Nearly 25 years on, you should still play Quake

The blueprint for 3D shooters still has a thing or two to teach today.

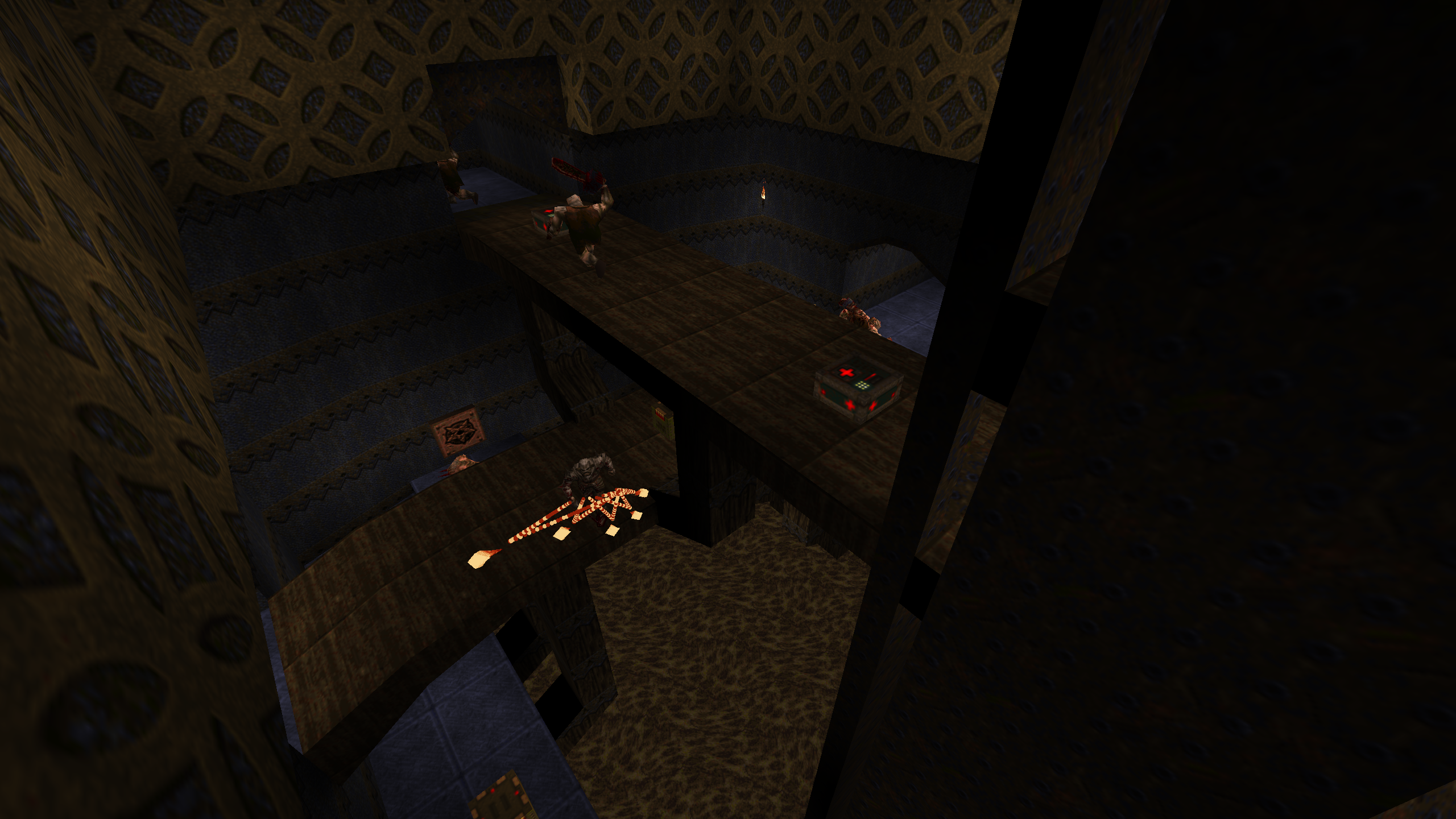

A wizard lives here, supposedly. Either he's out to lunch, or someone at id Software in 1996 came up with the name for Quake E2M5, "The Wizard's Manse," and decided it was too cool—sorry, too metal—to change, even when the wizard himself never makes an appearance. Forgivable, considering it's one of the most tightly crafted levels in a game full of them.

Another Quake lesson: a small level is almost always more impressive than a big one.

I've been on a classic FPS tear recently, playing a mix of old-old and designed-to-feel-old shooters like Amid Evil, Dusk, Duke Nukem 3D, and Quake. With so many games today designed to keep you playing for a hundred hours, it's refreshing to pick up a shooter that lets you ice skate uphill at Olympic speeds and tear through a dozen levels in an hour or two. But with Quake, it wasn't really the speed that pulled me in. Even closing in on 25 years old, Quake still surprisingly feels like a game with plenty of wisdom (though again, no wizards) to offer.

