How microtransactions and in-game currencies can be used to launder money

We speak with a cyber security expert about new ways of laundering money online.

When you think of money laundering, it's easy to picture nail salons, shell corporations, or offshore bank accounts. But as new technologies like cryptocurrency are emerging, so too are new methods for turning ill-gotten gains into taxable income. The most obvious methods aren't always the best, though. As bitcoin continues to thrive, policy-makers, police, and prosecutors are investing more resources into combating illegal schemes. In response, there is rising suspicion that enterprising criminals are turning to more innovative solutions, such as laundering money using massively multiplayer games.

During my time reporting and investigating the events of EVE Online, I've stumbled upon my fair share of stories regarding this subject. At first I thought these rumors were nothing more than tinfoil-hat conspiracy theories—a not uncommon thing in a virtual universe many believe is actively run by its own illuminati. A good majority of EVE's players are rightfully convinced that real-money trading—selling in-game currency (ISK) for real money—is a major problem. But others have taken the matter further, claiming that criminals ranging from one-man operations to Russian crime syndicates buy and sell ISK as a way of cleaning dirty money. It sounded absurd at first, but I decided to find out: if this is happening, how would it happen, and is it really that far-fetched?

In the case of online games, there are no anti-money laundering policies or algorithms to detect or prevent strange behavior [beyond the developer's own efforts].

Jean-Loup Richet

Enter Jean-Loup Richet, a Cybersecurity Officer with French telecommunications giant Orange S. A.. As a cybersecurity expert, Richet has worked as an advisor to Europol in addition to being a Research Fellow and Lecturer on cybersecurity strategies at France's ESSEC Business School. In 2013, Richet made waves by publishing a study detailing innovative money laundering methods including those that rely on games like World of Warcraft (Blizzard declined to comment on this story).

To date, there have only been only a few publicized stories connecting money laundering and gold selling, and their details are too dubious to amount to much. Richet believes it's just too niche a method to warrant major investigations with headline-worthy payouts. "There are much easier ways of laundering money. It's innovative and it's kind of safe paradoxically because there are not a lot of officials investigating these cases," Richet tells me. "Most of them are petty criminals—maybe it represents a lot of money as an industry, but the individual operations are small."

I reached out to Richet hoping to better understand the rumors that I had been hearing for years and to speculate further on the subject. In lieu of proper testimonial or actual evidence, Richet would be the closest I could come to discerning if these rumors had any merit. If these people truly existed, who were they, and how often were these criminals exploiting in-game economies to hide the origins of their ill-gotten money? I also wanted Richet's opinion on a hypothesis inspired by a Neal Stephenson novel: Could a videogame developer use fake microtransactions as a way of laundering money?

One man's gold

MMOs like World of Warcraft have historically struggled to contain the now widespread phenomenon of gold selling. Faced with the enormous grind of leveling characters or earning gold, players with little time but plenty of wealth will purchase gold from farmers, typically from China or South America, who have little of either but are more desperate for the latter. It's a practice developers such as Blizzard have worked to stamp out through rigorous monitoring of in-game transactions and new systems like WoW tokens that let players buy gold indirectly from Blizzard.

But as Richet's study suggests, mixed in with usual goldselling transactions is the potential for criminals to launder their money. "It is not a common behavior," Richet says. "But what I found interesting in highlighting this method of laundering [was that] it was more under the radar because nowadays everyone is talking about bitcoin laundering. There are some places where government officials, like Europol or Interpol, are more likely to be [monitoring]. But in the case of online games, there are no anti-money laundering policies or algorithms to detect or prevent strange behavior [beyond the developer's own efforts]."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

