Starfield's over-reliance on fast travel makes it feel tiny, but it's just part of a larger problem

You can visit new star systems at the touch of a button, but exploration takes a backseat.

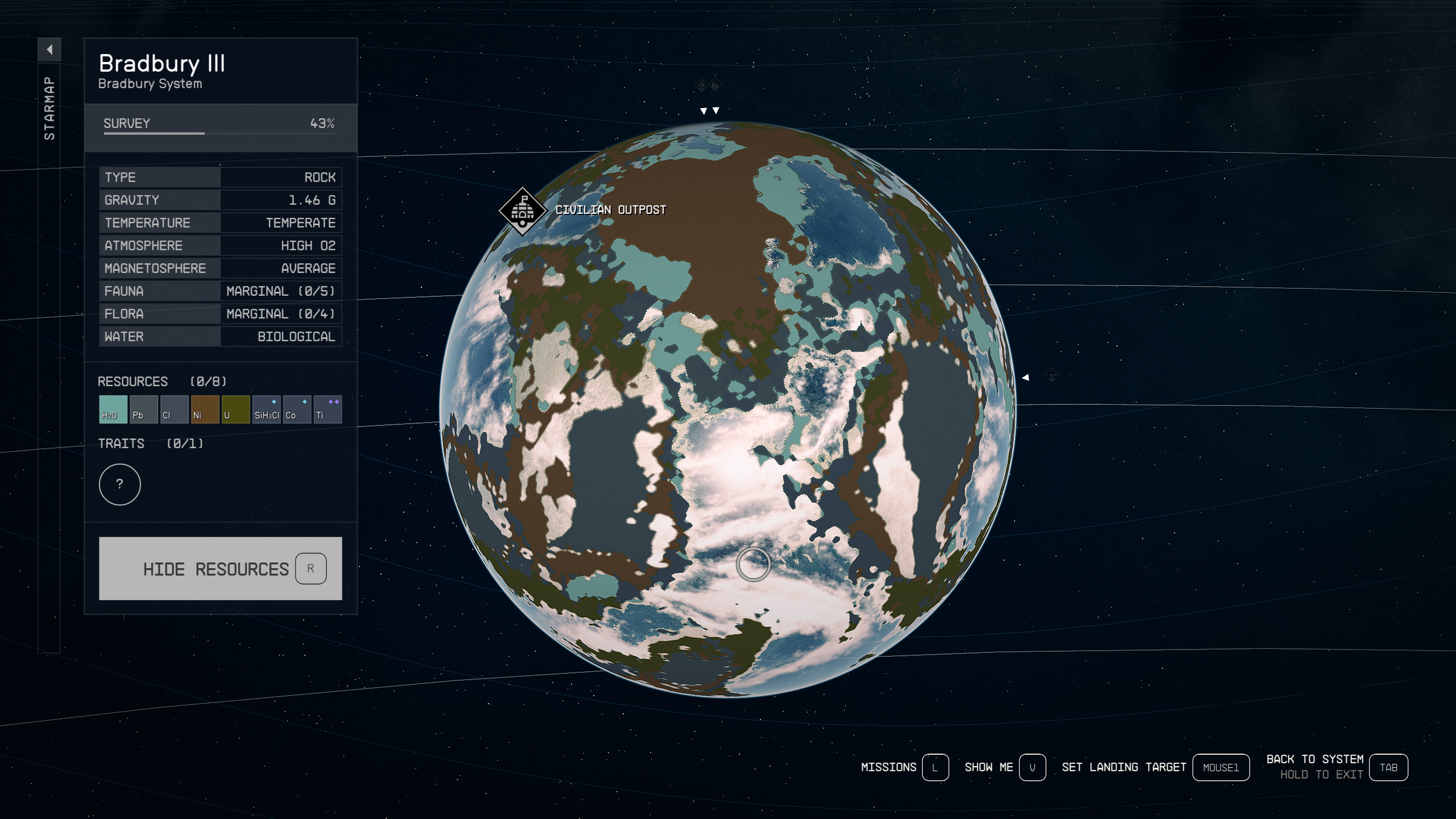

Technically you could fit a whole lot of Skyrims into Starfield's 1,000-world sandbox. It's chock full of desolate moons, tropical planets, pirate bases and futuristic cities. Bethesda loves its massive RPGs, and in Starfield it's made something truly gargantuan. But you'd hardly notice while playing it. Indeed, the scale actually feels considerably smaller than its predecessors. This is not a game for explorers.

Starfield is built for fast travel. You will not be going on some grand space adventure or jetting off to new worlds—you hit a button and end up at your destination. In games as big as this, a fast travel option is a necessity, but unlike previous Bethesda RPGs, it's not optional. It's the only way to get around.

The only time you're really using your ship is during fights, which always take place around planets and moons. If you want to go somewhere else, you target a quest marker or go into the menu, after which your grav drive will be activated and you'll arrive almost immediately.

Space, in Starfield, is merely a container for worlds, and we just have to assume there's absolutely nothing of interest between them.