It's simple wisdom, really, but few shooters have outdone id's level design even with two decades to study them. Here's a basic lesson Quake imparts in The Wizard's Manse: Climbing up a staircase and realizing that you're now standing on a platform above the room you fought through a few minutes ago is more empowering than any shotgun.

It's a perfect videogame moment, closing the loop on the thought "How do I get up there?" with the sudden satisfaction of doing it without even realizing.

Another Quake lesson, which goes hand-in-hand with that one: a small level is almost always more impressive than a big one. The Wizard's Manse is about a dozen levels into Quake's campaign, and was the first one to really make my lizard brain stop and pay close attention. John Romero once tweeted it's his favorite level in the game, and I can see why: E2M5 channels id's excitement with three dimensions into an intricate construction of crisscrossing walkways, looping back over itself twice before you reach the end.

It's so easy to chew through these old shooters without really stopping to look around. And in Quake, there's usually not a whole lot to look around at. A few levels borrow Doom's sci-fi aesthetic, but each episode invariably descends into a vaguely Lovecraftian castle or dungeon. Quake's defining characteristic is the color brown. Even the water is muddy.

Doom is remembered for its amazing maze-like levels, while Quake's campaign is mostly remembered for what it wasn't: the more RPG-esque fantasy adventure John Romero wanted to make, which wouldn't have been a shooter at all. You'd have ended up some guy named Quake carrying around a giant hammer. It ended up a shooter, of course, an awful lot like Doom but in full 3D. But when Quake tries to show how big of a deal those state-of-the-art polygons were, it really shines.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The Wizard's Manse starts with one of Quake's most underused gimmicks: Enemies fighting each other. I walk out onto a long bridge, then immediately retreat back to the cave I started in. I get lucky: an ogre and two Death Knights follow, and a poorly aimed fireball blast into the ogre's back makes him take a chainsaw to the Death Knight instead of me. The bridge and a couple grenade-throwing ogres outside are the manse's lookout tower, and a warm-up for a level that's going to constantly ask to watch out above.

The manse's main room—I guess crisscrossing walkways over a pool of brown water once passed muster as a foyer?—forces me to skirt the left side of the room until I find a button that raises the right side's walkway. When I leap (okay, fall) into the water to avoid a grenade, I'm rewarded with a few goodies that recover the ammo and health I just lost. It's a quick swim to get back, and also includes a great bit of foreshadowing: a barred-off underwater passageway that I immediately want to find my way into.

One flight of stairs later and I'm under another set of walkways and above another pit of water, but jumping in this time yields something even better: a passageway that leads to a quad damage powerup and a way up, level with the assholes who were just raining grenades down on my head. The powered-up super shotgun turns them into chunks.

The next room is simple, yet one of the most memorable in all of Quake: a series of narrow platforms over an acid pit. They pop out of the wall with a thunk when I get close, forming stairs for me to hop up. Finally I'm on the top floor, looking down two levels and wondering if the wizard appreciates this view.

The graphics in the Wizard's Manse are indistinguishable from the rest of Quake, but those little mechanical steps give it character. They make me think about how the wizard gets around his house, and the satisfaction he probably took in building this whole place.

He had a small plot of land, so he had to be creative. It's basically just four rooms—10 minutes of winding and climbing would take about 10 seconds laid flat. Usually vertical videogame levels guarantee a groan, at some point, when you fall off the top story and have to walk your way all the way back. But Quake's levels are so dense, that's never a problem. There's always a sneaky elevator or alcove that gets you back to where you were in seconds.

Finally, at the end of the level, The Wizard's Manse drops one more Quake lesson: in a game all about empowerment, having your power stripped away is more impressive than any new gun.

A glowing button entices me into a cage, which lowers me underwater and into the shaft I saw earlier (aha!), and then slowly carries me down a long passageway. I begin to drown, watching my HP tick away with each choking gasp. It lasts just long enough for me to worry that I've screwed up, and then the cage crests the surface and I can breathe again. Just the kind of contraption a wizard would build to entertain himself and freak out the in-laws. Without a line of dialogue, The Wizard's Manse still manages to tell some little stories.

