Revisiting Deus Ex: Invisible War, one of PC gaming's biggest disappointments

As a new Deus Ex sequel arrives, we look back at the failed ambition of 2003's Deus Ex 2.

The Statue of Liberty doesn’t play a huge role in either Deus Ex or its sequel, but I’ve still come to think of it as the symbol of those games. It book-ends the series-as-was, prior to Human Revolution. The first mission of Deus Ex, the last mission of Invisible War. In the first game, it’s a symbol of ambition: one of the largest and most intricate game spaces designed up to that point, full of secrets and ways to chart your own path.

In Invisible War, it’s more a sign of submission, where the sequel’s many concessions to the original Xbox hardware are all on display. The inferior aesthetics that make every location look the same. The map split into chunks because the system can't keep it all in memory. The once natural choices now stated outright, blunt and simplified. Everything that the original map did so well, its return trip fails miserably to match. Such is the risk of following up one of the best games ever made.

Looking back all these years later, the question isn’t whether or not Invisible War was a better game than Deus Ex, because the answer is a flat no. It just isn’t. Coming second to one of the greatest games of all time would hardly be a shame, though. Now that the disappointment has faded, and a new incarnation of Deus Ex has gotten its own sequel, is it time to re-evaluate Invisible War for what it is, rather than what we hoped for 13 years ago?

It’d be great if the answer was yes, but replaying it now, Invisible War has aged about as poorly as a game can. Much of this is, again, the result of having been designed for the original Xbox, though the bland futuristic setting and inferior writing somehow make it feel like both the big budget sequel and cheap straight-to-video knock-off of the first game.

The 20XX files

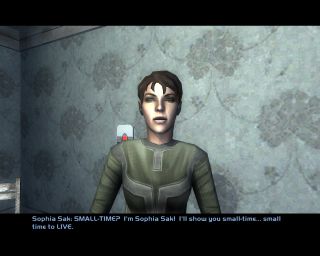

Invisible War raises the stakes by going 20 years further into the future and tries to drive more of the story through characters and relationships, but it never quite manages to land the quantum leap or compensate for the issues those choices introduce. Invisible War’s hub areas are poorly conceived locations, tiny and bereft of detail. Easily the worst is the Cairo Arcology, home to the great and good, which feels like it’s modeled after an airport departures lounge and features an open recruiting booth for the Knights Templar. It’s explained that they’re simply advertising where the people they want to recruit are, but its conspicuous placement still feels a world away from Deus Ex’s gritty conspiracy theories.

The frustration is that Invisible War isn’t a lazy sequel by any stretch. It’s desperate to reinvent both itself and the series, and to find the next big leap. It tries so hard from the very first moment, an awesome intro that sees the entirety of Chicago wiped out by a nanite weapon. It goes out of its way to offer more choices on its main path than Deus Ex, with multiple factions to work for at any point instead of a forced transition from government yes-man to rebel agent.

This time, we’re not dealing with goodies and baddies, but distinct groups with their own agendas: the World Trade Organisation, religious group The Order, and the awkwardly named ApostleCorp, run by Deus Ex hero JC Denton. The missions only offer slight variants, like killing a scientist or stealing his gun, but it’s enough.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

Invisible War tries, but its reinvention just doesn't work. It’s not all because of the technology, though that certainly doesn’t help. The missions are too short due to the tiny map sizes, and the world both too futuristic to resonate and too far beyond the engine’s capabilities to properly depict. Seattle, for instance, is a two-tiered city connected by an ‘inclinator’, but forget any picturesque views while travelling. It’s an interior location that, like much of the game, looks like a succession of slum and warehouses, slightly melted into metallic blue and grey.

Invisible War could be forgiven its technical shortcomings, but they're just the start of its problems. The deeper issues are rooted in its basic design. The faction system, for instance, spends most of the game bouncing between being comical and just plain broken.

Seattle looks like a succession of slum and warehouses, slightly melted into metallic blue and grey.

Wander into an apartment block, the Emerald Suites, and the head of the WTO—a complete stranger at this point—phones up to ask if you’d mind raiding the Minister of Culture’s bedroom. The intro starts with you under attack by the religious faction, nominally to ‘rescued’ from a fate as a test-subject for the not-particularly-scary Tarsus Academy, only instead the leader of the assault has decided to kill everybody. Yet despite this, the Order can’t get it into its head that, just maybe, you might hold something of a grudge. Instead, for the rest of the game, they’re constantly in your head as if you directly work for them.

This reaches a head in Cairo. If you choose to ignore the Order and choose to instead kill the plants in a greenhouse on behalf of the WTO, they actively send a couple of agents after you. Kill them, and the Order respond with, more or less “Now you see what happens to our enemies. Unrelated, got another assignment for you if you’re up for it. Hello? Hello?”

