryrot. Each place feels like a remix of the last, the random name generator throwing up forgettable shops like “The Basic Merchandise” with the same white-skinned human character models for bartenders and other service providers no matter which race of people the rest of the populace in that area is composed of. There are sidequests in these population centers, picked up in bars, but all are variations on walking around town to collect or deliver things.

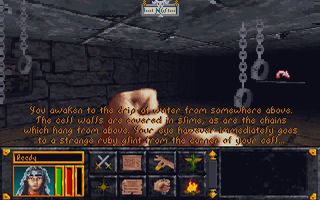

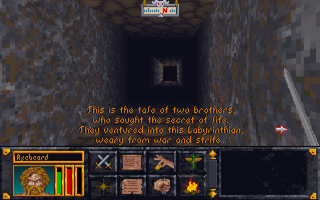

Where Arena shined was in its main quests. Not for their bare bones story—after escaping from a prison you’d been locked in by an evil wizard who banished the Emperor to another dimension, you were sent to collect the pieces of a magic artifact to defeat him—but for the dungeons each chapter is set in. They’re hand-crafted, making them far more atmospheric than the randomized dungeons in the rest of the game, and each has a dramatically different theme. In Selene’s Web spiders are bred in pits and signs warn their trainers to be careful, while in Labyrinthian (revisited in Skyrim) the story of two brothers cursed to guard the place is written on the walls.

Most of the dungeons have an alternate way of exploring them that monsters won’t use, perhaps by jumping into mineshafts or underground rivers, as if the player is an alien in the ventilation shafts leaping out to launch surprise attacks before scurrying away. And though its sound palette was limited, the roar of a troll in the distance or the beating of drums in the deep adds menace.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

The rest of the world isn’t so atmospheric, and not just because of the randomization. Tamriel then was a much more generic fantasy setting. Its Orcs are typical dungeon fodder rather than a playable race, and the Khajiit are described as “feline and sleek” but look like ordinary humans. There are no Daedra and no Dark Brotherhood assassins. Though the Elder Scrolls themselves are referred to throughout Arena, repeatedly looked to for clues to the location of the next dungeon, a lot of what we think of as essential parts of the Elder Scrolls series aren’t present, and wouldn’t appear till its sequel.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.

The Elder Scrolls Online dev says the 'metaverse' is sinking because it ignored 20 years of games doing the exact same thing: 'It's not new, and they should stop treating it like it's new'

The Elder Scrolls Online has made nearly $2 billion in its lifetime, 9 years after the big comeback that doubled its player count overnight

Most Popular