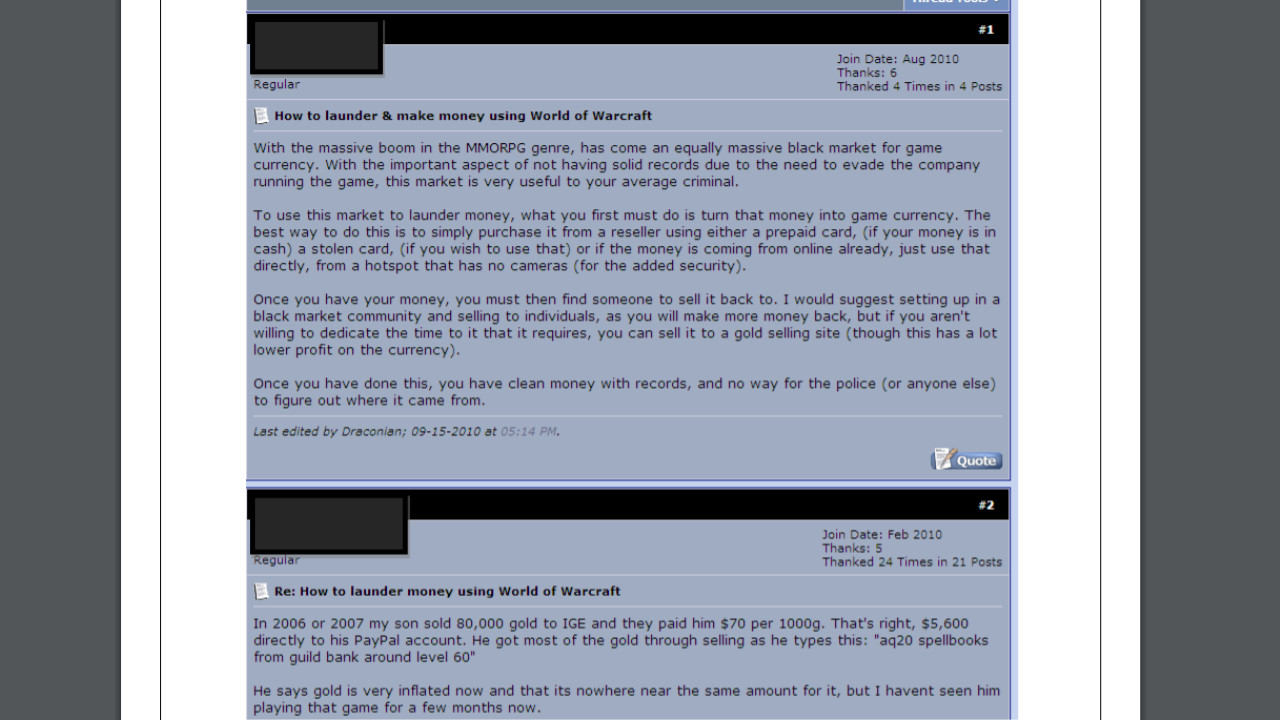

The only problem is there's no real way of knowing how popular this method of laundering may be. The methodology in Richet's study relied on combing through popular hacker and 'blackhat' forums searching for certain key terms. His findings indicated that hackers had, according to their own anonymous testimony, laundered money in this way, but Richet was unable to quantify the behaviour.

On a fundamental level, digital money laundering works similarly to its analog counterpart. The television show Breaking Bad provides an example of a classic money laundering scheme. With millions of dollars of drug money stored in his house, protagonist Walter White purchases a car wash that primarily deals in cash. As he does legitimate business during the day, Walter's wife also rings in fake customers and "pays" with her husband's drug money, turning it into taxable business revenue. Short of a full blown investigation by the IRS, no one would realize that the car wash's revenue is being inflated by Walt's drug money.

The same principle applies online, but cybercriminals make use of "exchangers" and "obfuscators" to hide the trail their money leaves as they transfer it. "Let's say, for instance, that I have stolen a Paypal account and let's say that this Paypal account has about 1,000 euros," Richet says. "The first step is to make things look fuzzy. A hacker will not send the stolen Paypal money directly into his personal bank account. So first, I will forward the amount of this Paypal account to two other fake Paypal accounts that I will create with remote administration tools [software that allows a hacker to control a victim's computer]. This way, it will be more difficult for police officers to investigate this case."

