This article was originally published in issue 172 of Retro Gamer.

Despite renowned horror writer HP Lovecraft having authored some of the most haunting stories of the 20th century, for a long time his works remained noticeably unfulfilled in videogames, despite inspiration evident in games such as the Alone In The Dark series. By the late '90s, none had placed themselves within a recognisable world based directly on Lovecraft’s writings until Call off Cthulhu: Dark Corners Of The Earth, the story of private investigator Jack Walters.

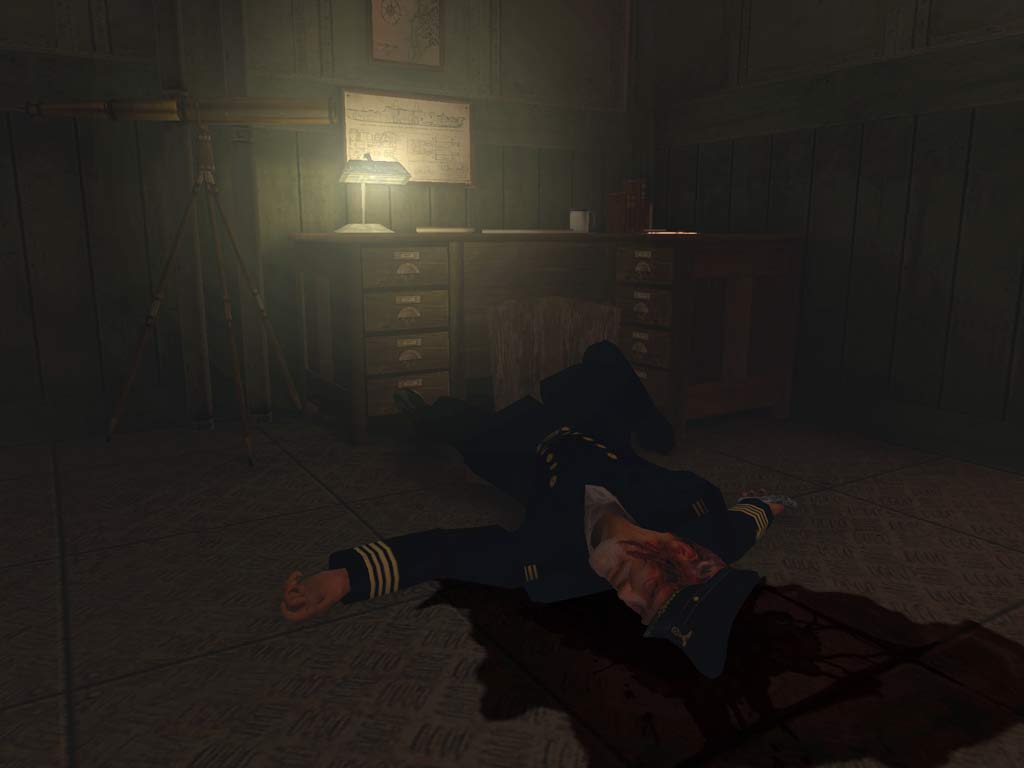

After a dramatic prelude in which Walters encounters arcane horrors that send him straight to the Arkham Asylum For The Insane, the detective apparently recovers, and finds himself once more behind his desk, investigating the disappearance of grocery store clerk Brian Burnham from the Massachusetts town of Innsmouth. Getting to Innsmouth is easy; getting out, and with your skin intact, is a different matter.

Dark Corners began life in that most '90s way, via the internet chat room. Within the group known as alt.horror.cthulhu, Andrew Brazier of Headfirst Productions, known primarily for Simon The Sorcerer 3D, posed the question: what would you want to see in a videogame of Call Of Cthulhu? The response from fans of the mythos was varied, but it would help shape the game into an accurate and fear-laden take on the famous horror writer.

"Back then it was the easiest way to get in touch with dedicated fans," recalls Andrew, "And I learned very quickly that mythos had a large and passionate following. I got a lot of good suggestions regarding what should or shouldn't be in the game, and even some suggesting the very idea of a Lovecraft videogame was sacrilege."

