Accidentally stomping on humans as Jettomero, the galaxy's clumsiest hero

It's hard to do the right thing when you're a huge, clumsy death machine.

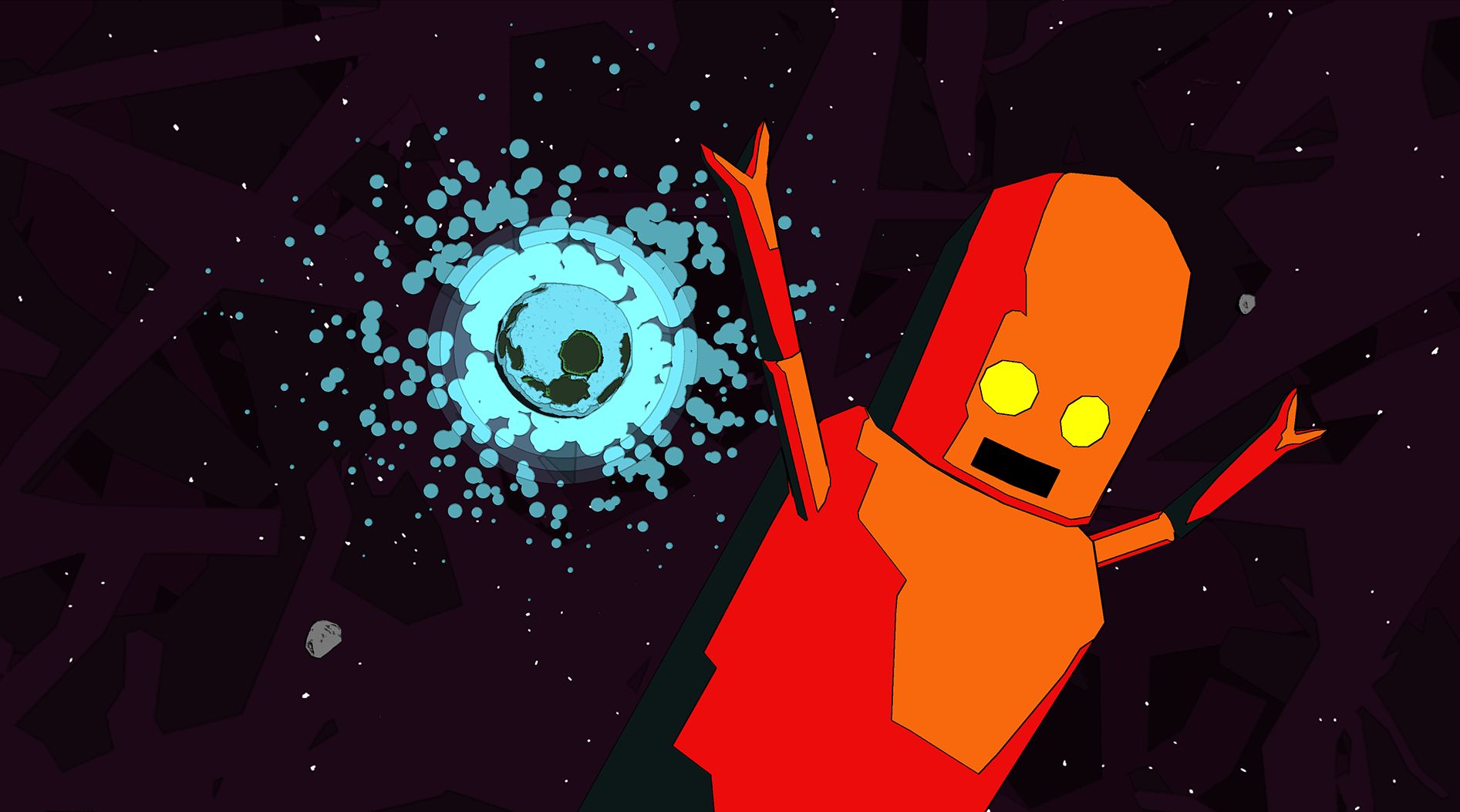

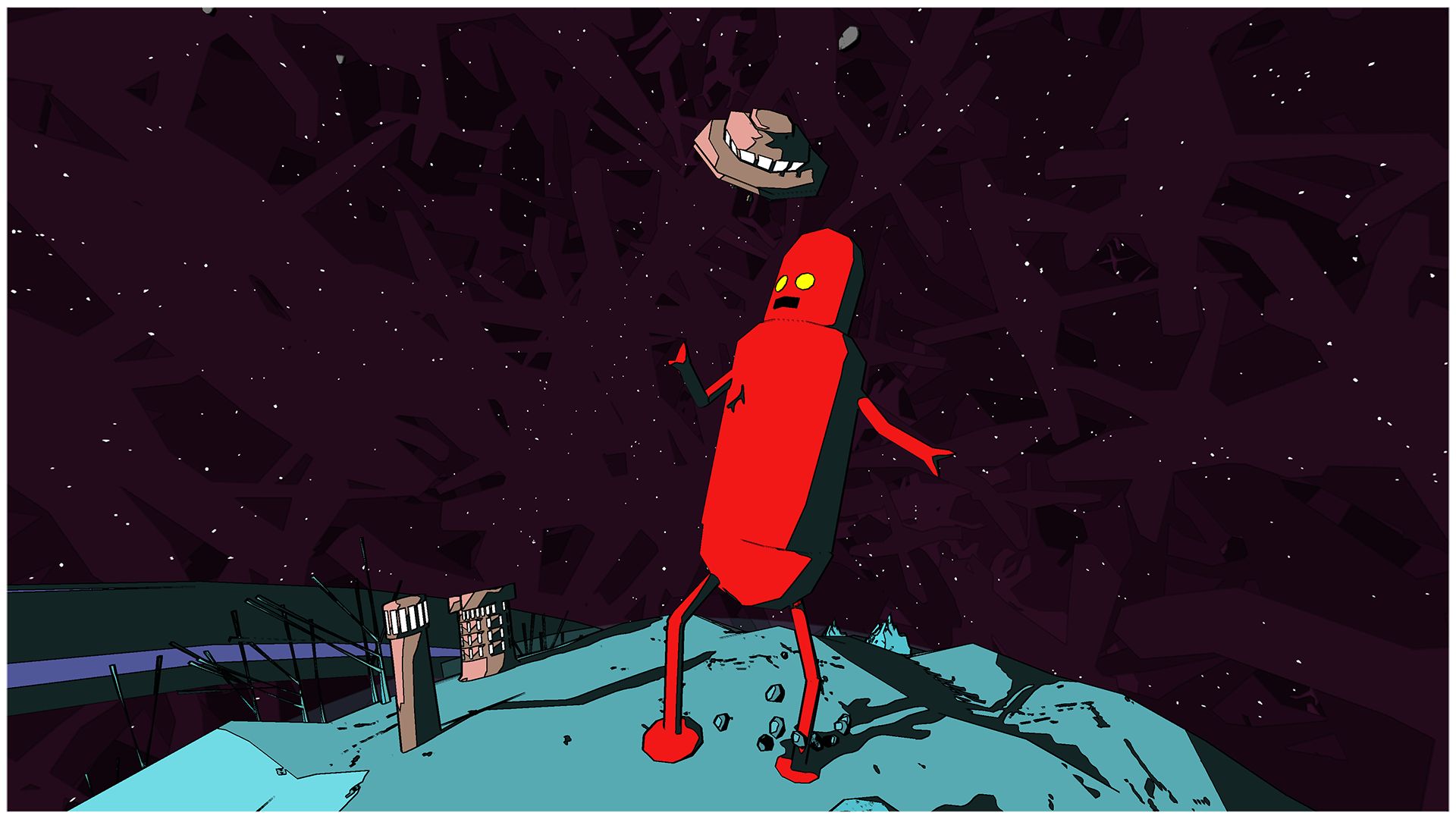

The last thing Jettomero wants to do is pose a danger to people. In fact, its sole objective is to valiantly protect an embattled human race—but there's a complication. Jettomero is a gigantic, lurching robot, a crimson tin-man cut loose in the cosmos who can circumnavigate entire planets with a few strides of its improbably spindly legs, razing human settlements to dust with a misplaced foot.