I get the sense that travel was once going to be a bit more hands-on. Ships have a fuel supply, for instance, which is expended when travelling to new systems. And you can't travel to a system if other systems on that route are unexplored. But since your fuel never actually runs out, fully regenerating after every jump, and it only takes a few seconds to visit an earlier system on the route before jumping to the one you actually want to go to, there are no extra wrinkles here.

This isn't a space sim, so I wasn't expecting my journey across the stars to feel like my bouts of space tourism in Elite Dangerous—but I would be having so much more fun if it did. Elite Dangerous also uses your FTL capabilities to make travelling between systems brisk, but it does so in a way that keeps you in the game, making it feel like you're actually embarking on a real journey rather than simply blinking from A to B. Travelling to distant stars, meanwhile, is an adventure into the unknown where you absolutely need to prepare, lest you find yourself drifting in space without any fuel.

Often, Starfield lets you skip the ship portion entirely, simply jumping from one world directly onto another, leaping all the way across the galaxy in the length of time it takes for the game to finish loading. I hardly feel like I have to move at all, allowing everything I want to just come to me.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I hardly feel like I have to move at all, allowing everything I want to just come to me.

Not only does this make Starfield feel weirdly tiny, it completely unravels one of its central conceits: that space is impossibly huge and incredible and absolutely needs to be explored. The main quest is all about the wonders of space exploration, and even the aesthetic reinforces this, much of it inspired as it is by NASA. But space itself goes largely unexplored, while planetary exploration is a horrendous chore, where the grand scale is merely an illusion.

While you can fast travel between visited locations on Starfield's worlds, you can also trek across them on foot for as long as your patience endures. But even here, you'll never feel like much of an explorer. Between the points of interest—farms, mines, pirate bases, labs—there are just great stretches of nothingness. Maybe some resources for you to mine, or alien critters for you to scan, but they otherwise feel like lifeless husks. I love walking around in Fallout and The Elder Scrolls because I never know when I'm going to encounter an NPC on the road just waiting to send me on another grand quest, or a unique ruin that I'll be exploring for the next hour, solving puzzles and avoiding traps. These kinds of unexpected adventures just don't really exist in Starfield.

Starfield guide: Our hub of advice

Starfield console commands: Every cheat you need

Starfield mods: Space is your sandbox

Starfield traits: The full list, with our top picks

Starfield companions: All your recruitable crew

Starfield romance options: Space dating

The points of interest you'll encounter are just carbon copies of a strangely small number of structures, where everything down to the clutter looks exactly the same. If there are enemies, they'll almost always belong to one of three factions, who look and function so similarly that they might as well all be part of the same club. Like the over-reliance on fast travel, this too contributes to Starfield feeling tiny, because there is so little to differentiate each world from the next one. You'll find the same farms on completely barren moons that you will on lush, verdant worlds. There's nothing compelling me to explore. OK, I might find a legendary weapon, but more often than not I'll just fill my inventory with ammo and resources I can simply find in a shop.

That's really the root of the problem—there's just not much to see in Starfield outside of its busy, quest-filled hubs. Fast travel makes it feel small, but even when you do get to walk around for hours it's rare that you'll find something you haven't seen countless other times. Another dead moon. Another nickel deposit. Another pirate base.

Bethesda argues that Starfield's desolate worlds capture the reality of space. "When the astronauts went to the moon, there was nothing there," Ashley Cheng recently told the NYT. "They certainly weren't bored." It's a pretty weak defence. First of all, Starfield is not a realistic simulation of the cosmos. It's a universe where space cowboys and magical artefacts exist. Bethesda is not beholden to reality, clearly, and the primary purpose of Starfield is entertainment.

Cheng's argument is also undermined by the fact that visiting a planet or moon in Starfield is nothing like being an astronaut setting foot on a previously unexplored celestial body. Astronauts have to contend with so many dangers and surprises that Starfield doesn't even attempt to replicate, all while conducting experiments and research which, again, Starfield fails to offer. Sure, you can scan things and unlock new crafting recipes, but these are perfunctory, repetitious activities absent any unexpected novelties. And every single time I set foot on a new world, I find that someone's already beaten me to it, building factories and mines. I'm not an explorer pushing back the frontier, I'm just some dude using a laser to get more aluminium.

I've really tried to find some joy in visiting new worlds. I've tried to engage with its mechanics and accept Starfield for what it is. I spent four hours surveying a system, planet by planet, moon by moon. It was a big one, and I hated every second of it. Most of the rocks I set foot on were desolate, but when I landed on a jungle moon nothing actually changed. I'd land, exhaustively scan a bunch of stuff until there was nothing new to find, and then fast travel to the next world on the list. Sometimes I'd dip into a point of interest—a cave here, an abandoned factory there—desperate for some surprises. Something I could spin into a compelling anecdote. But nope. With the final world fully surveyed, I was done. Not just with the system, but with the very concept of exploration—at least in Starfield.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.