Procedural quest: Why there are so few police procedurals in gaming

Procedural success stories

In the 1980s, the PC was a platform for RPGs and adventure games. The technology for realistic simulations didn't exist yet, but Police Quest did the best it could with a command line and then Sierra's SCI engine.

"The adventure game genre at the time was very linear," Jim Walls wrote. "Police Quest fit well because police work in itself is linear (you follow the trail of clues and see where they lead). The design of Police Quest was intended to present the player with an array of police activities from the mundane, attending a briefing, to beating back a deadly assault, such as a shootout. I think we did a fairly good job in presenting both ends of the spectrum. Even the mundane briefing was fun because the player could pick up hints, clues and a little humor while being briefed."

Police Quest retrospectives often aren't too kind to the series, criticizing the mundanity of its procedural tasks or that the stories played out in a logical way. But Police Quest was early proof that police procedurals could be playable, and the series was popular enough to see four adventure games before it evolved into the first-person shooter series SWAT.

Few game developers attempted to make procedurals in the 90s, but the PC was a more common platform for simulation-oriented games than the console. FMV games like Spycraft: The Great Game again pushed technology to depict police work (or, in this case, CIA work) as realistically as possible.

As I struggled to find more police procedurals in gaming history, I softened my requirements. There are dozens, hundreds of detective games, often point-and-clicks like David Gilbert's The Shivah , or Westwood's classic Blade Runner , or Gemini Rue . Gilbert cited Discworld Noir as an inspiration. None of those are procedurals, but then I stumbled onto a game that was. It doesn't star a police officer, but it may be the most successful procedural game series ever made.

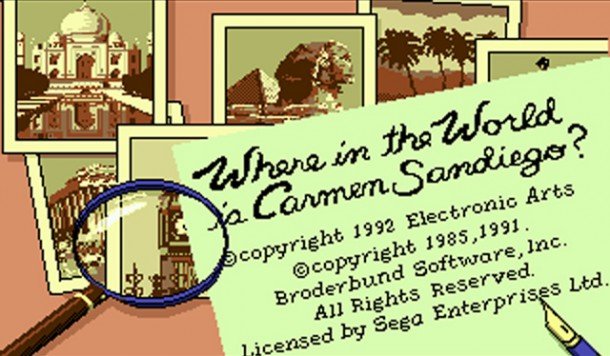

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? is absolutely a procedural game: each case follows the same pattern of heist, investigation, and thief-napping. Carmen Sandiego's crime solving may not be as realistic as Police Quest, but the games use real history, geography, and deduction to solve cases. The underlying system can be gamed, but playing Carmen Sandiego right requires genuine research and learning.

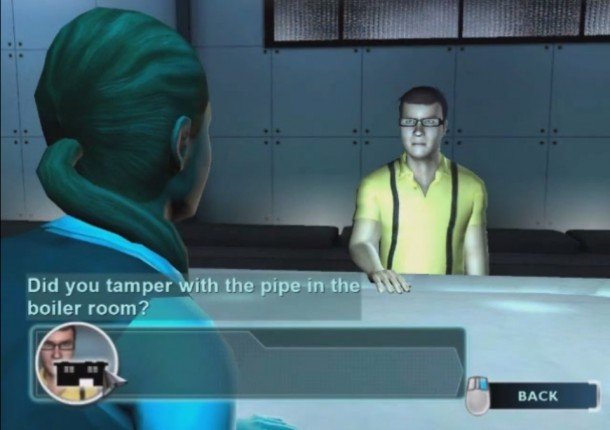

2011's L.A. Noire may be the most high-profile procedural game ever, but it came at a cost—after a five year dev cycle, developer Team Bondi shut down a few months after release. For noir fans, though, the game was a home run. It was a unique police procedural, set in a time period few games have touched, with a lengthy story and amazing attention to detail. It sold more than five million copies in three years—surely that's proof there's an audience for police procedural games.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

So why, in 2014, are there still so few? Indie darling Papers, Please uses a procedural structure to depict the life of an underpaid border agent dictating who immigrates into his country. It's remarkable for how it integrates the mechanics of its gameplay into the theme—shuffling papers and desperately flipping through a rulebook evoke the physical acts, even when done with a mouse pointer. The game also perfectly captures the monotony of performing the same tasks day-to-day. It's affecting, but not fun in the same way procedural TV shows are.

Law & Order and CSI both have licensed games (CSI, in particular, has quite a few), but they're all clearly low budget games aimed at hardcore fans of the shows. They definitely are procedurals—they focus almost completely on the procedure of investigative work, with clues and items to discover and witnesses to interview for various cases. But they don't hold the same appeal as the shows.

If the basic elements are there, why aren't they more popular, when each TV series has lasted for hundreds of episodes? The answer, I think, is that the procedure of police work isn't actually why we watch procedurals at all.

The secret to procedural popularity

Some of the most popular procedurals, like Law & Order and NCIS, barely even attempt realism. Others like Bones and Castle focus more on banter between characters than real crime solving.

Jim Walls has a theory that seeing the process of police work lends a comforting sense of order to the world. "Investigative techniques, such as, forensics, fingerprinting etc. seem to almost guarantee the bad guy gets caught," Walls wrote. "We are inundated on a daily basis with mayhem, chaos and craziness all around the world. It's nice to know there are people working very hard trying to get a handle on it. I believe this is why television procedurals are so popular. They offer a story, a sense of order and closure."

