Battlefield had a messy predecessor, Codename Eagle, that predates even DICE’s involvement in the series

The millennium-era reviews make for funny and illuminating reading.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Weird Weekend is our regular Saturday column where we celebrate PC gaming oddities: peculiar games, strange bits of trivia, forgotten history. Pop back every weekend to find out what Jeremy, Josh and Rick have become obsessed with this time, whether it's the canon height of Thief's Garrett or that time someone in the Vatican pirated Football Manager.

Check the credits for Battlefield 6 and you'll find a laundry list of long-suffering studios.

Criterion, which used to be a household name in the British racing genre before its inexplicable relegation to support studio status. Motive, which was merged with BioWare Montreal after the disastrous Mass Effect Andromeda—a cultural clash that, according to Bloomberg, ultimately led to the cancellation of an original series after six years of development. And Ridgeline Games, an outfit set up by Halo's Marcus Lehto with a mandate to get Battlefield's singleplayer into shape, yet closed down before it could do so. As evidenced by the state of this year's campaign.

Then there's Ripple Effect—the artist formerly known as DICE LA, and before that Danger Close, aka EA Los Angeles, which once upon a time was called DreamWorks Interactive. The latter was responsible for the invention of Medal of Honor, but hey—why keep track of the studio that birthed the military FPS? Why not bury its legacy beneath a succession of aliases?

EA now groups these teams under the moniker Battlefield Studios. That's 'BF Studios' for short, or for long, 'every studio we haven't quite managed to kill via corporate clumsiness, plus one we actually did'.

But there's always DICE. A name to cling to, that doesn't change or disappear. For as long as there's been Battlefield, DICE has been making it. Right? Well, not exactly. Turns out the origin story of the PC's crumbliest shooter is a tad stranger than that.

Back in the '90s, DICE made rally and stock car racers. It coded games with titles like Pinball Dreams, Pinball Fantasies and, why not, Pinball Illusions. Then, in 2000, it acquired a developer called Refraction Games. (That's where it picked up Patrick Söderlund—who eventually parlayed his position at DICE into a high-powered role at the peak of EA's executive mountain, then set up the studio behind Arc Raiders and The Finals.)

Into the bargain, millennium-era DICE also picked up an in-development FPS named Battlefield 1942. Yep, the first-ever game in the series was inherited. You may already know that the engine that preceded Frostbite, which powered Battlefield until the making of Bad Company, was called Refractor. Now you know why.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Battlefield 1942 was a huge success, establishing the bombastic multi-vehicular paradigm that the series has stuck to ever since, as well as that earworm theme tune. Its release made DICE famous, and laid the runway for Battlefield 6 to become 2025's biggest shooter. But it wasn't Refraction's first attempt.

No: part of the reason 1942 turned out so well is that its developers had a trial run. The year before the acquisition, Refraction put out a messy FPS dubbed Codename Eagle—considered by those who remember it to be Battlefield's spiritual starting point.

Where better to go for a rundown of Codename Eagle's strengths and weaknesses than the review from PC Gamer US—published in the same month the bridge from The Bridge officially opened for traffic? An important time for both the future of the Scandi FPS and for Scandi noir.