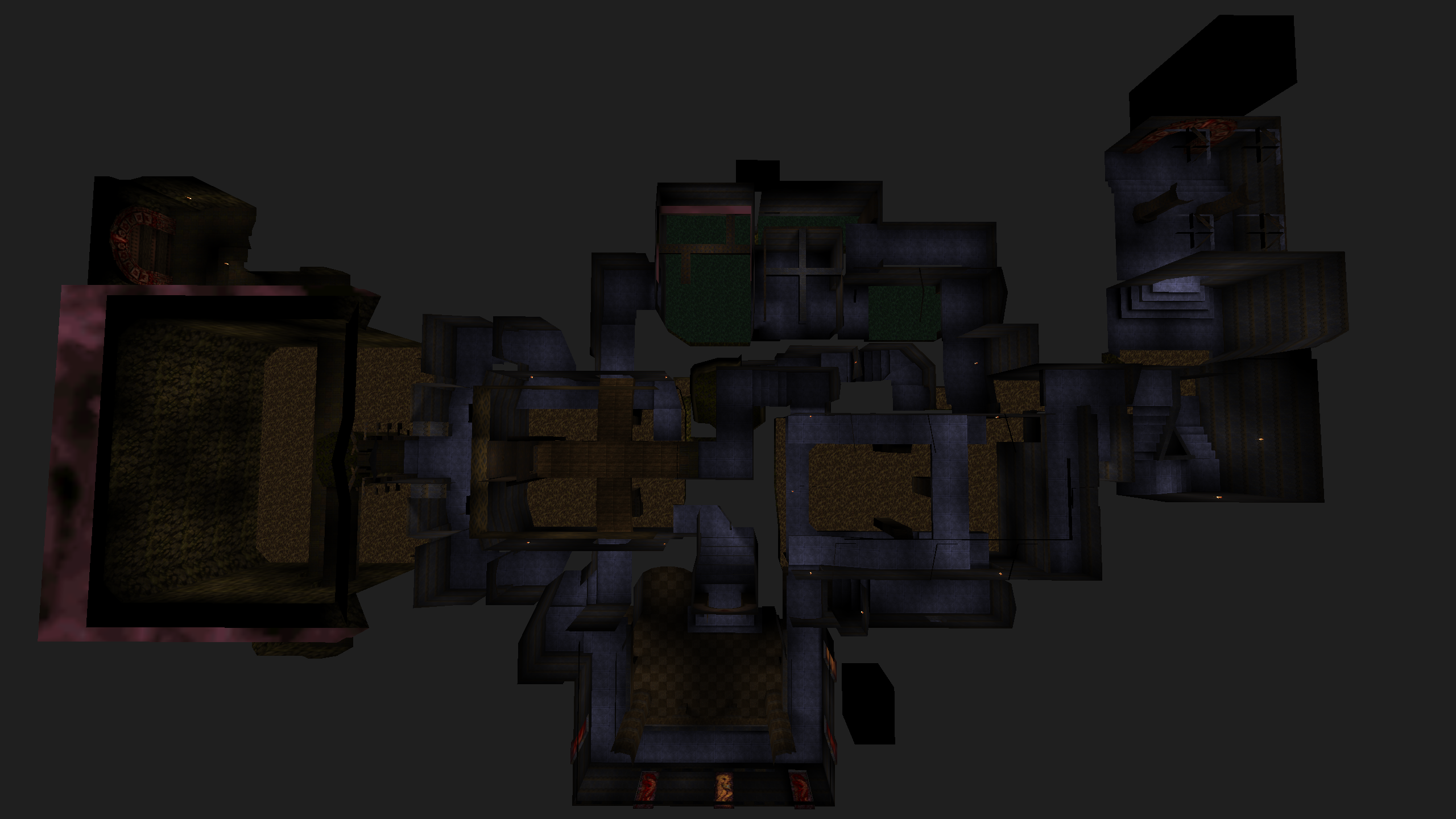

The Wizard's Manse isn't a flashy level, but it sets up some of Quake's best ideas to come. The next level, The Dismal Oubliette, closes out episode two with a great centerpiece, an L-shaped bridge that eventually rotates as you progress and find buttons that activate it. At the start, it taunts you with paths you can't take, one holding a tantalizing 150 point yellow armor. But there's also armor in the very first room you start in, which means that yellow armor is actually a premonition: You're gonna need that later.

The Dismal Oubliette has just as much fun with medieval contraptions as The Wizard's Manse. Its first room off the center bridge makes you press a switch to raise a set of stairs out of a pool, and another switch seems like it'll probably rotate that bridge you just left. But no, it actually opens a secret door, the kind you usually have to discover with a shotgun blast to a suspicious wall.

Behind this lies a whole new area with an intimidating tower (and moat!) in front of you, guarded by a lightning-throwing Shambler. In hindsight, hiding all this behind a secret door makes a lot of sense if you know what oubliette means. The tower ends with a satisfying loop back to the far side of the moat you had to cross to reach it, and the second area that spokes off the center bridge also sends you up to two enemy-packed floors on an elevator before returning to the ground floor to claim your prize, the final bridge button.

This style of design still exists in games today, but most big-budget shooters are about crossing a larger map and surviving setpieces along the way. Nothing wrong with that, but it doesn't trigger the almost Pavlovian reaction my brain has to closing a loop in a classic shooter, where every accomplishment ends in the revelation that all this time, I was actually just feet away from where I started.

It's like a slight-of-hand card trick: Even when I know it's coming, it's still a tiny thrill.

Quake doesn't pull out that trick in every level, but when it does it does it well. It doesn't look so hot these days, and the fantasy setting is about as deep as a kid putting on his robe and wizard hat to cosplay. Play a few levels, though, and you'll understand why throwback shooters like Dusk skipped 20 years of progress to go back to Quake's school of level design. It's still a riveting textbook. Just, you know, with guns.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).