"Then I will use an exchanger and will change the money to any online currency. Depending on my level of paranoia, I might exchange it into bitcoin, and then I might use another exchanger to turn it into World of Warcraft gold coins."

It's difficult to follow the path of money the more steps you add, but you'll also lose more money.

Jean-Loup Richet

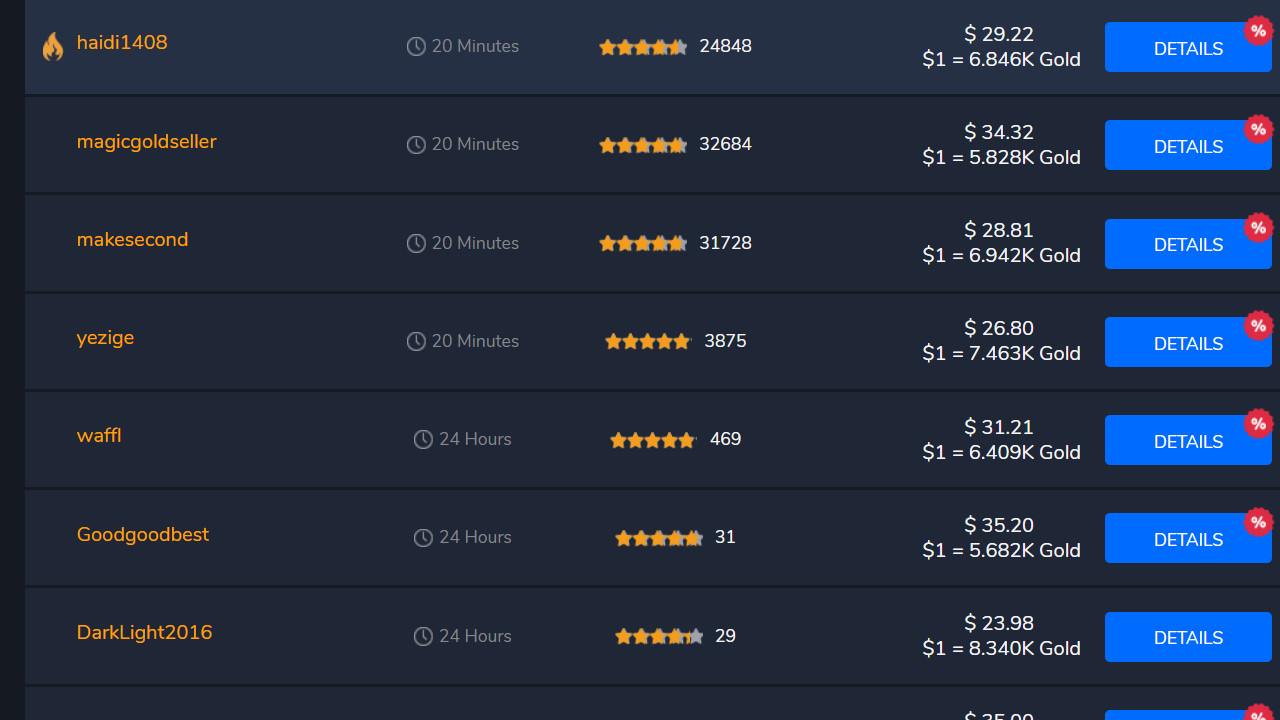

Making use of popular gold selling websites or "exchangers," like this one, the hacker could then buy World of Warcraft gold using their stolen money and either meet the seller in-game or receive an in-game mail with the gold included. The hacker would then turn around and sell their newly bought sum of gold—either for cryptocurrency like bitcoin or, if they choose, using another method. At this point, the origins of their money would be nearly untraceable. "It's difficult to follow the path of money the more steps you add, but you'll also lose more money," Richet says. "Exchangers always take a commission, tenders have commissions. So in the end, the hacker will lose more money with multiple steps, but that's more chances of being undetected."