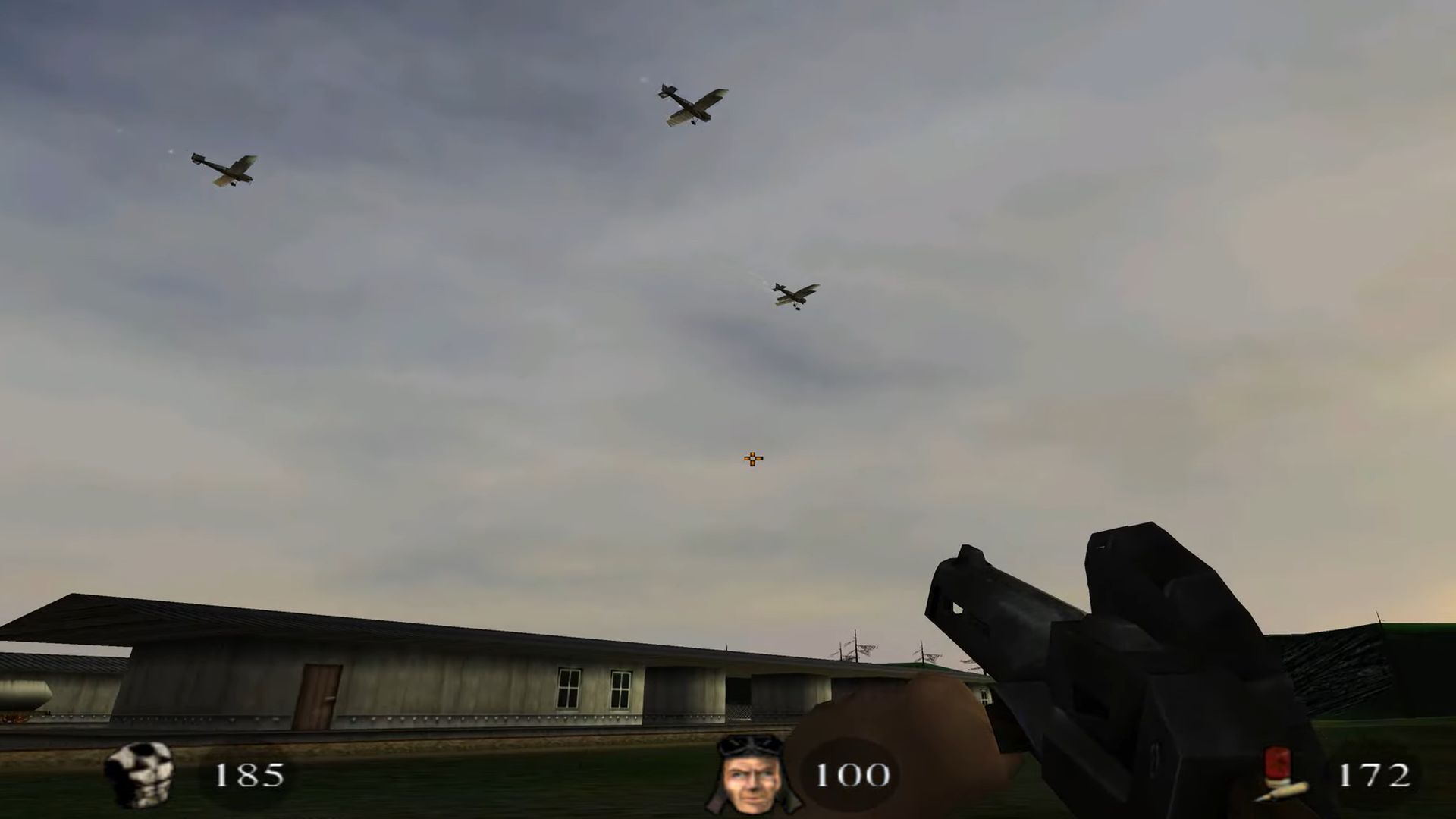

"The addition of vehicle play adds something to what would otherwise be a poor FPS, once you master the controls," writes our reviewer, Don St. John. "That's not easy—getting a handle on the trucks and boats is no simple matter, and flying the biplane is downright difficult (ridiculously so without a joystick)."

Plus ca change, Mr St. John. Every time a rookie pilot sends my engineer plunging into one of New Sobek City's construction sites, I imagine their flustered excuses to go something like Don's: "Even a tap on the controls sends your plane careening around, and maintaining altitude is quite tough to accomplish." Give it 100 hours and you'll be the bane of every pedestrian on the map, I reckon.

St. John also dinged Refraction's FPS for its blocky graphics, and the fact that you needed to download a patch to access more than four multiplayer maps—no small deal on pre-broadband internet. "But it does have its fans," he acknowledged. "And offers a different twist on the genre."

Sure enough, a few other critics from the time told breathless anecdotes of desperate dashes to anti-aircraft guns to deal with divebombing opponents, and recognised a kernel of something genuinely innovative—the same nascent magic that DICE presumably saw when it pulled out its checkbook to buy Refraction.

Still: it's reassuring to any of us who've failed to predict a smash hit that Erik Wolpaw, a future writer on Portal, Left 4 Dead and Psychonauts, dismissed Codename Eagle as "enthusiastically mediocre".

"In a bold display of marketing chicanery, the version of Gamespy packaged with the game doesn't actually support Codename Eagle," he observed dryly in his Gamespot review. "And in fact, you need to pay extra for a registered copy of Gamespy to locate any Codename Eagle servers."

