The Orange Box review

Our original Portal, Team Fortress 2 and Half-Life 2: Episode Two reviews from 2007.

Our other anniversary pieces:

- Valve interview

- Remembering HL2: Episode 2

- How TF2 changed FPSes

- Portal and the cake meme

To celebrate 10 years of the Orange Box, we're publishing the original PC Gamer reviews from our archives. All three games were reviewed by Tom Francis in issue 180 of the magazine. The reviews capture our excitement at the release of a bundle containing three 90+ rated games. October 2007 was a great month for PC games.

Half-Life 2: Episode Two review

Last night I had a really weird dream. I dreamt that instead of ending where it ended, Half-Life 2 just carried on after the explosion at the top of the Citadel. Vortigaunts rescued me, then Alyx hugged me, and I ended up catching a train out of town into a countryside full of tiny Striders. Then a Combine Advisor made me do my uni finals all over again, only this time I hadn’t revised and the papers were all in Chinese. And I was naked.

It’s surreal that Valve are still churning out more Half-Life 2, three years on. As beautifully crafted as Episode One was, it did tread on a lot of its parent’s toes. Episode Two certainly doesn’t do that. It turbos away from them at 90 miles an hour in a customised Dodge Charger, with Alyx riding shotgun.

I won’t spoil any details, but Ep2 is what happens after you and Alyx break free of City 17 once and for all. The setting for most of your previous adventures is nothing more than a smouldering scar on Episode Two’s skyline, and the Citadel looks like a longfinished game of girder-Jenga. Because of that, and because you spend a lot of time driving a car that could have swerved straight off the set of a postapocalyptic Dukes of Hazzard, Ep2 feels wild, dangerous and cool.

Your time—a little under five hours—is diced into refreshingly different sections. Valve still do pacing better than anyone. They break fights with puzzles, driving with combat, solitude with friendly faces and claustrophobic tunnelrunning with epic, sweeping vistas of naturalistic landscape.

These make Ep2 feel huge. It only took me an hour longer than Episode One, but every inch of it is gorgeous uncharted territory, and there are more inches than the running time suggests. Spending a third of the episode in a supercharged two-seater means covering a lot of ground, of course, but it’s more than that. There’s an openness to a lot of Episode Two’s chilly forested landscapes that’s new to Half-Life.

Even the shotgun is newly beautiful, gleaming ominously in the sun with a convincingly weighty gunmetal sheen.

It’s all the more inviting because Episode Two is the most sumptuous chapter of the Half-Life saga, and by a country mile. It’s as if Valve’s tech and art teams are trying to outdo each other: the Source engine has had a striking technical overhaul that renders textures, materials and curves uncannily well, and the artists clearly relish having a fresh palette to work with.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Towering conifers bristle gently in the breeze, casting soft shadows across winding mountain paths. Each toothy vortigaunt’s big peering eye glints glassily, a perfect ruby sunk into finely wrinkled brown skin. Even the shotgun is newly beautiful, gleaming ominously in the sun with a convincingly weighty gunmetal sheen. We get to see the pine-covered rocky land of this nameless nation, and it conforms to no established gameenvironment stereotype. It resembles only the real world—some proud, cold country I feel sure I’ve been to—and it has that authentic real-world grubbiness that only Valve have figured out how to recreate.

The combat explodes across this soothing canvas with a brilliantly messy splat. Something clever involving particle physics has allowed Valve to make thick black blood, lurid yellow goo and something a lot like vomit spray repulsively from your victims with every cracking impact. The new poisonous Worker Antlions burst like bioluminescent bombs; injured Hunters drool a sticky slurry of their own innards from where their mouth should be; and when the vortigaunts fight... Jesus God. The trailers released last year showed nothing of this—some consolation for those of us who spoiled big chunks of the game for ourselves by watching them.

The three-legged Hunter creatures are the highlight of the fighting: velociraptors to the Strider’s T-rex. They’re the perfect size for Gordon-killing: compact enough to chase you indoors but hefty enough to take the shotgun blast that awaits them there. More importantly, they’re bright enough to do so when you least expect it. Valve have trained them to deduce where you’re heading and get there first by a different route, and the effect is alarming.