And Jettomero misplaces its feet a lot.

It's with more than a hint of irony that the hapless robot's in a game subtitled 'Hero of the Universe'. It's a title Jettomero aspires to, but is doomed to never achieve. Gabriel Koenig, the game's creator, began development with this concept: "a game that you can't ever win by doing what you intend to do."

Jettomero can't be a hero, because heroes don't unwittingly murder hundreds of innocent civilians. And Jettomero can't not murder hundreds of innocent civilians, because it's got all the coordination of a toddler taking its first steps. Koenig used procedural animation to create what he calls "naturally awkward" movement, providing the player with only limited control over each of Jettomero's planet-shuddering steps. Arms flailing, insisting that it means no harm, each plod of Jettomero is slow and painfully considered. But it's not enough to avoid catastrophe.

...some people will do everything they can to avoid the buildings, and other people will destroy everything that they can.

Gabriel Koenig

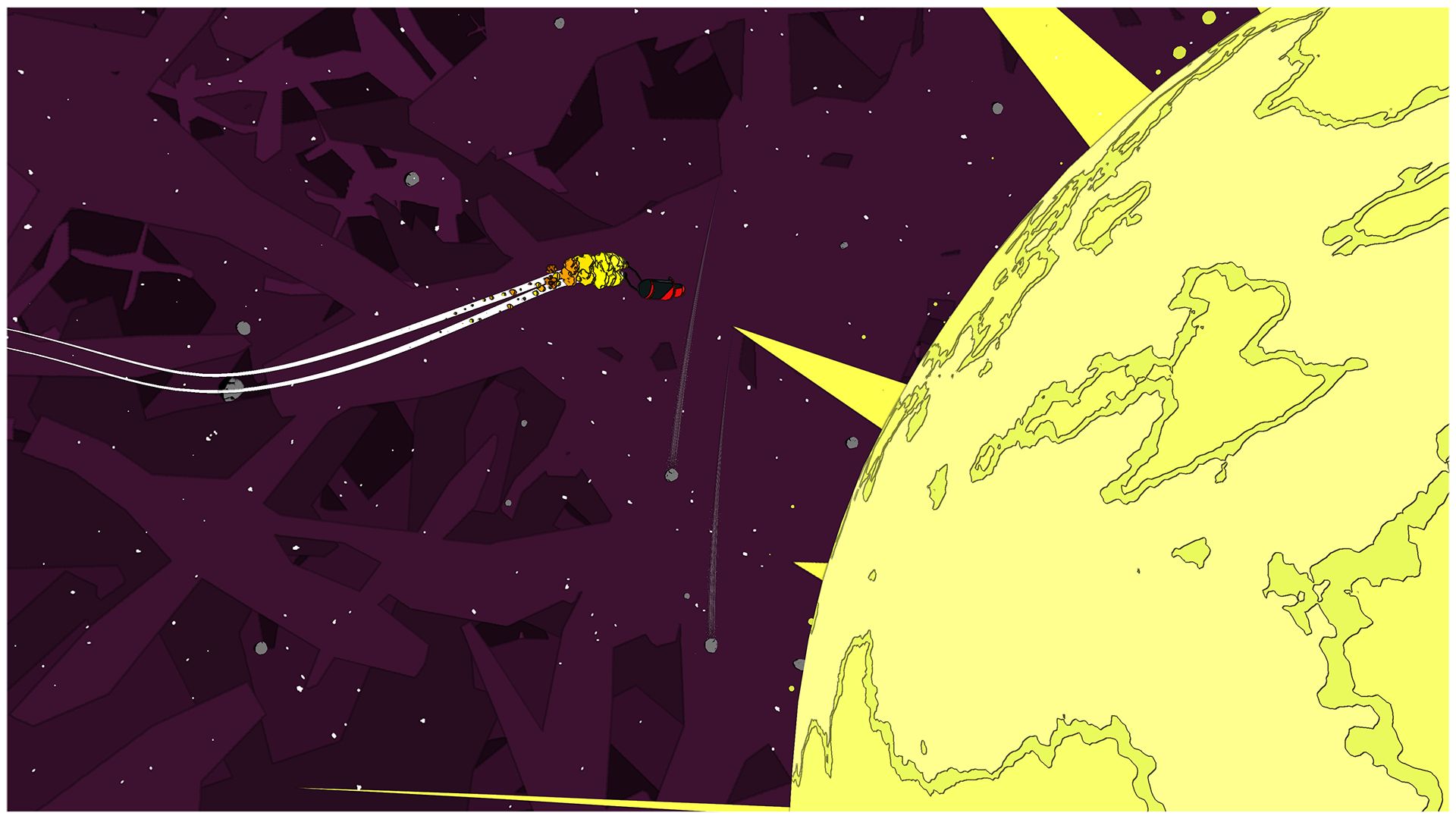

Seeing the trail of destruction left across the galaxy in Jettomero's wake, the inhabitants of the game's procedurally generated planets don't provide a hero's welcome. They swarm in their attack aircraft like gnats, peppering Jettomero with missiles and trying to pull the robot to ground using rope-like traps.

Being indestructible, Jettomero effortlessly shrugs off these attacks. There's little challenge to the game, which began as a Proteus-style exploratory experience. In the final game what it means is those who really suffer from the humans' antagonism towards Jettomero are the humans themselves.

Steering Jettomero through often densely populated planets is already a tough ask, but doing so while being besieged by the very people you're aiming to save is nigh-on impossible. Hostile ships clutter the screen, their missiles unbalancing Jettomero and making his movements even more erratic—his flustered stumbles even more damaging to the worlds underfoot.