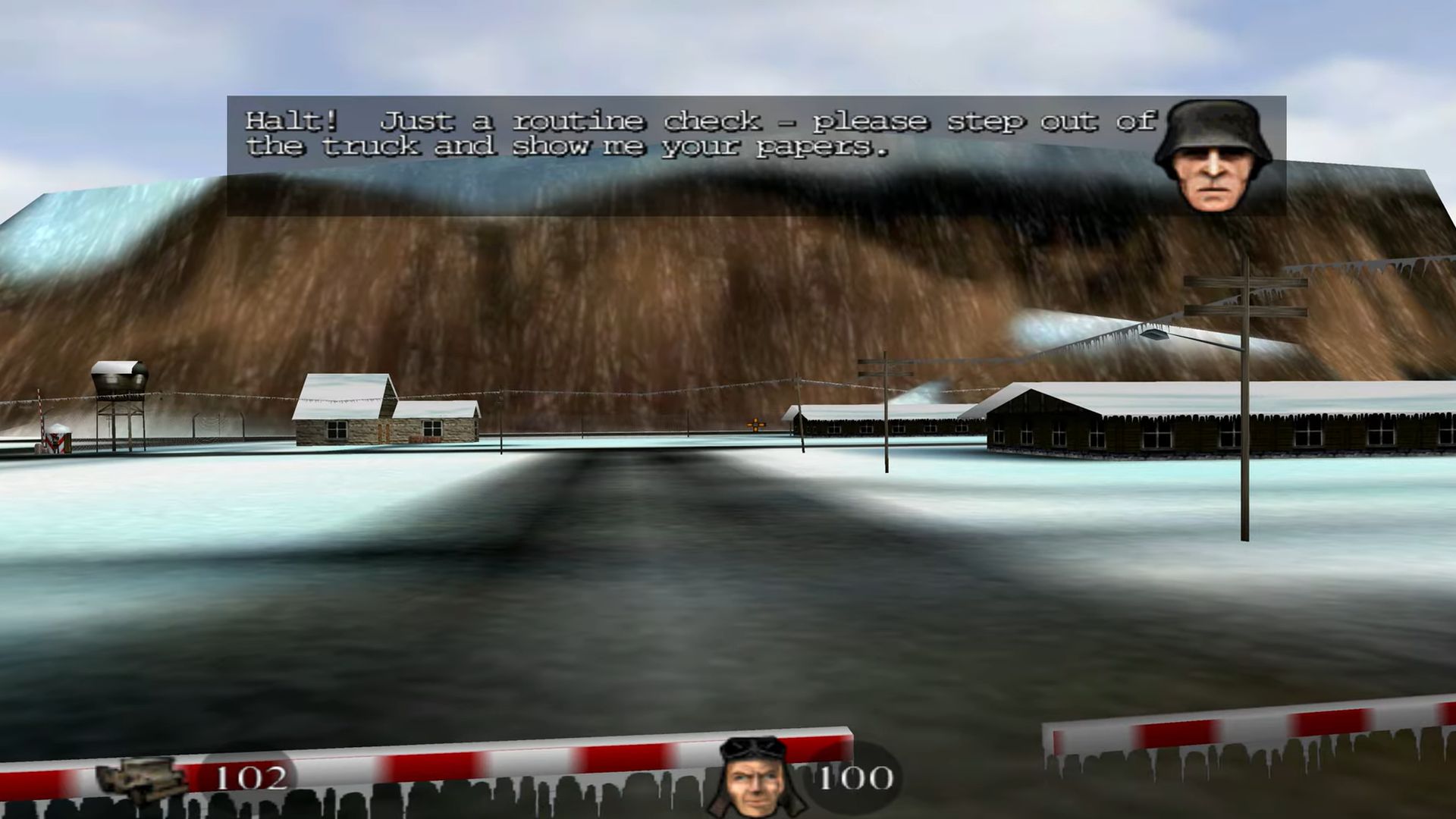

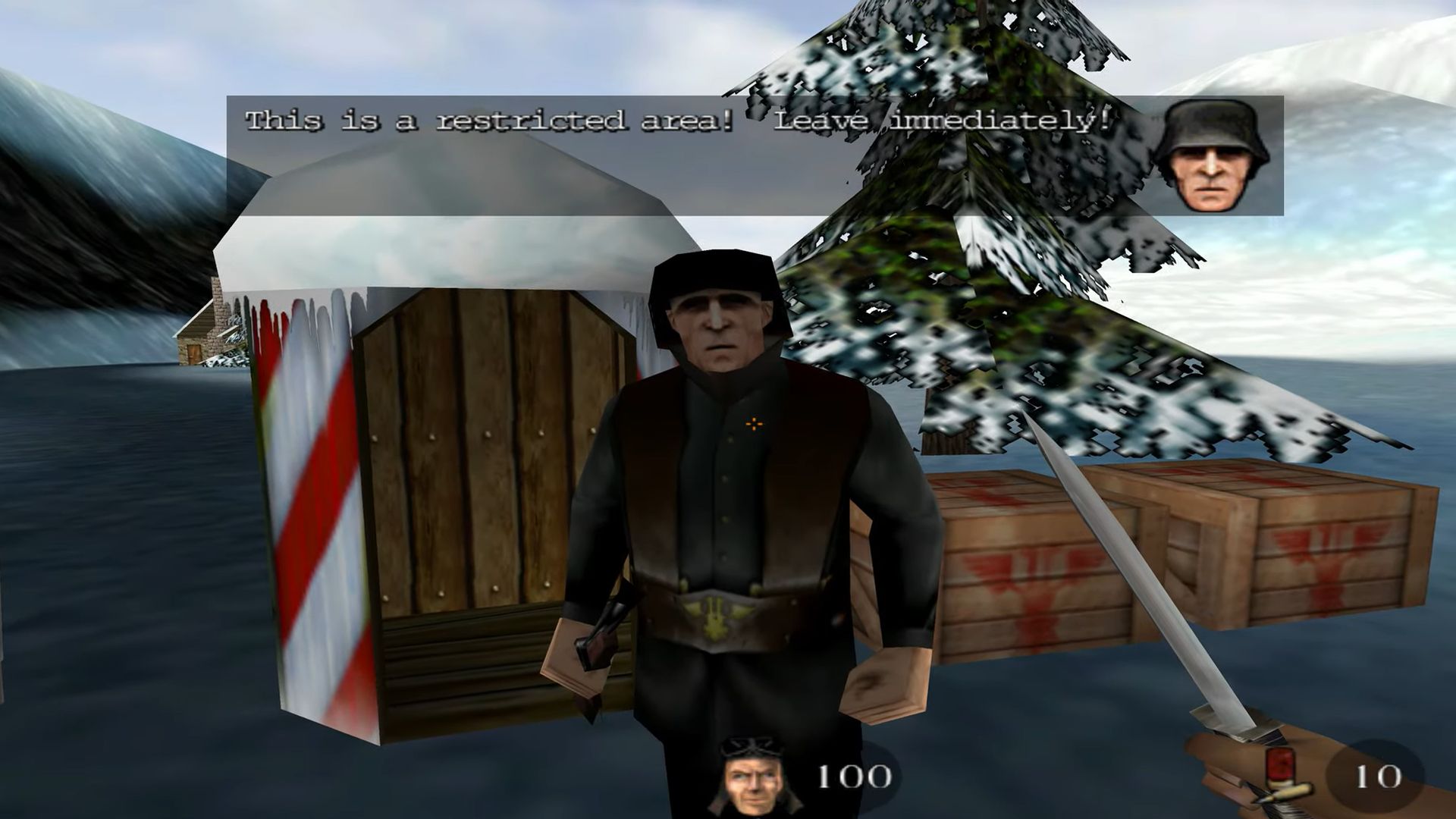

It's clear in retrospect that many missed the potential of Codename Eagle because they weren't looking squarely at its multiplayer, but rather were distracted by its solo campaign—set in an alternate history where the Russian Empire dodges the Bolshevik revolution.