They’re another departure from what we’ve previously been shown of the game: they used to fire a tiresomely familiar pulserifle burst, now they fling a torrent of bulbous azure darts on swirling trails. These thud into whatever they hit, quiver pregnantly for a moment, then detonate in a flurry of fizzling plasma pops. Cover is no longer enough: wherever you hide, in a few seconds you’re going to have to throw yourself from the room before it explodes.

Once they’ve flushed you out with their flechettes, the Hunters use Episode Two’s wide open spaces to take a scampering runup and smack you into the stratosphere. The seemingly generic name is exactly apt: they take the initiative in combat, and nowhere is entirely safe. The Hunters continually provoke and surprise you in ways that Half-Life hasn’t since the first game’s marines.

The sense of threat is a prevailing and escalating theme As you can see, the pistol has been beefed up a little. Once, just once, itd be nice to have a windscreen. This is what Vorts do to Antlions. of Episode Two, and it extends to the plot. You and your friends are trapped, maimed and violated in ways that are distressing on a really visceral level, and it’s properly gruesome to watch. The blood-soaked tone gives the story a force that makes it the darkest and most exhilarating chapter yet. It’s Half-Life’s Empire Strikes Back—and it even has a less snowy analogue to the Battle of Hoth.

That fight needs to be mentioned—but mustn’t be described—because it’s the first truly satisfying climax to a Half- Life game. Half-Life’s Xen was disastrous, shunting energy balls at a bigger energy ball in HL2 was uninspired, and taking down a single Strider with the RPG at the end of Ep1 was almost comically banal. But at last Valve have crafted a finale worthy of the adventure that precedes it, and the result is the largest, most open-ended and complex battle of the series. It’s also one of my favourite Half-Life moments so far, and that’s saying a lot.

Episode One seems dismally small and boring by comparison, however much I loved it at the time.

Episode Two is, needless to say, so polished that it hurts to look directly at it in sunlight—so my only criticisms are pretty feeble. The first is that it’s slightly too easy, right to the end. I wouldn’t mind if Hard mode only increased the damage you took. But it also reduces the damage you deal, and that renders almost all the game’s weapons meek and unsatisfying. Speaking of which, we still haven’t had a single new gun since the end of Half-Life 2. That game never went nine hours without introducing several new weapons, so where are our shiny new deathsticks? The armament is the only part of the Half-Life formula that’s starting to go stale.

Episode One seems dismally small and boring by comparison, however much I loved it at the time. But the one edge it does retain over the second is Alyx: she’s not quite as charming here. There are a few really wonderful character moments with her, and one superb performance from actress Merle Dandridge, but nothing quite as heart-meltingly cute as Episode One’s Zombine joke. To be fair, that’s only because the grim plot mostly keeps her in her less convincing :o and :( emotional states.

Still, I didn’t think it was possible for a mere episode to surprise, excite and energise me as much as it has. The simultaneous global unlocking of the next chapter of Half-Life is becoming one of the most geekily enjoyable events on the gaming calendar, even with the mortifying suspense of relying on Steam under heavy load. Not just the playing, but IMing inanities to friends while it unlocks with an agonising slowness, and retiring exhaustedly to the nearest forum afterwards to exchange breathless superlatives. “Oh, and the bit where—and then she—and the Advisors!”

Half-Life 2’s critics groan about its linearity, and its fans groan about how long it is between episodes. But the series shrugs off both complaints when you start seeing it for what it is: a series of playable movies. Better than anyone, Valve make cinema that you’re a part of—and they do it at about the same rate Warner Bros churn out new Harry Potter films.

In Half-Life’s day, it was a compliment to say a game felt like a Hollywood movie. In the intervening years Valve have become more professional and accomplished than any visual effects studio working in Tinseltown, and now it would be an insult to liken one of their beautifully crafted works to the messy dross the American film industry churns out.

