Dream Machine 2012: The Future Is Now

2x Dell U3011

Because we need the pixels

We like to play games, hence the presence of quad SLI, but we also edit photos and videos and generally like an abundance of screen real estate. This year, we’re taking it easy with our monitor choice and going with “just” two 30-inch panels—as opposed to last year’s three. That hardly means we’re slumming it, however. In fact, Dell’s U3011 , with its 2560x1600, wide-angle IPS technology, and 1.07-billion-color support is so superb that its $1,400 price seems like a downright steal. Such a steal, in fact, we got two.

Looking Back: The First Dream Machine

The artwork for the original Dream Machine story seems apt—so diminutive are the parts by today’s standards.

It’s always a good idea to occasionally take stock of your life by looking back at where you’ve come from. While it’s easy to take current circumstances for granted, closer reflection can reveal the true magnitude of our progress. We certainly found that to be the case when we looked all the way back to Dream Machine Mk1. Unleashed on the world in September 1996 , the Dream Machine staked out an insane amount of power, storage, and performance.

What made something a Dream in 1996? A 150MHz Pentium processor. That chip ran on a 66MHz bus, was built on a 350nm process, featured a whopping 3.3 million transistors, and contained no cache. That whopping 512KB of pipeline burst cache was mounted on the Supermicro P55-T2S mobo. To keep Windows 95 happy, a whopping 32MB of EDO SIMMs were used for RAM.

The Dream Machine was all about being the best, so EIDE was skipped in favor of an UltraWide SCSI III Quantum Atlas XP3125W drive with 2.1GB of storage. Yes, a $10 USB key has double the storage of the biggest, baddest hard drive you could find in 1996. We suspect that a typical USB key is actually faster than that hard drive, too.

Graphics in Dream Machine Mk1 came from a Matrox Millenium with 4MB of dual-ported WRAM. We paired the Dream Machine with a (then) massive 17-inch Nanao CRT, the ultimate PC display, with 1027x768 resolution and 24-bit color. DM Mk1 also featured a Zip drive, a Moto ISDN modem, a 6.7x Tosh SCSI CD-ROM, as well as an Adaptec 3940UW card and Sound Blaster AWE32 in an ISA slot. Oh, and for the keyboard, a classic IBM PC/AT.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Dream Machine 2012 in Its Element

Does performance even matter? Hells, yeah

Performance. Still. Matters. Don’t let anyone dissuade you from that fact. It’s a core belief we will hold at Maximum PC until they cart us all off to the soylent green factory.

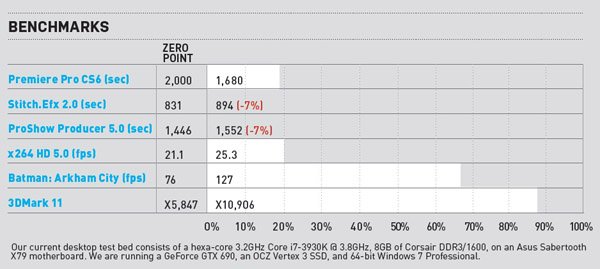

This year’s Dream Machine 2012 lives up to that philosophy: Get the very best you can. But it’s meaningless without valid metrics. To measure how fast Dream Machine 2012 is, we turned to our new stable of benchmarks: Premiere Pro CS6, Stitch.EFx 2.0, ProShow Producer 5.0, x264 HD 5.0, Batman: Arkham City, and 3DMark 11.

When we picked our benchmark suite, we intentionally balanced the applications so as not to unfairly favor highly threaded processors. Yes, some of our benchmarks do take advantage of high-thread-count procs but two don’t, and Dream Machine 2012, despite all its brawn, can’t out-muscle our zero-point, and even the tiny Falcon Tiki (reviewed on page 74), in Stitch.Efx and ProShow Producer 5.0. Producer 5.0 tops out with four cores; after that it’s the CPU’s microarchitecture and clock speed that impact performance. Since Intel has clock-blocked our Xeon E5-2867W, the most speed we could get from the chip was 3.5GHz, with Turbo technically taking it to 3.8GHz under soft loads. With the same essential microarchitecture as Sandy Bridge, the zero-point’s higher base-clock speed of 3.9GHz gave it a slight edge in performance in both Stitch.Efx 2.0 and ProShow Producer 5.0. But as we said earlier, Dream Machine is also about anticipating the future—and the fact is, more and more apps will add support for more cores.

In these scenarios the Dream Machine tells all others to just step the frak back. With our Premiere Pro CS6 benchmark confined to the CPU, the Dream Machine 2012 outran the zero‑point by almost 20 percent. The same happened in the TechARP x264 HD 5.0 benchmark. That’s no slow chip in the zero-point, either. It’s a hexa-core Sandy Bridge-E overclocked to just under 4GHz. Even if we had goosed the SNB-E in the zero‑point another 500MHz (just about the limit for most SNB-E chips) we doubt it would have won.

In gaming the contrast between Dream Machine and the zero‑point was even more stark. Many have wondered if quad SLI scales, and we’re here to say, “Damn straight.” Dream Machine 2012’s graphics performance in Batman: Arkham City gave up 67 percent more frames per second than the zero point and an 87 percent higher score in 3DMark 11. Let’s remind you that our zero‑point features a single GeForce GTX 690—not exactly chopped liver in GPU land. Against a single GeForce GTX 680? It’s like having Thor’s hammer land on your head. We saw a 262 percent speed bump with DM2012 against a stock Ivy Bridge box with a GeForce GTX 680 in Batman and a 176 percent bump in 3DMark 11.

We also wondered if the Dream Machine 2012 offers more where multitasking is concerned, given its 16 threads on tap. For comparison, we took our ProShow Producer 5.0 benchmark and ran it while also running the x264 HD 5.0 benchmark on this month’s stupidly fast and small Falcon Tiki. The Tiki might have managed to spank the Dream Machine 2012 in the tests that don’t stress cores, but multitasking is another story. The Tiki was about 12 percent faster in ProShow Producer 5.0, thanks to its clock advantage and newer Ivy Bridge cores, but when ProShow is run with another task, you better go for a walk or do the laundry. The Dream Machine 2012 completed ProShow in 36 percent less time than the Tiki during multitasking, and it encoded at a 54 percent faster frame rate, too.

If you think these are silly, constructed tests that don’t reflect real-world usage, think back to the days when your single core wasn’t enough, and then your dual-core wasn’t enough. Face it, Skippy, we’re not living in the days when a heavy task was using Netscape and encoding an MP3 at 128Kb/s. Today, your quad might be good enough, but believe us, in the future, even a hexa-core machine will start to feel pokey.

To download the PDF for the Dream Machine 2012 Maximum PC issue, click here .

So that's our Dream Machine for 2012. Were you surprised by our picks? How does your gaming rig stack up? Let us know in the comments section below!

For more video and information on the Dream Machine and the history of the series, click here .