Even in a hugely popular game like World of Warcraft, Richet tells me that the chances anyone is trying to launder a million dollars are next to none. It's simply too much to move through such an insecure exchanger where a goldseller could rip you off or a developer could catch wind and confiscate your gold. At current exchange rates, even $10,000 USD would represent an astronomical amount of gold.

In the case of EVE Online and the rumors I've been hearing for years, the likelihood of it being an exchanger for launderers is even smaller due to the game's population, which is only a small fraction of Warcraft's. While it makes for a fun theory to whisper about over beers, it's more likely these rumors are simply propaganda meant to tarnish a player's reputation. Yes, someone could launder money through games, and there's some evidence that it's happening, but massive MMO crime rings are likely just fiction.

Laundering through microtransactions

In researching this story, I also became fascinated with the hypothetical idea that a free-to-play game that relied on microtransactions could, like Walter White's car wash, become an exchanger for its owner. Since it's common for criminal organizations to invest in legitimate businesses to clean their money, why not invest in one that sells virtually worthless items (cosmetics, account features, etc.) to an audience that buys them frequently and—in the case of 'whales'—is sometimes expected to spend big? With digital marketplaces like the Apple App store, Steam, and countless platforms bursting with free-to-play games, was the idea really that far-fetched?

The answer is yes, it is far-fetched. But Richet thinks it's possible, too. "It doesn't seem like a mad idea to launder money like that," he tells me. "It is not uncommon for criminal organizations to invest in legitimate businesses, whether it's a game company or a traditional money laundering operation, like for instance a car dealer."

On paper, the idea seems like a money-laundering homerun. A free-to-play game that survives on microtransactions—like Warframe, World of Tanks, or any number of others—has a customer base often makes many purchases over time, eventually spending between hundreds to thousands of dollars. It's the perfect cover.

But there are a ridiculous number of obstacles too. "Everything is recorded," Richet says. "It's not like using one-shot escrow services. In the case of a game company, you build your game and you have a lot of microtransactions and all of those microtransactions have to come from different devices. For example, with the Apple Marketplace, each user has to have an Apple ID that should be linked back to one IP, one MAC address, and so on."

To pull it off, Richet says you'd need a network of botted devices connecting to your game and purchasing microtransactions. And it has to do that in a convincingly human way. And using a third-party platform like Steam or Apple, both of which handle the transactions securely through their own backend, is incredibly risky since they'll have their own methods of monitoring and tracking sales and receipts. "It would be much easier to build their own platform and sell microtransactions directly to consumers," Richet says.

Microtransactions are interesting in that they don't attract a lot of attention, because it's not like receiving a wire transfer for 100,000 dollars.

Jean-Loup Richet

Perhaps the biggest obstacle would be actually having a semi-popular game fueling your money laundering. It would be hard to justify the ongoing success of a game that is cheaply made, poorly reviewed, and overtly exploitive. But one that already has a growing and paying playerbase would be a perfect candidate. Similar to traditional laundering, a car wash with no legitimate customers is going to have a harder time tricking investigators with fake ones. As Richet tells me, "No one suspects a success story."

"It's not like you're investing in a traditional laundering scheme, which looks suspicious," Richet says. "You're investing in a game company. It looks legitimate at first glance. Microtransactions are interesting in that they don't attract a lot of attention, because it's not like receiving a wire transfer for 100,000 dollars. It's five dollars plus five dollars plus five dollars. It doesn't set off alarms like a large wire transfer. It might be easier to cover the traces of money that way."

At the same time, that means either convincing a game developer to become a puppet for a criminal organization or building one from the ground up—neither of which seem like particularly easy tasks.

Still, it is possible. Bitcoin had a significant impact on how criminals do their business online, but there are always those looking to invent new methods for keeping authorities off their trail. As virtual in-game economies grow, so too will opportunities to exploit them.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.