Most PC hardware pricing is back to normal so why not GPUs?

Prices are tumbling, except for graphics.

A high quality 1TB can be had for under $100, Crucial will sell you a 32GB DDR5 kit for about the same money, we just reviewed an excellent 27-inch 1440p 165Hz panel that goes for $250, Intel's Core i5 13400F can be had for just over $200 and motherboards for AMD's latest Ryzen 7000 CPUs just hit $85.

But graphics cards? They're the one component class that hasn't gone back to normal. What with the weirdness of the pandemic and then war in Ukraine, the prices of almost everything was out of whack for a while. But now many if not most classes of PC hardware are trending back towards what you might call normal pricing.

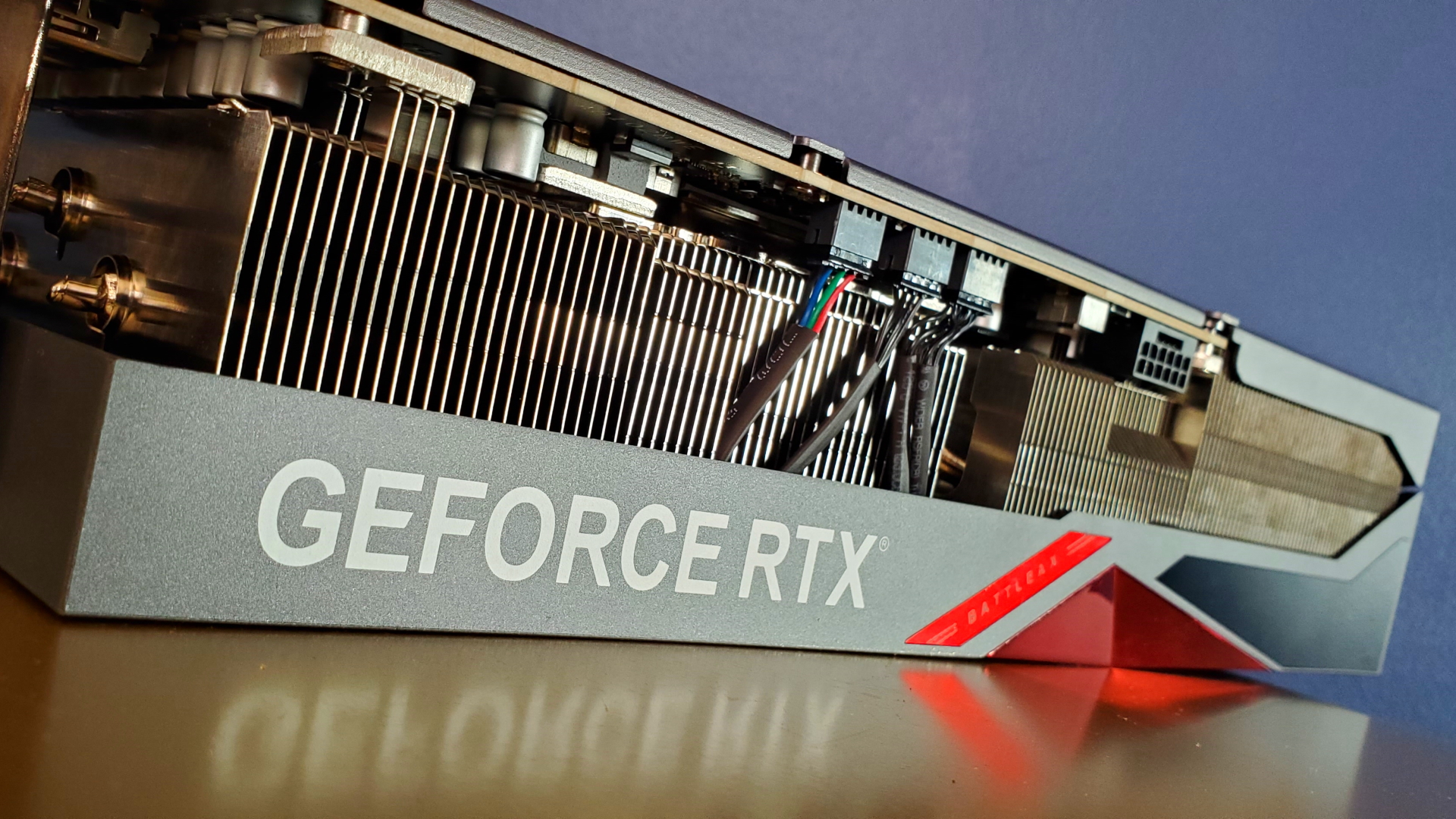

But not GPUs. Oh no. The cheapest of Nvidia's new RTX 40-series right now is the $799 RTX 4070 Ti. Just a generation ago, the MSRP of the RTX 3080 from a tier above was $699. And the 3080 itself looked pricey at launch, even if the combined impact of a crypto craze and the pandemic saw street prices at multiples of that.

