The nostalgic joy of '90s style PC game installers

Creative installer animations made the wait worthwhile.

Today, game installation is simply the final, invisible phase of a Steam download. Once though, it was a ceremony. Back in the multimedia age—or, less fancifully, the ‘90s—developers treated installers as the front door to their game. They built grand facades to set the tone, or to distract you from the frustrating creep of progress bars. Some of them, it could be argued, got carried away. But we’re going to celebrate them here, in all their daft glory, just as soon as I’ve prepared the InstallShield Wizard.

Age of Empires

Like the game itself, Age of Empire’s installer strives to create a sense of industry, even as I pick a drive directory. There’s a topless villager lugging an enormous steak across the bottom of my screen. And at the top, a priest strides down a narrow tunnel, shepherd’s crook swinging back and forth. It’s as if a nascent civilisation was travelling through the wires of my machine, clearing space for a truly important game. Then a team of villagers walks to the centre of the screen and gets to work. The thud of their hammers recalls early soundcards, and beneath their crouched forms, the scaffolding of a new building begins to emerge. It grows in height and grandeur, and as the last file falls into place, reveals itself as a wonder of the world.

It’s not a humble metaphor. But given that Age of Empires is still standing, long after its original studio crumbled into dust, the prescience is striking.

Broken Sword

The VIP airport lounge of installers, lovingly preserved by the DOS Nostalgia channel. A classy voiceover lady talks me through a test of my display configuration and system speed. I’m half expecting her to offer me a complimentary coffee when the stone slats in the UI starts to slide across the screen, as if part of an ancient puzzle from the game itself. Broken Sword is fancy and it knows it.

Would sir care to play an arcade game while his adventure game is copying files? Sir would, very much. And so, once the disembodied English toff has confirmed I’m happy with the settings, the installer boots up a fully-functioning version of Breakout. I could get used to this. Must remember to tip the bellboy.

Worms United

A hand grenade sits on a desk, and next to it a camo laptop. Its black screen frames the reflection of a huge cartoon worm in a combat helmet - me, I suppose. As the disc spins, so do his pupils, in zany circles.

The masterstroke comes when the laptop flits to its own meta install screen. Rather than a progress bar, I’m faced with rows and rows of pixelated worms, each leaning on an explosive plunger. As the files copy, each worm detonates itself in turn, leaving behind an instant gravestone—just as they do in the game. It’s the perfect test: if I can’t handle this, there’s no way I’ll stomach Worms United’s pitch black sense of humour.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Diablo

Triggers a demonic laugh when you put the disc in, even in 2019, on Windows 10. Blizzard built its games to last.

Baldur’s Gate

There’s nothing exceptional about the software that installs Bioware’s first ever RPG, beyond the initial launcher that mimics the solid, granite aesthetic of Baldur’s Gate’s interface. What sticks in the mind is the physical act of folding out a case that contains no fewer than five discs. It’s like a comedy briefcase, and speaks to the scale of the adventure to come.

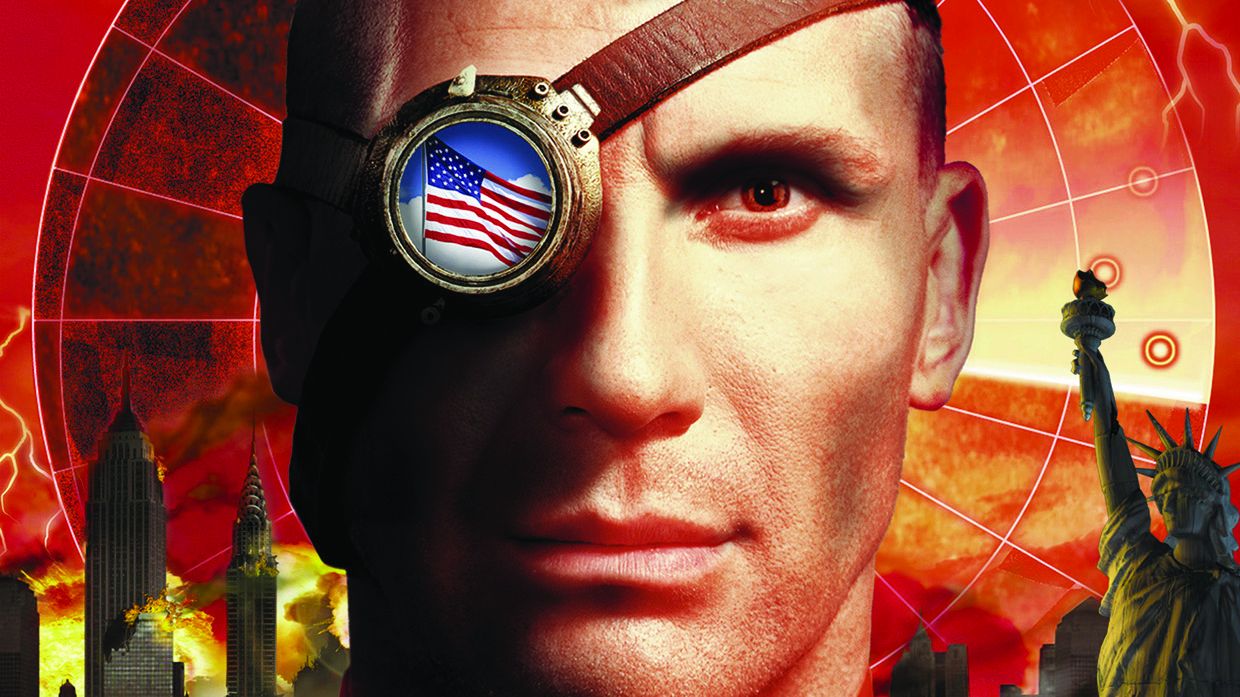

Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2

Seal extraction team has been scrambled to my location. As instructed, I’d made an oath of loyalty to the President of the United States, but my clearance code turned out to be incorrect. I have five minutes to enter my CD key, I’m told, or face “immediate liquidation”. And you thought Ubisoft was tough on piracy.

Westwood Studios often let its worldbuilding seep beyond the borders of its games. It turned the installation of Lands of Lore 2 into a CG flight through a wizard’s tower, and Command & Conquer into a conversation with a Tiberium universe AI. But the form peaked with the Red Alert series.

Seal team averted, I’m pushed straight into an emergency military intelligence briefing, where an American agent clicks through the slides to introduce the game’s backstory. I prefer the ending of the original Red Alert’s installation, though, which closes on the sound of marching feet and a quote from series villain Kane: “He who controls the past, commands the future. He who commands the future, conquers the past.” No one knows what it means, but it's provocative.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.