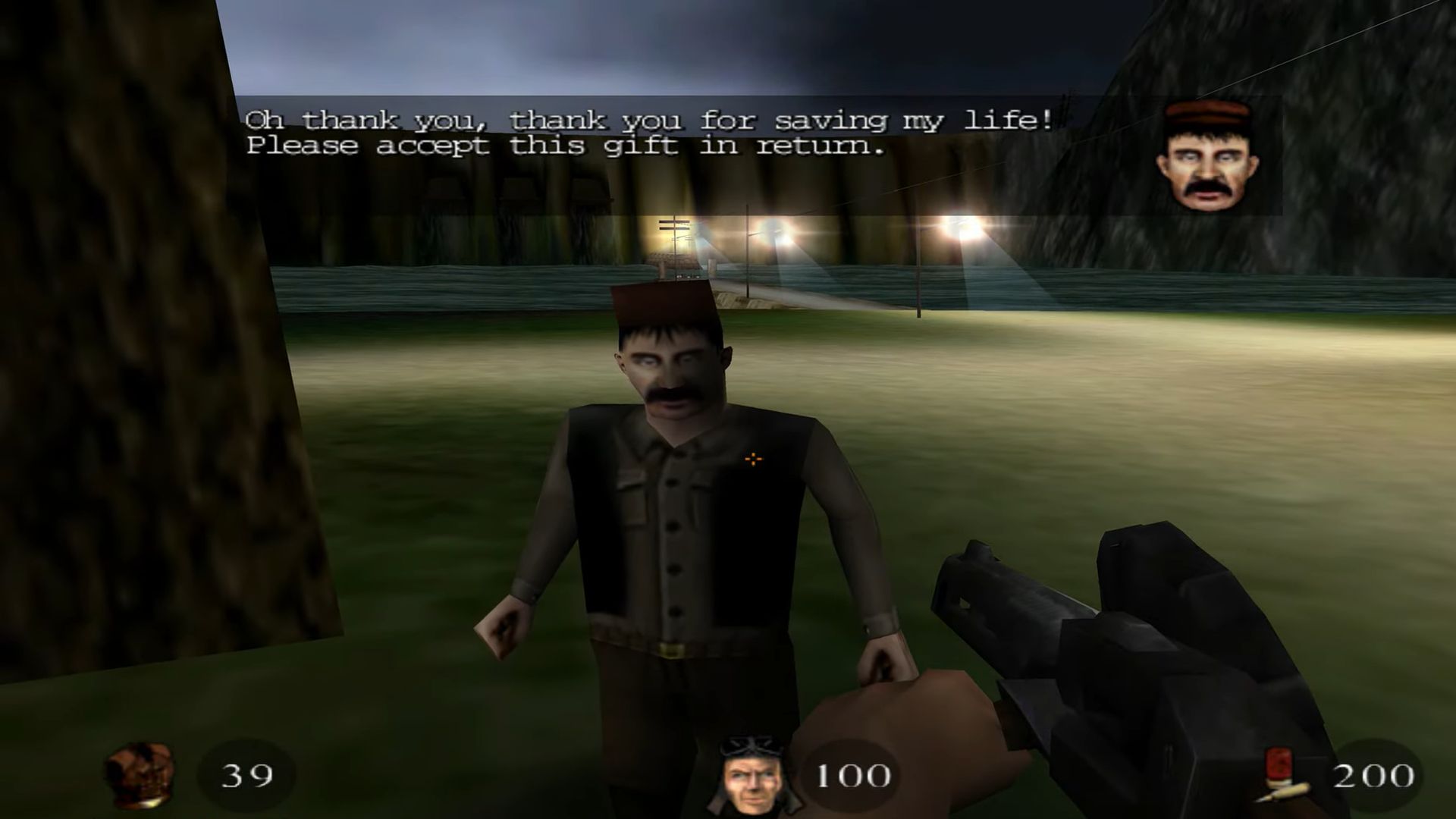

By all accounts, Refraction's singleplayer missions were ambitious yet confusing—mixing outdoor environments with stealth objectives that required Guybrush Threepwood levels of item management. To steal documents from an enemy base, the ideal path was to borrow a uniform as disguise, trade a bottle of vodka for a truck, lift an ID from a crate, and create a fake moustache using cat hair.

OK, so the last one is a lie riffing on a notorious puzzle from Gabriel Knight 3. But you can see why DICE ditched campaign development for Battlefield 1942—beginning a long and uneasy relationship with singleplayer that continues to this day. And you can understand why Wolpaw decided that, ultimately, Codename Eagle was a failed experiment in combining shooting with vehicular freedom.

"It sounds like a great idea in theory and suggests that developer Refraction has created an evolutionary advancement of the first-person shooter," he wrote. "But in practice, Codename Eagle is a short, linear, and really goofy game that's much more frustrating than it is interesting."

Being a fan of Battlefield is still frequently frustrating. But let's be thankful that the story didn't end there, in alternate 1917.

2025 games: This year's upcoming releases

Best PC games: Our all-time favorites

Free PC games: Freebie fest

Best FPS games: Finest gunplay

Best RPGs: Grand adventures

Best co-op games: Better together

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.