What a Myst and Riven superfan thinks of Obduction

As the spiritual successor to Myst and Riven proves, sometimes you really can go home again.

My friend Jeremy Nissen doesn’t play games the same way I play games. When he really likes a game he takes it apart piece by piece, masters it, and for fun completes feats of skill I find unimaginable. He taught me how to play NetHack, one of PC gaming’s most notoriously difficult roguelikes, in a video series we did together. He’s beaten NetHack countless times. Same with the Dark Souls games, which he runs through at level one just for kicks. He and his wife beat the PS4 Souls offshoot Bloodborne each holding one half of the controller.

As if those displays of dexterity weren’t enough, one of his favorite games of all time is Riven, the 1997 sequel to Myst that I found impossibly opaque. Jeremy raves about Riven (which, of course, he’s finished three times), so I thought of him as the release of Cyan Worlds’ Obduction approached last week.

What did the biggest Riven fan I know think of the successor to a game he loved? By the end of the weekend he’d cruised through Obduction twice and had, well, a few things to say about how it lives up to Riven’s legacy. The good news: for the most part, it really does.

“As far as Myst and Riven go, a lot of people like Myst better, but to me Riven is the quintessential experience,” Jeremy told me over Skype. While Myst “was a really cool proof of concept,” he said, Riven “takes what is essentially a puzzle game at its core but … when you actually feel immersed in the world, you don't feel like you're solving puzzles as much as you feel like you're figuring out a world that wasn't designed as a videogame. It feels [more like] a world that makes some weird kind of sense, that's not what you're used to, and you're just figuring things out.”

Jeremy said that the powerful feeling of place he thought Riven got so right did have its ups and downs. Some puzzles felt more videogamey, while others naturally blended into the logic of the world. But as a whole, Riven’s utterly alien, mysterious setting just clicked with him in a way that no other world has managed to do so convincingly.

“It’s such a cool feeling,” he added. “It's also a ridiculously hard game, and I don't know how much of that is intentional, and how much the development effort got out of hand. It might've been a weird perfect storm thing, where some of it is even accidental.”

When Cyan Worlds launched its Kickstarter for Obduction in 2013, Jeremy backed the project but tried to keep his excitement in check. And three years later, here it was.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“I didn't have confidence, even in Robyn and Rand, to create something that quite did for me what Riven has done,” he told me. “I was really pleasantly surprised, especially out of the gate. I think they were already good at coming up with interesting worlds to explore, they've been on point with that since the early days, but the one thing they've really gotten good at now is just game design. They really guide you very nicely into the mindset that you need to be in for the game. It's a lot easier because of that, to begin with, but it's a more normal videogame learning experience to get up to speed with it. It felt more natural.”

"I didn't have confidence, even in Robyn and Rand, to create something that quite did for me what Riven has done."

Jeremy called out the opening hours of Obduction as the cleanest experience Cyan has made: there’s a character who gives you some high-level direction and goals to pursue, but it’s still up to you to find your way to those goals.

It’s open-ended enough to let you wander between puzzles, but not so big that you’ll get lost wandering as you would in Riven. The late game, he said, ended up a little less interesting. “It’s a more linear experience … There were a few stretches where I didn't feel like I had to use my brain. Just do whatever the next thing you can do is, and keep doing that, until you win.”

His favorite addition to Obduction was a camera, which allows you to take photos to reference later, a great help for puzzle solving and documenting potential clues. Obduction also brought back a similar take on a puzzle that Jeremy loved in Riven, though this time around he thought it fell short of the original.

There’s one puzzle in Riven he loves to talk about as “a perfect example of what made that game what it was.” A ways into the game you find your way into a children’s classroom, and by fiddling with one item on the shelf, you can learn how to count in Riven’s number system. You learn to count by playing with a child’s toy. It feels real, not like a puzzle.

And the equivalent in Obduction?

“They took the approach of having more things literally written out for you,” he said. “It's a straight up school worksheet for how to read and write this number system, complete with bullet points that described it. I thought that was so excessive. For instance, the number system in Obduction is a base four number system, and there's literally a bullet point that says it's base four. The Riven system was base five, but when I was a child, even if you told me what base five was I wouldn't have known what that meant. But I was still able to figure out the symbols based on their visual components, and ‘okay, when it goes to this number of symbols it wraps over and starts repeating.’ Those are so excessive. You don't need to tell somebody it's a base four system. They can figure it out if they mess around enough.”

On top of that over-explaining, there’s also a device to help you count and learn the number system. He pointed out that you could just come back to that station, again and again, without really learning how the numbers work.

