By Joe Skrebels

There’s something pleasingly human about people looking for new ways for machines to help them. That primal cocktail of curiosity, ingenuity and, yes, laziness has spurred on practically every technological advancement since that first ape threw a rock at a deer and realised it was fun.

If you’ll allow me to get recklessly bigheaded this early on in the article, #procjam, the game jam with the tagline ‘make something that makes something’, could represent the beginning of the next evolutionary stage in that thinking. Because at #procjam, people aren’t just making things to help us any more, they’re making things to make things that help us.

In this case, those things are procedural generation algorithms that spawn, in the words of Michael Cook, jam organiser, “games, tools, art stuff, toys or Twitter bots.” Cook is also a computational creativity scientist the and creator of the beguiling yet terrifying game-making AI Angelina.

Hello Games’ Hazel McKendrick discussed how No Man’s Sky is replacing whole elements of traditional design with generators.

The brief is an unusually broad one for the often constrictive world of game jams—and that’s very much the point. “Often, jams have very tight time constraints or don’t let you use any existing code,” Cook explains. “But I wanted to use this more for the purposes of catalysing exciting work, so I’ve said yeah, use existing code if you want, work in teams, and if you need an extra day take an extra day.”

That more open approach applied to the organisation of the event as a whole. Cook opened the two-week development period with a day of theoretical and practical talks from procedural generation experts, intended to introduce the attendees to the concept of procedural generation, and to offer ideas to jammers. Among others, Hello Games’ Hazel McKendrick discussed how No Man’s Sky is replacing whole elements of traditional design with generators, developer Mark Johnson explained how his in- progress giga-roguelike, Ultima Ratio Regum, can generate everything from entire world religions down to leaf placement on a single elm tree in under three minutes, and Northwestern University lecturer Dr Gillian Smith described in intimidating detail how procedural generation is, essentially, the birth of a real-life Holodeck.

If those talks sound enthusiastic to the point of fantasy, it’s probably because Cook selected those speakers, and the jam’s organiser is gleefully open about his dreams for procedural generation as a cornerstone of game design.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

“One of the questions that we want to look at with procedural generation in the future is ‘can the system try and surprise you intentionally? Can it innovate?’ Those are exciting questions, and they start pointing not only to new games but new concepts of what a game is. They’re as fundamental an invention as something like mouselook. I just hope that at the end of the jam, you’ll be able to sit down and look at all these broken experiments—because a lot of them will be broken—and be like, ‘you know what, if we went away and spent a year on one of these things, we would have something that no one’s ever done before.’”

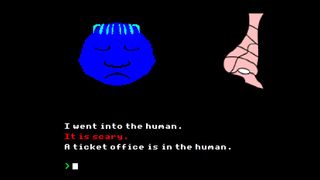

So what of those experiments? Given the moon-eyed wonder at the possibility of it all, what did the world’s assembled nerds conspire to create in those two weeks? Perhaps more importantly, what did those creations create? I’d draw your attention first to Tom Coxon’s Dreamer of Electric Sheep—a BBC Micro-style text adventure that performs so many simultaneous calculations it would make an actual BBC Micro burst into flames. Beginning with a blue, sleeping face and an introduction to a location, Dreamer looks fairly low- rent—until you realise every piece of description it provides is being scraped from an online semantic association resource built to power AIs. Its responses are all a little off , which provides the perfect, menacing atmosphere for a dream. I left a nightclub, then found myself in a fungus-infested forest before accidentally creating a human who attacked me until I jumped inside him to hide in a ticket booth. I’m pretty sure The Mighty Boosh used to write episodes this way.

At the other end of the spectrum, DragonXVI’s The Inquisitor is a fully- fledged, self-contained piece, presenting you with a new murder mystery every time you play, complete with locations, cast, motives and weaponry. The sheer number of moving parts means you’ll need to draw maps, make notes and put on your smartest thinking cap. It’s like Cluedo as created by Nabokov and I can’t quite believe it was made so quickly. I’m rather expecting a Kickstarter to pop up soon. Then there’s the minimalist roguelike, JET/L AG , which borrows from Hotline Miami , a maze game with duplicitous robots, and Nauticalith , which is more or less a terrifically bleak, endless take on The Wind Waker ’s sailing sections.

And there are those tools and oddities Cook mentioned. The jam has spawned tile drawers, planet generators, any number of Civ -style world map builders, a monster sprite maker, a complex little tool for making in-game fabric (which is already being used in another #procjam game) and even a Pokémon spawner. One cleverdick made a printable, procedural board game, DUNGEN [star], another a ‘relaxing bonsai experience’. There’s also a metric tonne of procedural first-person shooters, slightly cheaply taking advantage of the fact that 7DFPS (the jam that once spawned the wonderful SuperHot) was running at around the same time.

But the goal has been met. Here are tens of things that make things, of all kinds. And it needn’t end there—as Cook tells me, “next year, I’m thinking of having an optional bonus objective where your entry for next year has to use an entry from this year.” Essentially, use a thing that makes a thing to make a new thing that makes things.

#procjam is here to stay, and it’s building itself. Appropriate, really.

Hey folks, beloved mascot Coconut Monkey here representing the collective PC Gamer editorial team, who worked together to write this article! PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.

Most Popular