So what, exactly, gives? One of the popular arguments for toppy GPU pricing involves wafer costs from TSMC. That's the Taiwanese foundry that makes all of AMD's GPUs and also manufactures the Nvidia RTX 40-series (Nvidia went with Samsung for the RTX 30-series family).

Anyway, we'll never know for sure what anybody pays TSMC to make their chips because such contracts are closely guarded commercial secrets. But here's what we can say. If TSMC's wafers are now so expensive, why did the RTX 4090 only increase by $100 over the RTX 3090?

The RTX 4090 is by far the biggest and most expensive chip in the RTX 40-series. It will have by far the worse manufacturing yields on account of its size and if wafer costs have gone up, it will have been hit hardest. But when you consider that the MSRP of the RTX 3090 was $1,499, the RTX 4090 pricing hasn't even kept up with inflation.

Meanwhile, the RTX 4080 leapt to $1,199 from the $699 MSRP of the RTX 3080, despite stepping back from using Nvidia's biggest GPU, which is what you got with the RTX 3080, to its second tier chip.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Then there's the example of laptop pricing. Already, laptops with the new RTX 4060 mobile GPU can be had for a little over $1,000 and thus cost no more than RTX 3060 laptops when they first appeared. Do TSMC wafer costs only somehow apply to desktop GPUs? Hardly.

So, this can't all be about wafer costs. There's something else going on. And only Nvidia and AMD knows exactly what. To be clear, AMD's GPUs are no exception to all this. The cheapest of its new Radeon RX 7000-series cards has an MSRP of $899, though a lack of demand has already pushed street prices below that mark.

But hang on, can't you get an AMD RX 6700 XT for $350? Isn't that a good deal? It's a great deal by current standards. But $350 for what is something like a sixth tier card in performance terms that's over two years old and uses a last-gen architecture is not a good deal in historical terms.

Speaking of demand for AMD's $899 RX 7900 XT, that's the real oddity. GPU demand like demand for pretty much all PC hardware is cratering right now. And yet GPU pricing remains miles above historical highs, even accounting for inflation.

In practice, one can only speculate. But one plausible scenario is a concerted effort to push GPUs upmarket. Relative to CPUs, GPUs remain relatively specialist in terms of the user base. Not everyone even needs a discrete GPU in their computer.

At the same time, the barriers to entry for anyone fancying the idea of getting in on the market are huge. So, it's not like anyone can just slide into making GPUs and undercut AMD and Nvidia. Even Intel with its huge resource and unique experience in PC hardware is struggling to be competitive at the mid- and high-end with its new Arc graphics.

Another related factor is the burgeoning AI industry. GPUs in data centres were already becoming more important, but with these new AI language models, GPUs have suddenly taken on a whole new significance.

OK, ChatGPT doesn't run on gaming GPUs. But the perceived value of GPUs and demand for that chip type is currently exploding. And that's bound to pull gaming chips along for the ride to at least some extent.

Indeed, gaming GPUs look like a bit of a sideshow next to the money Nvidia seems set to make from selling GPUs for AI training. So, Nvidia will still sell you a gaming graphics card. But it's a lot less worried about whether you think it's good value than back when pretty much all its revenue came from gamers.

AMD isn't nearly as big as Nvidia in the AI industry. But it is seemingly being dragged along all the same. As the smaller player, it makes far fewer GPUs than Nvidia. It could decide to undercut Nvidia, but history suggests it probably wouldn't sell that many more cards, such is Nvidia's dominance of PC graphics mindshare. So why bother?

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest

The one possible joker in this very stacked deck of cards is Intel's aforementioned Arc graphics. The latest rumours suggest Intel's next gen Battlemage GPU could arrive next year with performance on a par with an RTX 4070 Ti or even RTX 4080.

That's a lot of gaming performance and, if it's priced right, Battlemage could make a big impact. There's certainly an argument for Intel pricing Battlemage a bit lower than the competition. After all, if it performs like an RTX 4070 Ti and costs about the same, why would any gamer take the risk?

So, if Intel comes in a little under Nvidia and AMD, that could be just what the market needs to bring some sanity back to the graphics market. In the meantime, all we can do is hope.

Jeremy has been writing about technology and PCs since the 90nm Netburst era (Google it!) and enjoys nothing more than a serious dissertation on the finer points of monitor input lag and overshoot followed by a forensic examination of advanced lithography. Or maybe he just likes machines that go “ping!” He also has a thing for tennis and cars.