I know some gamers love a sandbox—I’m one of them—but it always baffles me when that love seems to preclude the enjoyment of anything else. Do these people storm out of cinemas when they realise their popcorn munching isn’t controlling the actors? Are there really people who can’t enjoy a gorgeous, hurtling ride like this? That would be sad, because they’re getting seriously good. Bring on the third.

Verdict Fresh and thrillingly dark

Score 93

Team Fortress 2 review

Last night I had a really weird dream. I dreamt that Valve were finally going to bring out Team Fortress 2, only they’d made it look like some crazy Pixar cartoon, it was budget-priced, and all the classes talked as you played. And I was naked.

But here we are. This is the trouble with a dream job: you have to do it even when you’re asleep. I’m just going to review this ridiculous ‘Team Fortress 2’ fantasy until I finally wake up and discover that I am, after all, a chartered accountant.

Let’s not dwell too much on the original mod for Quake and Half-Life—that was ten years ago, not everyone played it, and TF2 is very obviously aimed at new players as much as old. Worth mentioning, quickly, is that it’s got the same nine classes but fewer weapons for each, grenades have been removed entirely (thank God) and, well... look at it. Look what they did to it.

The changes might sound like simplification, but like the art style it’s more about exaggeration. The Spy used to have a double-barrelled shotgun, for goodness’ sake. Taking stuff like that out hasn’t made it a simpler game, it’s made the choice to be a Spy a more meaningful one. Every class is so tightly focused on doing its thing that TF2 feels like nine different games fighting each other. That’s bewildering at first, but it’s a joy to watch characters this beautiful smash each other to pieces while you learn.

That Pixar comparison isn’t fair. TF2’s gurning murderers look better. Valve have remodelled their class-based multiplayer FPS after the work of turn-of-the-last-century illustrator JC Leyendecker. Google Image him and you’ll see the similarities in the angular, characterful silhouettes. They’re a world away from the lumpy sacks that were The Incredibles, and as it turns out, class-based multiplayer combat has long needed that distinctiveness.

It sounds like a small thing, to be able to tell what class someone is as surely and as clearly as you can see them at all. To have an immediate sense of the heft and power of a Heavy, rather than an abstract notion of his hitpoints. But stuff like this has an intensifying effect on your moment-to-moment experience: you feel, see and comprehend the game world in Technicolor. It makes all the relationships instantly clear and the importance of your actions explicit. In short, it makes everything you do 300% cooler.

That’s Team Fortress 2: multiplayer magnified. Cooperation means more, victory is sweeter, betrayal is more bitter, defeat more humiliating. But it’s what lies at the heart of multiplayer gaming that matters most, and that is, in the parlance of our times, the lols.

The image of a Scout circle-strafing a Heavy quickly enough to smack him into a stupor with a tiny baseball bat is inherently funny. But it only really gets a belly-laugh when the Scout is a scampering stickboy in knee-high socks, and his victim a meat-headed brickheap of a man. Character is a catalyst for comedy, and until now multiplayer games just haven’t had it. They were already funny, but TF2 just brings it out beautifully, every round.

All that stuff—gloating, humiliation, snuff slapstick—is best with friends. But another of TF2’s charms is that you form relationships with the people you’re playing with so quickly. They might not be friendships exactly, but they add an edge of human interest to every interaction. I don’t know Gabe Newell very well, but after he’d followed me around as my personal Medic for a while, I felt like I did. The same goes for Robin Walker after he and I—as Engineers—constructed an elaborate ecosystem of killing machines that reaped dozens of enemy lives.

I don’t know Gabe Newell very well, but after he’d followed me around as my personal Medic for a while, I felt like I did.

That’s a quirk of the way friendly classes tessellate, but TF2 is more interested in playing up your relationship with players on the enemy team. Each time you die the game freeze-frames on your killer after a short delay, and that delay is calculated very cynically to catch him in the middle of an offensive taunt animation. Worse, the game then invites you to save this lewd image of your murderer for posterity. And the game looks so damnably good that you’re usually compelled to do it.