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It's rare for a videogame to grant the player such incredible destructive power and not have them revel in it, but the unerring positivity and sympathy shown towards humans by Jettomero, even while they attempt to destroy him, certainly suggested to me that wrecking stuff was to be avoided. Koenig's instinct is the same, and he found himself carefully treading around buildings even while testing, but he was also keen not to impose a correct way of playing.

"I liked leaving it open so that there weren't any punishments for that destruction," Koenig tells me. "In the videos I've seen of people playing it, it's kind of 50/50—some people will do everything they can to avoid the buildings, and other people will destroy everything that they can. It lets you tell your own story."

You can learn a lot about yourself based on how you play Jettomero. From my own approach (very careful to avoid destruction early on, becoming more ruthless after the story reveals humanity created Jettomero as a super-weapon, then mistreated and abandoned him) it turns out I balance generous instincts with a streak of Old Testament vengefulness.

Navigating these planets, the human inhabitants acting as both your chief irritants and your emotional impetus to continue, is when Jettomero is at its best. Facing off against kaiju-style monsters in defense of humankind lends Jettomero's quest a clearer focus, but the simple button-matching laser battles feel somewhat lacklustre.

Better is the game's way of relaying the various calamities that have led the humans to this position, a satisfying minigame which has you intercepting and decoding messages by rotating dials to switch letters, eventually revealing a forgotten slice of history.

But the weighty, ungainly feel of controlling Jettomero is a joy in itself, and this is what gives it life beyond its brief run-time. Merely being, to steal a wonderful turn of phrase from the game, a "vagrant of the cosmos" in this world is worth the asking price alone.

