I bought a $600 graphics card to play Quake 2 with ray tracing

Somehow a game from 1997 convinced me it was time to upgrade.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

I bought an RTX 3070 in December, but it wasn't to play Cyberpunk 2077 with everything on ultra. It was to play Quake 2, a shooter made back in 1997. When Nvidia first released its new 30-series graphics cards last fall, I convinced myself I didn't need one. My trusty GTX 1080 was still working just fine, and buying a new card right now is truly a nightmare, with stock selling out in seconds at stores like Best Buy and Newegg. Who needs the stress?

Then I played Quake. I beat Quake. I loved Quake, even 25 years later. And I thought, man, Quake 2 with ray tracing, which Nvidia released in partnership with Bethesda back in 2019, sure does look pretty cool. I want to play that.

Was it $600 cool? My head said no, but my heart said yes, and after two weeks of constantly checking stock alerts, I managed to snag a Gigabyte RTX 3070 Vision on Newegg. It came with a power supply I didn't want (Newegg knows it has PC gamers over a barrel, so it's selling the GPUs in combos with PSUs and RAM). But a few days and $744.56 dollars later, I could play the hottest PC game of 1997 with fancy new lighting.

And it was worth it.

I mean, maybe playing Quake 2 with RTX on wasn't worth $744.56 by itself. I wouldn't recommend anyone spend that much money to play exactly one videogame. But Quake 2 RTX made me realize that this is exactly what I want out of ray tracing.

In modern cutting-edge games like Control or Cyberpunk 2077, ray tracing is like the shiny cherry on top of a realism sundae. The lighting and reflections may look amazing, but everything else is already so detailed it's hard for them to really stand out. Quake 2 RTX's simple geometry and textures put all the focus on the lighting, and in doing so completely transform the game.