Valve know we like to mock the dead, dance on graves, hump corpses. So as well as making that mockery more crushing, they’ve also made a game of it: taunting now roots you to the spot, pulls you out into third-person view to watch yourself swagger, leaving you utterly helpless. You’ve actually got to make a strategic decision about whether you’ve got a few seconds to play air guitar on your victim’s carcass or not. I’ve seen chain-reactions of death where a Sniper waves to his unfortunate victim, is shot dead mid-mock by another, who then performs the same taunt—with the same fatal result.

The taunts, and the lines uttered alongside them, are part of the persona Valve have given each class. If you’ve seen the Meet The Heavy or Soldier trailers, you’ve had a taste of this. (See the disc for the most recent.) But the idea that your character is a character, with his own personality, is only as relevant as you make it. If you leave the taunt and chat commands alone, you’ll only really hear yourself if you’re a Heavy: the big guy can’t resist cackling deliriously if you’re getting a lot of kills, and an extraordinary spree will usually be punctuated with a bellowing “SO... MUCH... BLOOD!”

The other classes’ involuntary comments are too quiet and infrequent to hear often, but in a quiet moment I did hear the liquor-chugging Demoman mutter that “On the plus side, I already don’t remember this.” If, like me, you develop a particular fondness for one character, you can hammer the chat shortcuts and taunts to mutter battlecries at every opportunity. It was the gasmasked Pyro I fell in love with, and if you’re wondering what his voice is like, the answer is a punchline in itself: muffled.

His battle-cry is “Mmmph mm mumph umph!” and his call for a medic is “Mmphumph!” His dumpy teardrop physique, shrew-like tiny head, waddling gait and baggy, flame-retardant suit—they all evoke an endearingly downtrodden man. So I run everywhere garbling incomprehensible insults, rocking out on my fireaxe over my crispy fallen foes, and waving my bent petrol-pump flamethrower exultantly over my head after every match; win or lose. “Mmmph mm mumph umph!”

Most maps kick off with the two teams separated by a metal mesh that lifts after a minute, giving Engineers time to build their defences and everyone else a chance to taunt each other. The result is two rows of people jeering, singing, laughing, braying, dancing and whooping at each other in a cacophony of clashing voices. It’s a long-needed outlet for our natural tendency to pre-game smack talk, and it makes the atmosphere of the calm before the storm electric.

TF2 comes with six maps; three are new, three are remakes. The roster doesn’t feel slim once you play them. Hydro, a control-point map split into six zones, restructures itself between rounds to put teams into one of 16 different configurations. The others are mostly a linear series of control points—all except Gravelpit, which gives attackers a choice of two to assault, and 2Fort, which remains stubbornly Capture The Flag. Capture The Intelligence, sorry.

All are heartbreakingly gorgeous. The soft lines, gentle shading, warm palettes and wonky edges set off the gaudy action magnificently. It’s tempting to pussyfoot around with weasel words such as ‘among’, ‘could be’ and ‘in years’, but screw it. Team Fortress 2 is the most beautiful game ever made. I say that as a man who’s seen Crysis running on maximum settings, and I’m not kidding or exaggerating or on any more than the usual amount of drugs. Sorry about that, every other videogame artist in the world. This was not your lifetime.

Granary and Well are a little straightforward flow-wise, but TF2 sometimes benefits from a simpler arena. A linear series of control points might not sound like a lot of fun, but the simplicity shifts the focus to tactics and clever use of classes. My team won a round when another player crept behind the enemy lines to camp their locked-off control point, capturing it the moment it came into play. This despite the fact that he—presumably inadvertently—announced his plan to the entire enemy team by using ‘say’ instead of ‘team say’. The post-game chat revealed that they didn’t take it well:

EricS: We’re actually going to have to erect flood barriers from all the QQing going on over here.

Finole: I need a raft.

Robin of Death: Driller’s quit FPSs.

Robin of Death: And the company.

Gravelpit is a more interesting equation: the defending team has to guess which of three tall towers the attacking team is going to gun for first. Dustbowl, meanwhile, is sure to be a cult favourite all over again: it retains the deafeningly chaotic opening, the succession of increasingly bloody chokepoints and the desperate last stand. 2Fort is faithful to the classic original in all but appearance, and makes a particularly rich playground for the more tightly focused classes.