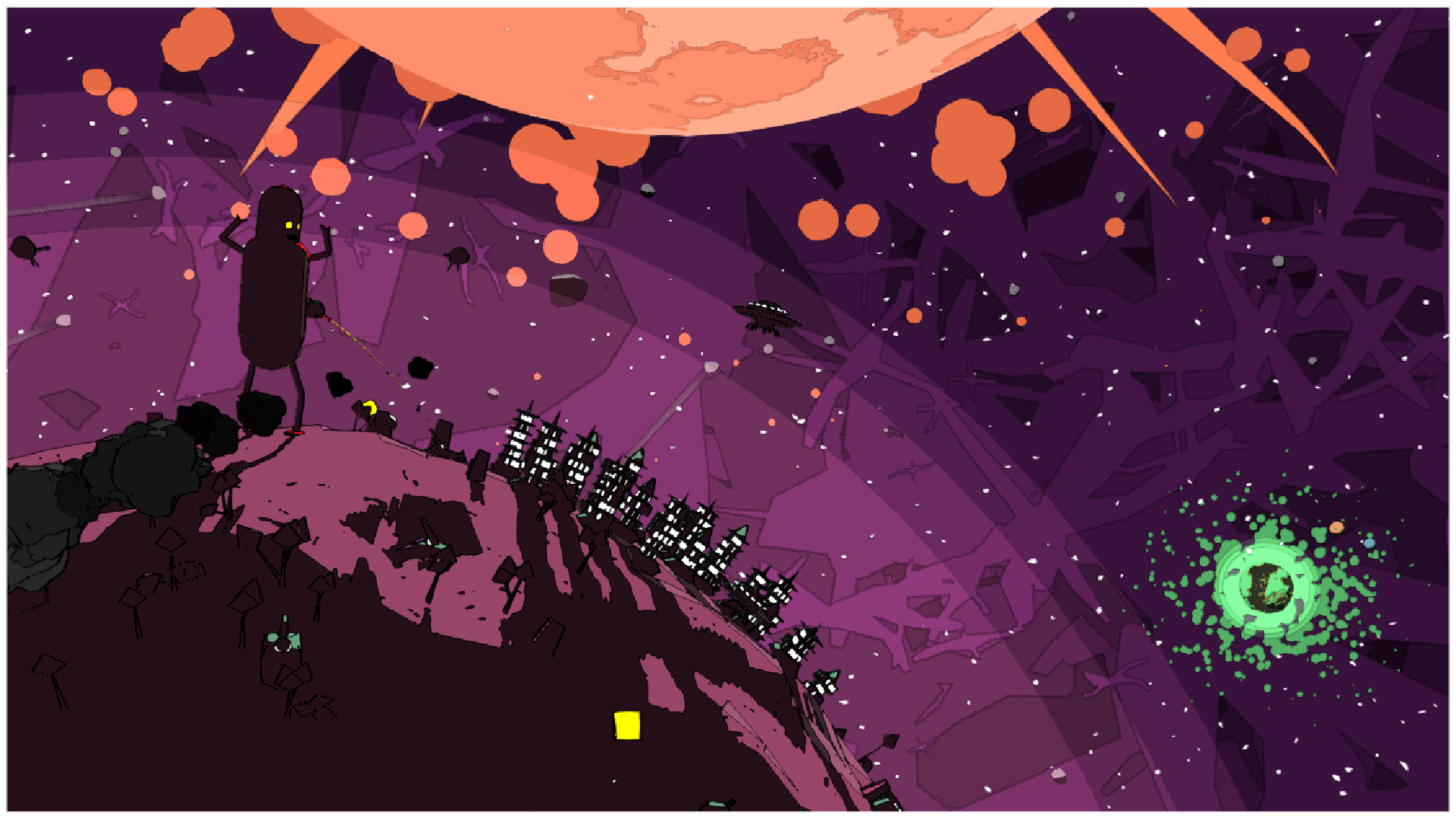

A large part of this is down the fact that it looks utterly fantastic. Koenig was heavily inspired by classic 1970s artwork when making Jettomero, and admits that it was a real struggle to convert that vibrancy to 3D. Whether or not he achieved that is up for debate but the result is utterly gorgeous in its own way.

It's a universe of bright colors and sharp contrasts, mint-green planets against deep purple skies, or whatever other combination procedural fate decides to throw up. It's hardly surprising that videogame photographers are already getting mileage out of the game's photo mode, but its very existence was merely a happy accident; Koenig initially introduced the in-game camera just to make the trailer, before realising that players might also enjoy playing with it.

It's the final piece of the puzzle, a serendipitous final addition that exemplifies the way in which Jettomero's many disparate elements and inspirations unite so harmoniously. Koenig's concept for this unwinnable game was initially 2D, but the keystone of its pathos was the move to 3D and the addition of procedural walking animation. Jettomero's relationship with humanity was already a complex and multifaceted one, then an injection of narrative made it so much more so. Sometimes, like a procedurally generated planet that could not have been designed better, these things just come together.