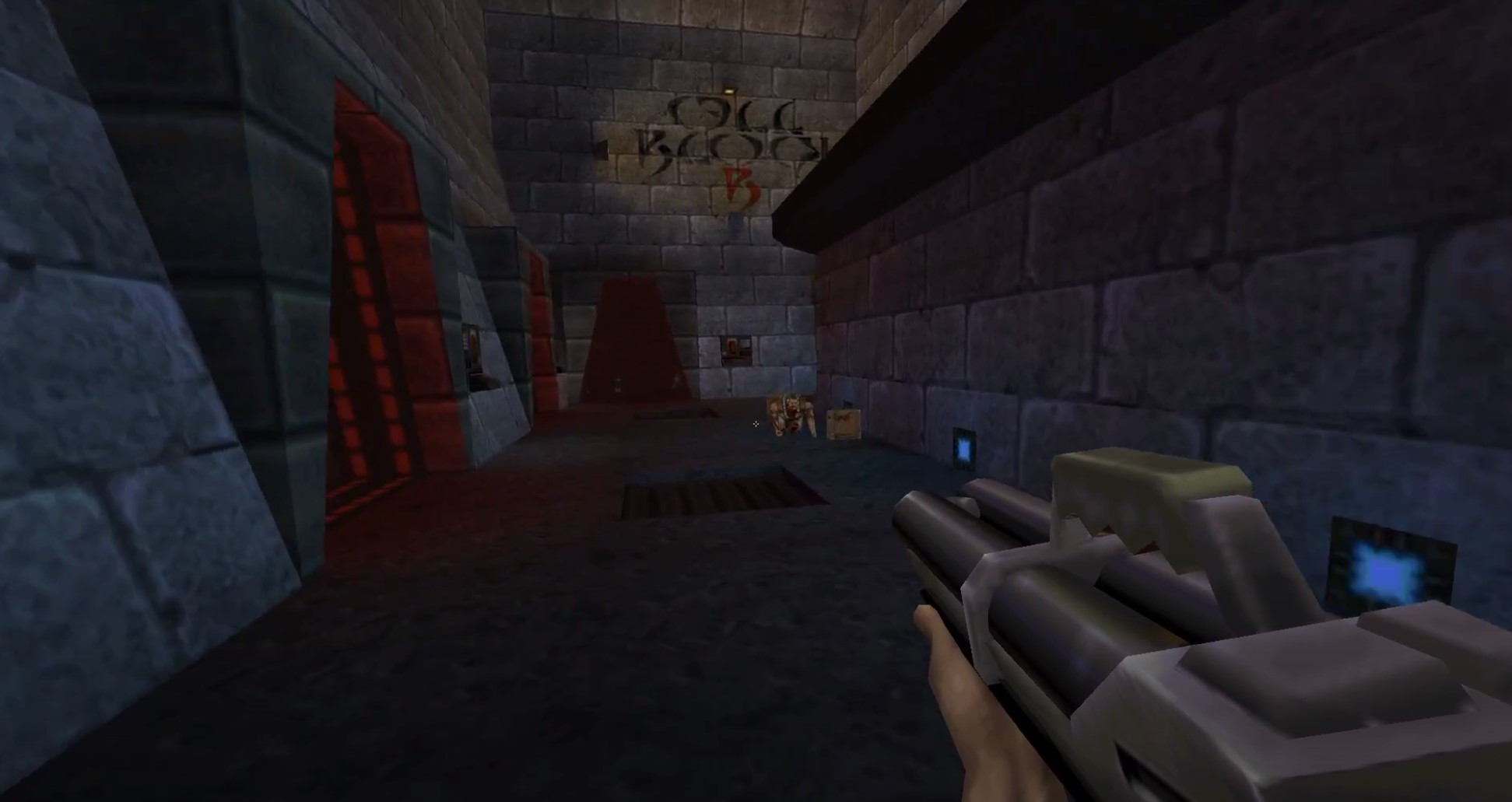

Quake 2's color palette is dominated by browns and grays, with the occasional exciting bit of glowing red lava. There are wall sconces and bits of colored lighting here and there, but they never stand out, or cast a glow throughout the room they're in. It was still amazing tech for 1997, of course. PC Gamer called it "the most sensational and subtle shooter ever" in a 1998 list of the 50 best games of all time, where it took third place.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"Subtle" for the time was probably referencing the fact that some enemies will double over in pain when you shoot them, which in 1998 passed for realism but in 2021 is a little comical when it happens every single time. And it gets in the way of the satisfying flow from one headshot to the next. If there's one thing id Software games absolutely never needed, it's subtly.