Hydro’s more like a set of maps than a single arena, and feels a little arbitrary for it. Valve have made it this way to keep it fresh, but I’m not sure multiplayer maps need to be fresh. CS’s de_dust is great partly because we all know it so well—so is 2Fort, for that matter. Hydro’s hypermagical rejiggling just extends the period for which you’re not really sure where you’re going. We won’t know for months whether it was worth this to keep mixing things up, and I’m happy to bear with Valve’s experiment for now—some parts of Hydro are superb.

The initial confusion of Hydro does highlight a real shortcoming of TF2, though: no minimap. Only the most co-ordinated, voice-communicating hardcore clan has any useful notion of where their team-mates are. In a game where the nine different classes are so interdependent, it’s vital to know where your turrets are set up, whether there’s a Medic nearby, and if the Heavy cavalry is on its way. Valve’s logic in omitting it is that some players never use them. Fine for those guys, but there’s no substitute for the rest of us to knowing where our team is without having to ask everyone all the time.

Mind you, a minimap would make the Spy’s life harder. He was always Team Fortress’s most inventive class, but his new incarnation is even more extraordinary. He can disguise himself impeccably as any class of enemy, and now he can also render himself temporarily invisible to slip into their base. There’s no friendly fire in TF2, but shooting all your team-mates to uncover Spies wastes too much time and ammo to be practical.

As a Spy in disguise you still take damage from enemies, but you’re man enough not to show it—you don’t bleed. That gives rise to a hilarious mindgame: a good Spy will take a near-lethal shotgun blast to the face from a supposed friend without flinching, confront his attacker toe-to-toe as if to say “What?”, and continue his infiltration beyond suspicion.

The Spy’s disguise-o-meter, built into his cigarette case, will give him the name of an enemy who really is the class he’s pretending to be. That means that every now and then, you experience the alarming existential crisis of encountering someone with your own name. Realising they must be an enemy Spy, you declare to your team that “The Spy’s a Soldier!” Whereupon, of course, everyone empties their magazines into you.

If you can stay away from your namesake and take the Spy hunter’s check-shots unflinchingly, the challenge becomes to act like an enemy. I like to dress up as a Heavy, because his reassuringly enormous size makes it hard for anyone to believe he could be a slinky Spy in disguise. It also means you get healed by enemy Medics—a peculiar sensation—and that can lead to an utterly bizarre psychological dance.

The Spy, you see, needs to get behind his victim for a one-hitkill backstab. The Medic, meanwhile, should always stay behind a Heavy for protection while he heals. So the two of you run in circles trying to get behind each other, until the Medic realises—with an almost visible pang of horror—who you really are. He draws his bonesaw, you draw your butterfly knife, and the duel commences. It’s sublime. The knife-edge between the thrill of deception and the shame of discovery makes playing a Spy more tense and thrilling than any other multiplayer experience—even the original TF’s Spy.

The other class highlights are more obvious: shredding a dozen enemies as a Medic-boosted Heavy, bolting past a superior force as a Scout with the briefcase in 2Fort, and detonating enough pipe bombs as a Demoman to fill the room with blood—and the screen with kill reports. In fact, the only class that doesn’t excite is the Medic. His contribution is to heal the major players while they charge in, but he can’t do anything else while he heals so his whole life is just holding down fire. When he’s healed a thousand or so points, he can temporarily make himself and his mark invulnerable, at which point he has to... keep holding down fire. It’s so cruel that he doesn’t get to let rip after all that joyless service to his team.

I have to admit that this, and the minimap problem, bothered me less and less the more I played. Team Fortress 2’s friendly look hides what’s still a dauntingly intricate game, and when you’re still learning the ropes, and the maps, its few flaws seem exasperating. But the measure of a multiplayer game is how much you want to go back to it. Right now I’m quivering a little, and last night I dreamt about it, so yeah. Team Fortress 2 is a bit special.

Verdict Rich, gorgeous and endlessly fun.