Imperceptible war

This isn’t just cherry-picking a couple of silly moments. The whole sweep of Invisible War is basically like this, with none of Deus Ex’s focus or sense of danger to pave over the silliness. Even the element of freedom is badly affected by the small levels and minimal payoff for taking different paths and approaches. The story is terrible, most characters completely forgettable despite its best efforts to give them depth. The ridiculous, apocalyptic scale of the endings goes far beyond anything that the game has earned up to that point.

Yet ironically, when Invisible War steps back from the big picture to sweat the small stuff, it’s often surprisingly effective. Its subplots are far better than anything in the main story: the mystery of AI helicopter pilot Eva, the way that each faction is represented and given an enthusiastic face by one of your fellow Tarsus students, or the feud between rival coffee shops Pequod’s and Queequeg’s, which turns out to be a mirror of the real global situation (false competition, with the Illuminati secretly owning and puppet-mastering both the WTO and the Order).

And yes, as everyone who played Invisible War has been waiting for, there’s the genius of NG Resonance. This virtual pop-star, knowledge broker and not-very-subtle government informant (played by the singer from the band Kidneythieves, whose music appears throughout) is easily one of the best inventions in the game, being a case where humanity and technology are allowed to combine to create something interesting. Sinister, yet friendly. Futuristic, yet approachable. It’s no wonder that when Invisible War is brought up, NG is almost inevitably the first fond memory.

The other futuristic changes proved more controversial. To its credit, Invisible War wasn’t afraid to change things up. Its biggest innovation though, universal ammo, really didn’t work. The idea is that rather than having dedicated bullet ammo and rocket ammo, you have an ammo pool. A bullet uses up a mere blip. A rocket uses up a ton. The idea was to expand on player freedom by ensuring that all their tools would be available at all times.

In theory, it’s a great idea. The catch is that it was so easy to waste your shots, especially not knowing when the next refill would be, that it often left you without any of them. Worse, even if you played carefully, it was impossible to play tactically without any real idea of when the next ammo stash would be. At least with conventional ammo you can be fairly sure that more bullets will be along soon, but it’s probably best not to waste a precious rocket.

Some people loved this system. Overall, though, the implementation was judged a failure, and not a model that future games opted to bring back for further exploration. It was, however, the kind of innovation that helped Invisible War’s reputation over the years as a game that at least attempted to break new ground and take Deus Ex forwards as a series, instead of just assuming its problems were solved. It certainly wasn’t a lazy, coughed-up sequel designed to make a quick buck, or one that lacked for talent behind the scenes.

Instead, it was the victim of technology that wasn’t ready, and a team that hadn’t quite grasped the spirit of Deus Ex—team leader Harvey Smith later confessed to having taken it too far out of the familiar, and relying on the advice of hardcore players and fellow designers about what was wrong with the original game, rather than leaning on players who loved the original to hear what it did right. (Smith would of course later more than make up for this with Dishonored, which despite being overtly mission based rather than offering a continuous Deus Ex style flow in sprawling social hubs, is as close to being a Deus Ex successor as anything that officially bears its name.)

The future, yesterday

And what of the other argument, that while it fails as a Deus Ex game, Invisible War is still a solid RPG on its own terms? Sadly, going back really doesn’t convey that. It’s not an awful game, but even if you forgive its technical faults (and it really doesn’t run that well even today), it’s a stodgy, lifeless, uncharismatic adventure. Invisible War got its reputation as a decent RPG because in 2003 and much of 2004, the demand “Well, show me a better Deus Ex style game” could only be answered with “Well, there isn’t one.”

This wasn’t, however, because there were inferior attempts, but because Deus Ex and Invisible War stood alone.

Today the most obvious comparison is Vampire: The Masquerade: Bloodlines, from less than a year later. It’s a game that holds up despite itself most of the time, and not even that at the end. As clunky as it is, Bloodlines’ setting, its characters, its choices and its general vibe help obscure the kinds of flaws that shine bright in Invisible War.

Much like fellow disappointing sequel Thief III (minus the Cradle and a couple of other good bits), Deus Ex: Invisible War is a game that sits in a bubble as the result of its time’s weaknesses rather than strengths. It’d be great to think of it as a lost classic, but even at its best, the kindest compliment is: “It tried.”

FF14 and FF16 senior translator Koji Fox says 'you can kinda tell' game director Naoki Yoshida is 'like: I'm done with dark fantasy, I want to do something light again'

Baldur's Gate 3 player summons roughly 88 minions to conquer Honour Mode with a glorious army of spore zombies, elementals, and Scratch the best boy