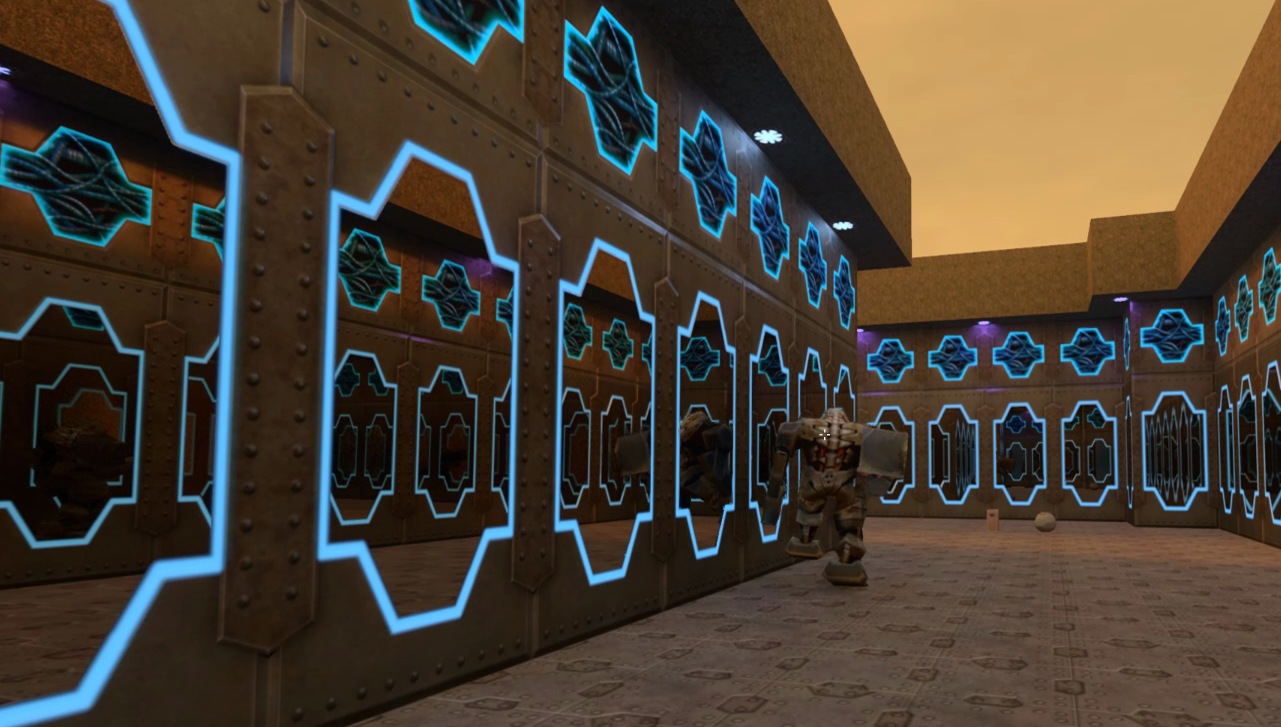

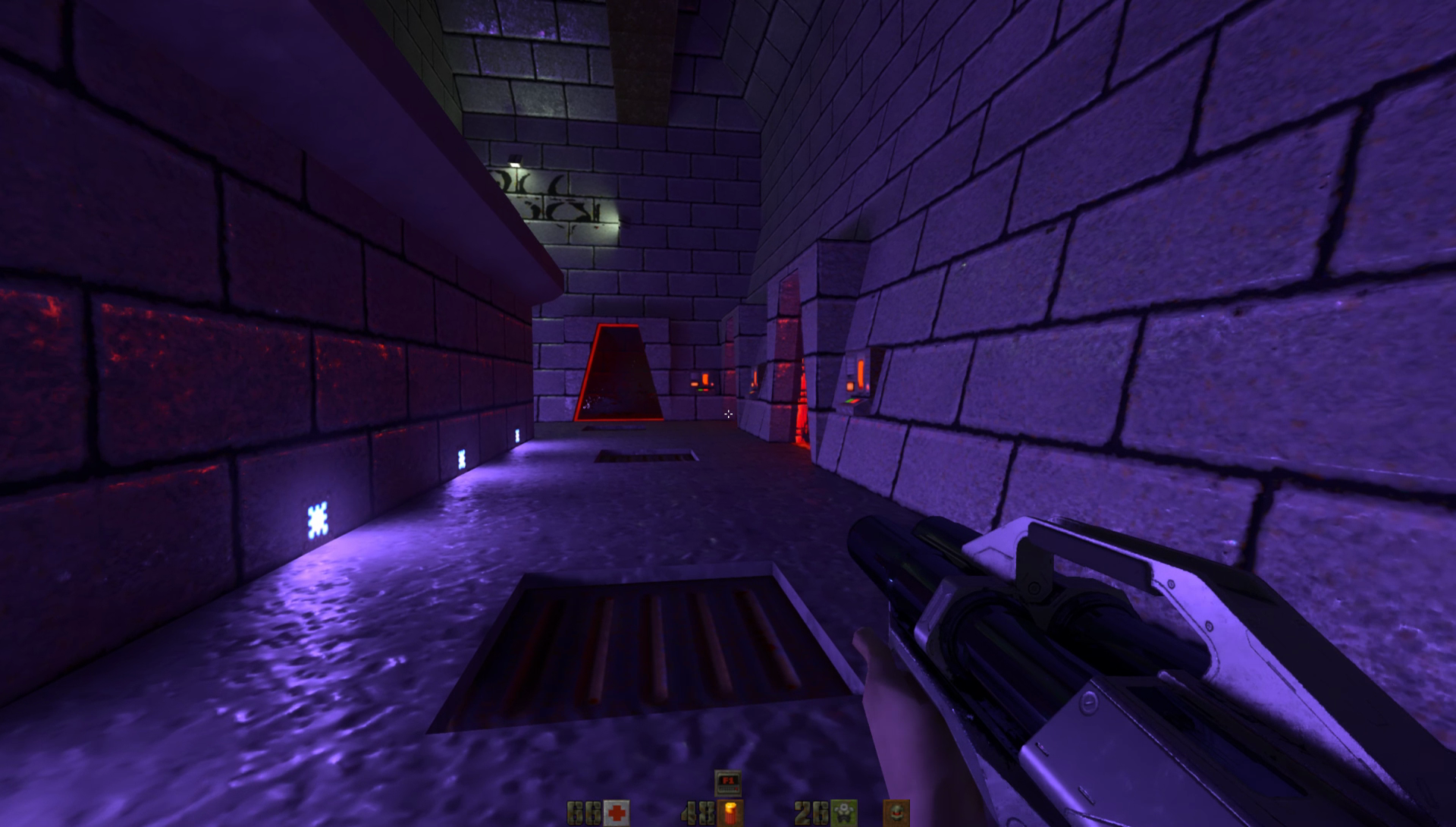

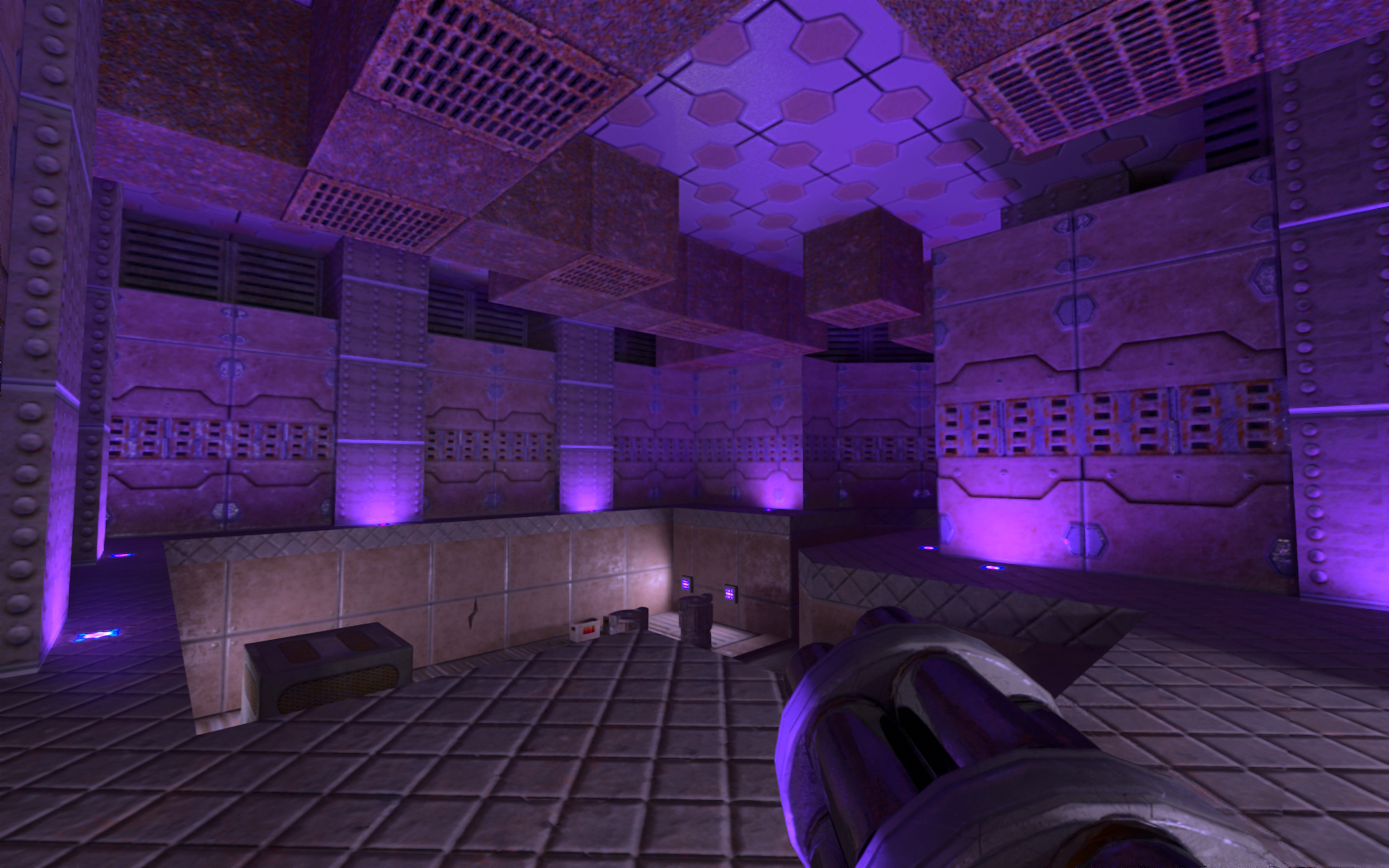

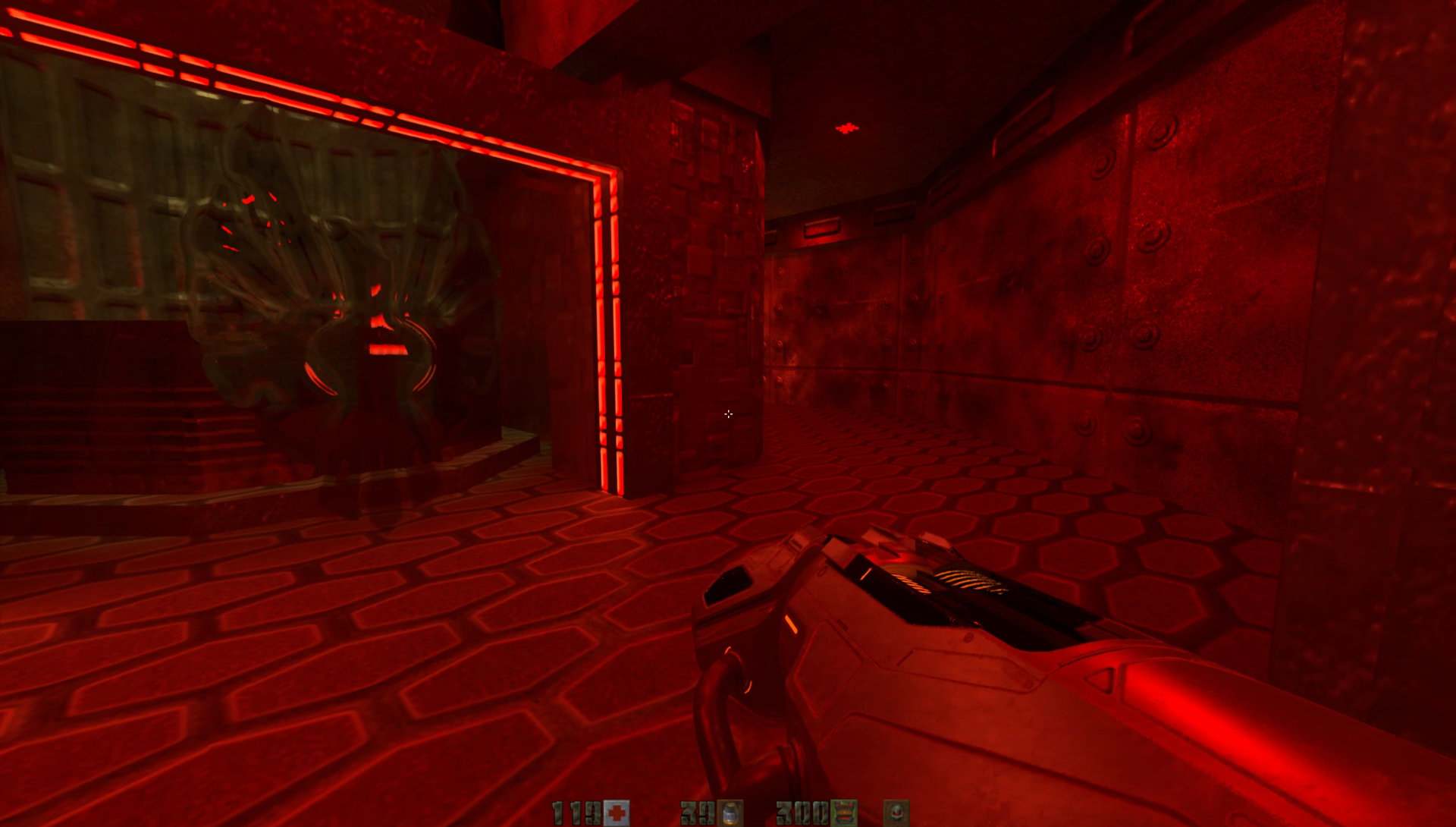

And Quake 2 RTX is not subtle. It wields ray traced lighting like an artist who's just been miraculously cured of color blindness, drenching one corridor in purple, another in sickly green. Just look at this difference between a couple rooms:

If this were the only version of Quake 2 readily available, I might look at it in the same way as the Star Wars Special Edition—shamelessly overwriting history with a wildly different aesthetic sensibility. But Quake 2 RTX does not erase or replace the original game—id made the engine open source in 2001, and you even need to own the original to play RTX, so all those browns and grays will be preserved forever.