Score 94

Portal review

Last night I had a really weird dream. I dreamt that the students who made Narbacular Drop, the space-bending indie game I played last year, had been hired by Valve to make a beautiful new version in the Half-Life universe. You played this wide-eyed girl with strange metal braces on her shins like Eli Vance’s prosthetic leg, and a droning robotic voice kept saying sinister things that I found incredibly funny. Also my Year Nine maths teacher was there. And I was naked.

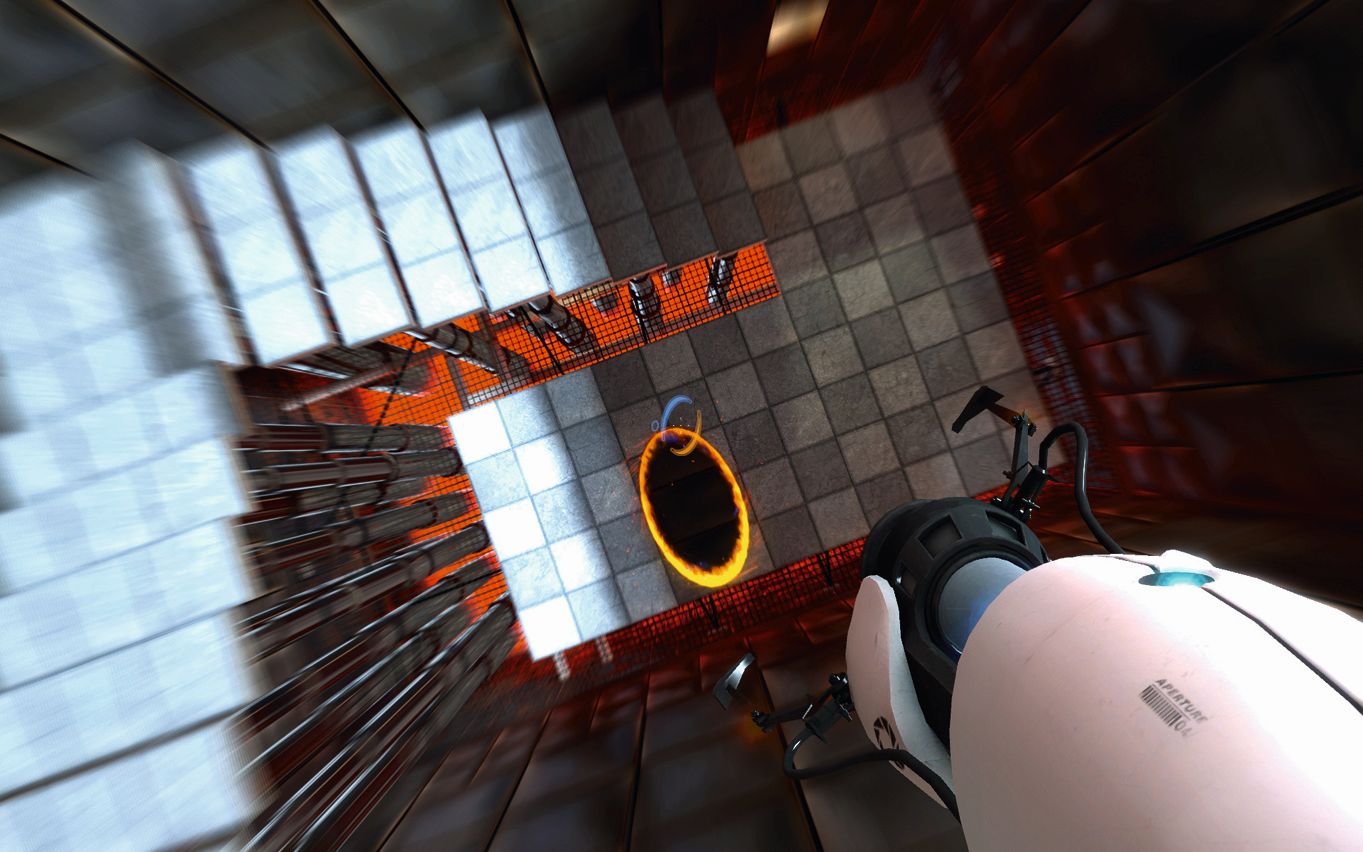

But you’re probably here to read about Portal, Valve’s first-person puzzle game about opening rifts in space to cross uncrossable obstacle courses. It’s designed around one simple but mindexpanding idea: you can shoot a hole in any wall, and then another one somewhere else, and if you walk into one you’ll come out of the other. Fire them side by side and you’ll walk straight back into the room you just left. Fire them on floor and ceiling and you’ll fall through the same room at terminal velocity forever.

The Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device (let’s face it, the portal gun) is your only weapon, but its brazenly impossible uses are endlessly fascinating to perform. The internal logic is flawless, but you somehow never grasp it entirely however hungrily your brain gropes. It is, I’m just starting to realise, abstractly kinky. Portal, honey, how can your physics be wrong when they feel so right?

The game grips you by the wrist and leads you briskly past the befuddling basics of these rifts, straight to the good stuff. Within a few short levels you’re using orthogonal portals to translate your gravitational potential into lateral velocity and flinging yourself exhilaratingly over turrets and lethal slime. By nudging you gently through rooms that cleverly lead your eye to the correct—yet patently impossible—solution, it swiftly teaches you a dazzling roster of lunatic tricks.

Portal is a magnificent puzzle game. The titillating wrongness of every solution and the wonky thinking required to get there make you feel like a space-folding genius, and yet you’ll almost never get stuck. Soon you’ve learnt so many weird ways of perverting the forces and spaces in any room that you can throw yourself through them, like a futuristic Prince of Persia with abilities more improbable and wondrous by far.