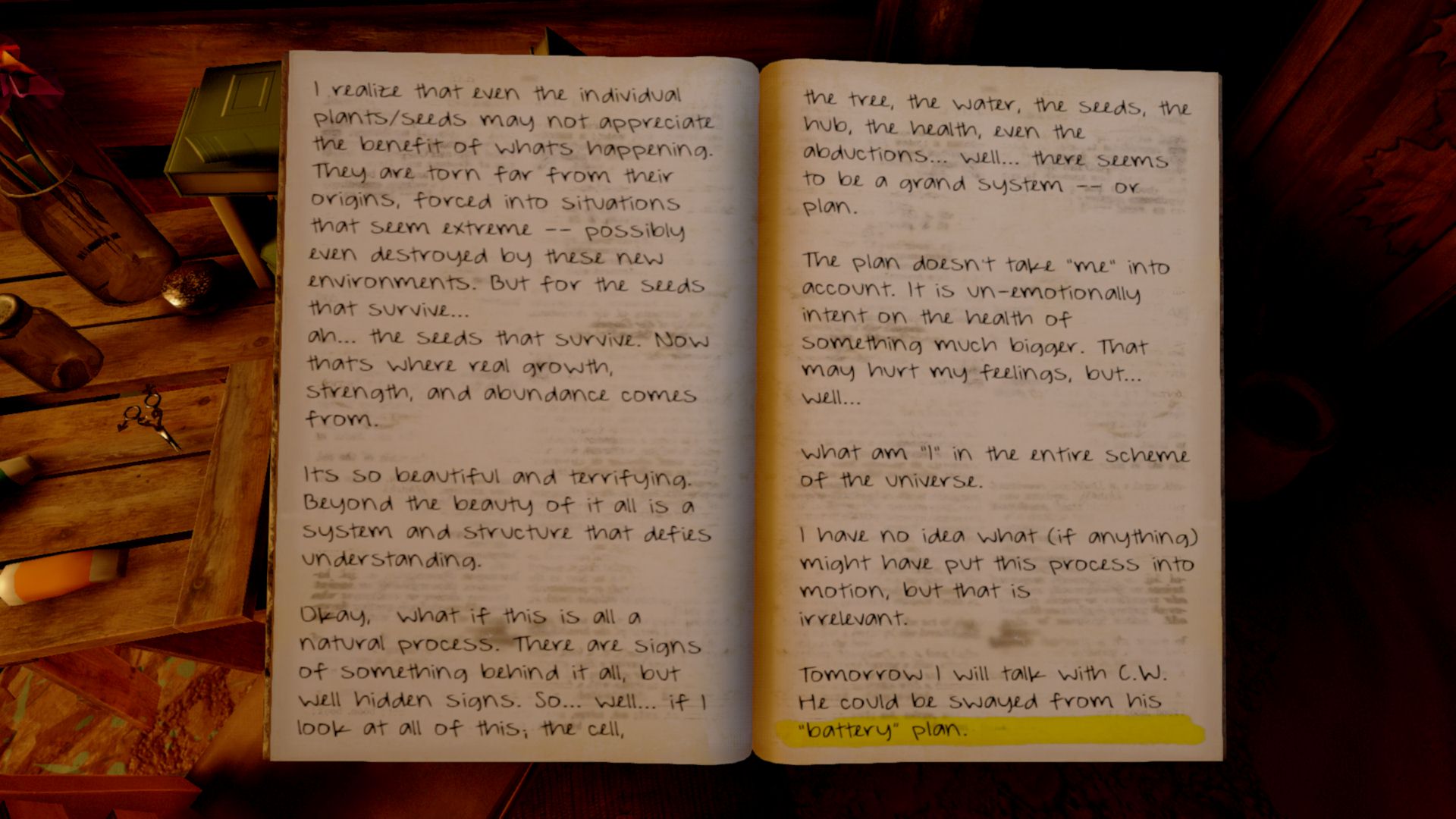

The clues found in books scattered around the world are similarly in-your-face, too. “When you find a book with 3-4 pages you can read, the clue is actually highlighted or a different color, which I thought was so excessive,” Jeremy said. “It felt like I turned on easy mode, like ‘here's the clue, moron! It's highlighted in blue.’ I thought that was really silly. That's one of the things that really takes you out of it. It immediately reminds you that you're playing a videogame: this is not a natural occurrence.”

‘Easy mode,’ to him, is no doubt welcome relief to some players who found games like Riven impenetrable. And while real difficulty settings may not be in the spirit of the adventure games Cyan Worlds makes, it’s easy to imagine a tweaked version of Obduction that hides those more blatant clues and reworks a few that ended up being “just a pointer to the answer, rather than being a clue,” Jeremy said.

Perhaps there's a patch for Obduction's most hardcore players in its future. But even if Obduction left Jeremy hoping for more of a challenge—he doesn't think he'll be playing it a dozen times, as he has with Riven—it still managed to capture that old Myst magic.

To Myst and back again

Talking to Jeremy about Myst and Riven reminded me that as influential as those games were, there’s really been almost nothing like them in gaming for years. They were puzzle games as much about atmosphere and discovery as they were puzzles. Myst helped usher in the use of the CD-ROM and pre-rendered graphics (and it's both loved and hated for the trends it set in motion). Once that novelty faded in the 2000s, who was making games with the scope and mystery of Riven? The closest analogues may be games like Dear Esther or Gone Home or The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, which prioritize story and environment over puzzles.

The point is, most of the puzzle games that followed Riven since 1997 actually misunderstood what it was that fans like Jeremy really loved about the game. Puzzles were important, but a cohesive sense of place for those puzzles to exist in? That mattered more. How fitting that Cyan, 20 years later, would be the ones to come back and do it right.

Check back tomorrow for our own review of Obduction.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).