Walt Williams offered another answer: it's the structure of the show, not the content, that always brings us back. "I think the procedural thing, at least in the form of television, has a dual meaning," he said. "[There's] the procedural aspect of: this is the procedure that these people have to go through in order to solve a mystery and convict this person. But also...every time you tune in to watch a show, the show itself is procedural. It's always going to be a stand-alone episode that starts with this and ends with this and goes by the book. Like House, I think, is an example of a procedural, because every episode is ultimately the same thing. So you've got that dual meaning with procedural, which I think makes it a bit trickier to translate over to a video game procedural."

Reliably formulaic plots make procedurals TV's greatest comfort food. We know what to expect. Procedurals rarely challenge us to think too hard, though there are exceptions—The Wire, for example, is beloved for its nuanced writing and acting, not its formula. "The Wire could be considered almost the ultimate procedural, in that it basically takes one case that has a domino effect over five seasons and shows every little intricate aspect of how it spreads out through all the people who touch it, even remotely," Williams said.

If we watch most procedurals for the comforting familiarity, then, how can that essence of the genre translate to games? By Williams' logic, Papers, Please is almost the anti -procedural game. It uses the structure of the procedural to tell a story of grinding monotony, rather than pleasant predictability. For a game to match the popularity of the police or court procedural, it may have to come at things from a different angle.

"We have a different gateway, in games, than other mediums have to bring in new ideas," said Williams. "The Last of Us is basically, at its core, a story of a single father taking care of a teenage girl, and the struggles that coincide. It could be a story that takes place in the real world. They're homeless and [Joel would be] an alcoholic father who can't keep a job and they're going across the country. The exact same story, basically. But it's video games, so we needed zombies. I feel like, with a procedural type of game, you could bring that to the forefront and make that something very popular and desired by gamers, but you couldn't come straight in and make it a straightforward, realistic, cop procedural. You need to come in from that video game angle."

The future for procedural games

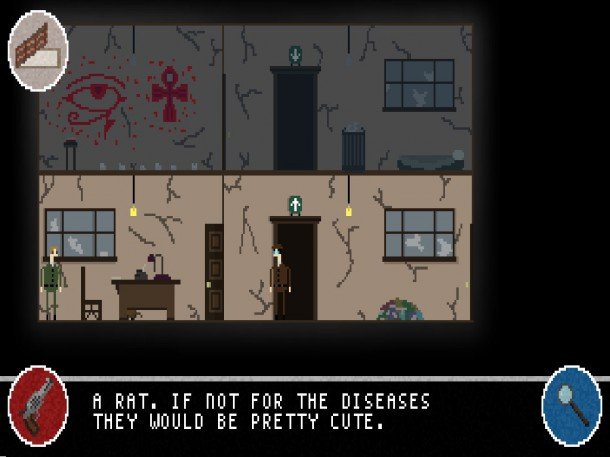

Indie developer Dave Gedarovich has added a third meaning to "procedural" with his crime game Noir Syndrome. It's a noir mystery procedural that's procedurally generated—every case has a randomly selected murderer, randomly generated clues, and NPCs offering hints about the crime. It took him about three months to figure out how to make the investigative aspects of the game fun.

"When I first started making the game, I kept thinking, how can I make this fun?" Gedarovich said. "People wanted more solving a mystery. They didn't come for the action, or walking around collecting food. They wanted to feel smart that they unraveled the mystery and caught the killer. I really had to expand on the notebook, all the clues, I had to make them intertwine and really point toward the killer but not be too obvious so that people still feel good about capturing them."

Gedarovich sees procedural generation as a potential solution to the challenge of making repetitive police practices fun. Episodic delivery is another format that seems perfect for procedural gaming.

"When I play some episodic games I think about how powerful the format can be, how you get attached to these characters over a long period of time," said David Gilbert. "[Walking Dead] would not be nearly as effective if it was played all in one sitting. But because it's released monthly, these characters sit in your head for a little bit of time, and it's like reconnecting with them each episode."

Williams agreed, but pointed out that a procedural wouldn't necessarily work within the same kind of episodic setup as The Walking Dead.

"I think the season pass model kind of kills it, to be honest. When you buy a season pass, you're expecting some kind of arc. If, instead of putting out a season pass, you were just like, this is the game that we're going to be doing, and we're going to put out an episode every couple months as we finish them, and we'll keep putting it out as long as you guys keep enjoying it and wanting to buy it. You could work in bigger story structure stuff that connected each episode. The season pass, I feel like, instantly gives the consumer a mindset of, I'm buying a big connected experience, versus the episodic procedural-type format."

From a business perspective, of course, game developers would rather get the money up front to fund development, hence the season pass model. Gilbert also said that the gaming audience just doesn't have faith yet in episodic delivery—from developers other than Telltale, that is. Both he and Williams see that as an enticing future for story-driven games.

Jim Walls, who is still working on the design for Police Quest revival Precinct, sees another, perhaps simpler future for a police procedural.

"My take on game design has not changed over the course of my career," Walls wrote. "I still want to make the most realistic police game possible. Having said that, I do believe today's technology is becoming more and more in line with the way I have always wanted to design a police game...technologies of interface design are forever evolving. That's why we are excited about new tech like Oculus Rift, which puts the player into a more physical space of the experience. Virtual reality would be the ultimate step forward for the police procedural."

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).