The solutions eventually become more gymnastic—opening new portals mid-fling and plummeting back through those you’ve previously opened with pinpoint precision. But by then you’re ready, and performing deliciously counter-logical mental inversions at breakneck speed is something to be relished.

The writing is effortlessly sharp throughout, and with its single inhuman character Portal taps a thick vein of black, absurdist humour that becomes the game’s propulsive force.

The atmosphere, meanwhile, grows thickly sinister. Your singsong robot guide GLaDOS (you’ll find out what it stands for) doesn’t seem unduly invested in keeping you alive. Soon her own delusions creep into her instructions to you. “The weighted companion cube,” she announces as you snatch up a box, “will not threaten to stab you and cannot, in fact, talk. If the weighted companion cube does talk, the Enrichment Centre urges you to disregard its advice.” But as her coldly voiced lines become more murderous and surreal, they also get funnier. The writing is effortlessly sharp throughout, and with its single inhuman character Portal taps a thick vein of black, absurdist humour that becomes the game’s propulsive force. You’ll play faster just to hear the next beautifully unhinged line.

The game escalates magnificently. The puzzles change nature, requiring your to beat the system with the tricks it taught you rather than jumping through hoops. And at the same time, the humour reaches fever pitch—GLaDOS becomes so brilliantly deranged that at times it’s hard to control yourself for laughing. The final flourish—the most inspired credits sequence I’ve ever seen—reduced me to a convulsively cackling wreck, insensible and almost in tears. This is the funniest game I’ve played since Psychonauts.

Sadly, Portal is as short as it is sweet. It took me—admittedly a Narbacular Drop veteran, international super-agent and one of the greatest minds of our time—a little under two and a half hours. That’s long enough for the story it tells, and it tells it well, but it’s so damnably good that the craving sets in as soon as the satisfaction fades.

Depending on gamer demand, Valve say they’ll opt next for a straight sequel, a closer tie-in to the Half-Life games or some form of multiplayer. I just want more GLaDOS. Her lilting, darkly comic words of lethally unhelpful advice deserve a place in the annals of scary robo-speak, right beside “I can’t do that, Dave” and “L-look at you, hacker.”

“If you begin to feel lightheaded from thirst,” GLaDOS chirps, “feel free to pass out.”

Verdict Brain-melting offbeat genius.

Score 92