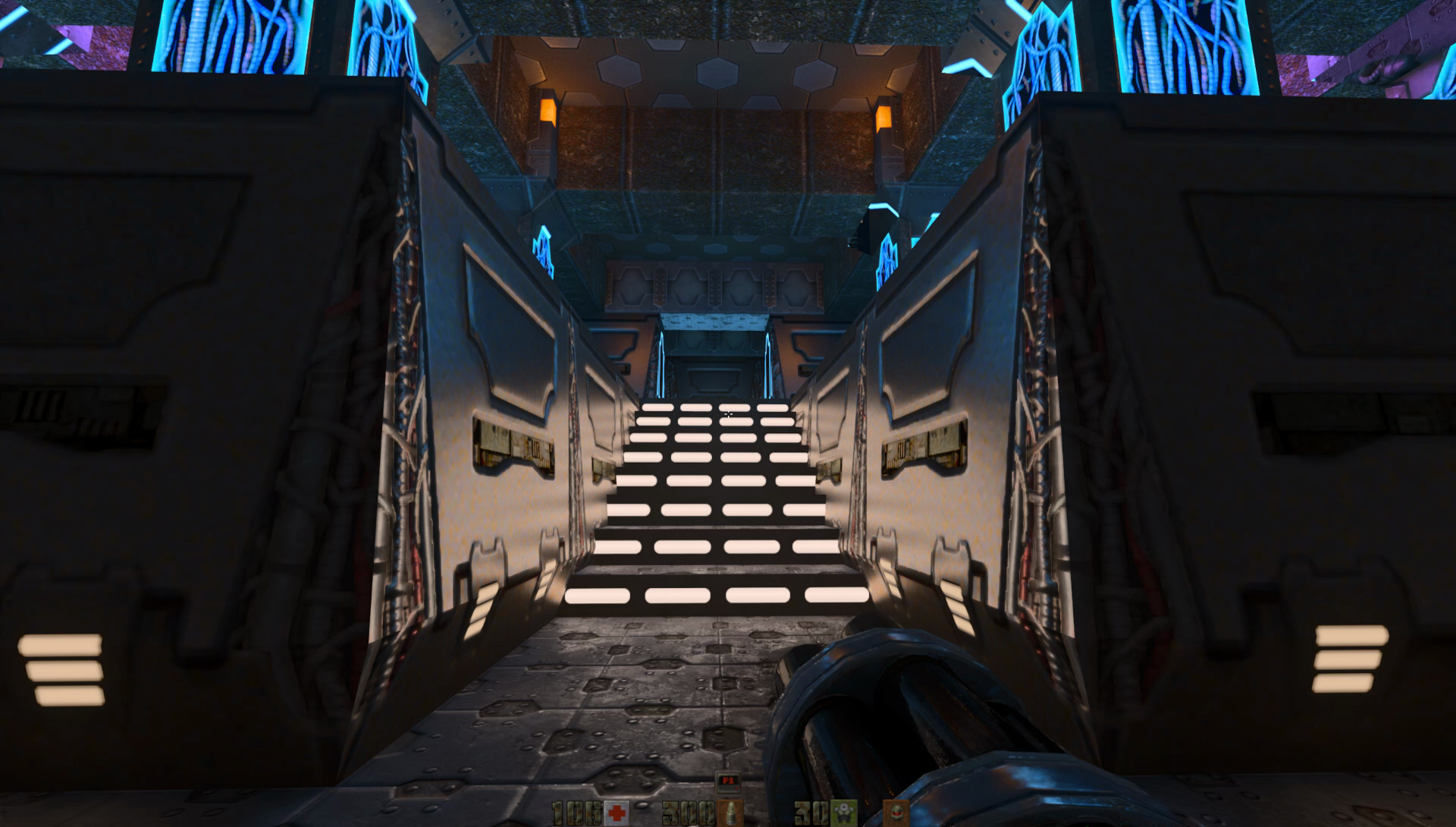

The deeper I played into Quake 2 RTX, the more significant the ray tracing felt to me. At first, it's easy to go: Ooh, look at those water reflections!

Or to be distracted mid-firefight by how the blue spiral of a railgun and the BFG's blob light up the room as they zip across the screen:

But after a few hours, it started to seep in that this stuff wasn't just eye candy. For example, Nvidia added a flare gun into the game to make it easier to see in the dark—a vital tool in Quake 2 RTX, because the dark is now really dark. Where there isn't an in-world light source, you have to supply your own. This changes what it's like to explore the nooks and crannies of the Strogg base, giving it a bit more of the horror vibe id would later go for in Doom 3.

Playing Quake 2 RTX absolutely gives Quake 2 a different feel, but I think it uses the technology in ways id's developers would've tried themselves if they could have back in 1997. The colorful lighting isn't just for show—it quickly became the way I navigated the corridors of the Strogg base, remembering I needed to pass through a striking red room to get back to a previously locked door. Unlike Quake 1's standalone levels, Quake 2 uses a hub design, where you're frequently backtracking through previous areas after completing a secondary objective. I got lost in the hallways more than once, and would've spent way more time wandering in vain without the lights to guide me.

Ray tracing helps iron out some of Quake 2's more tedious moments and just generally make its spaces more interesting to explore. When Nvidia's designers really went over-the-top with colored lighting, I realized they had changed the kind of sci-fi Quake 2 evokes. The original game was James Cameron's Aliens, rendered in the finest detail that 12 megabytes of video memory could produce. But Quake 2 RTX's aesthetic, in its most dramatically lit corners, is pure Star Trek: The Original Series.

Visions of the future in the 1960s tended towards bright, bold colors, and Star Trek didn't have CG to create detailed imaginary backdrops. On the Enterprise especially, the lighting does so much of the work in setting the tone on the ship. It's exciting! Compared to the more peaceful, businesslike flat lighting of Star Trek: The Next Generation, The Original Series' shadows and gel filters ooze excitement and danger.

Compared to what games look like today, Quake 2's rudimentary level geometry feels like the game equivalent of those simplistic 1960s sets. In both cases, the lighting gets to be the dominant visual effect.

This approach is what really convinced me that ray tracing is cool technology for games. I still don't particularly care about it for brand new games—I'm far more interested in how powerful a design tool lighting can now be for old ones. Or, maybe more realistically, for games like Dusk and Amid Evil, which aim to recreate the early 3D aesthetic. I want to see more modern retro games embrace ray tracing as a way to put a new spin on old styles, in the same way that Guilty Gear Xrd used cel-shaded 3D to emulate 2D sprites.

Do it for me, game developers—otherwise, what else am I going to play on this $600 graphics card?

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).