The challenge, Andrew continues, was to "make something that would interest Cthulhu fans, and also attract a new audience, plus ensuring the final game was actually fun to play". Headfirst’s director, Mike Woodroffe negotiated a licence with Chaosium, owner of the Call Of Cthulhu RPG, giving the development team an influx of resources and updated source material. Extracting themes from Lovecraft's own work was necessary but problematic. "He never used one word when 50 would do!" laughs Andrew. "So one of the main jobs as far as the story was concerned, was condensing key events down into something that would make an exciting narrative."

[The challenge] was to make something that would interest Cthulhu fans, and also attract a new audience.

Andrew Brazier

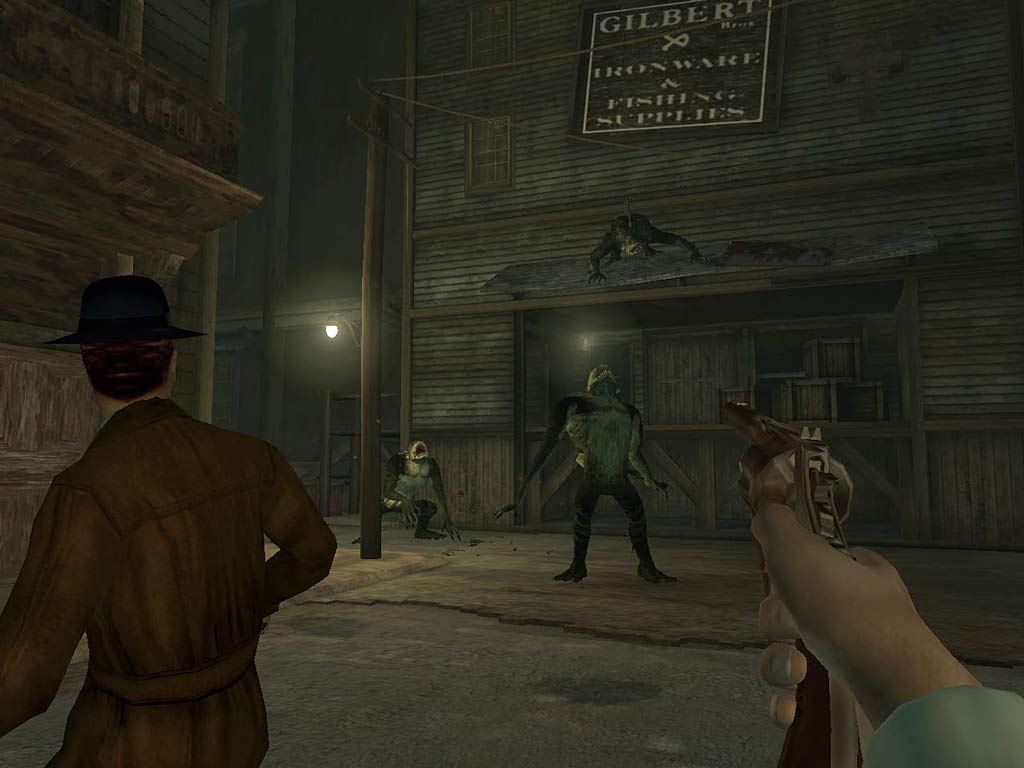

Lovecraft’s story, The Shadow Over Innsmouth, was the work that Dark Corners was to be most closely based on. "The main reasons were the cool spooky setting, and that it gave us a tangible enemy type in the hybrids [grotesque half men/fish breeds] and Deep Ones." As Andrew observes, many Lovecraft stories contain creatures beyond comprehension, making tense reading, but an unhelpful basis for visual interpretation, despite the author’s efforts at describing the 'indescribable'.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Innsmouth itself was an inspired choice for the majority of the game's setting; dark, foreboding, and full of hostile residents, the town’s background in mythos made it a perfect location. "The driving force behind the game was initially [Headfirst Creative Director] Simon Woodroffe," explains Andrew. "He set out the original design and plans for what we were trying to achieve. When development started, I was involved with design and technical art—there were a number of problems that needed solving, most notable how we were going to deal with lighting in order to create the atmosphere we wanted."

Also working at Headfirst was designer Chris Gray. "I'd played plenty of role-playing games, and knew that Lovecraft was a pioneering author," recalls Chris, "but hadn’t read the books. That said, I quickly became a fan, partly out of necessity, but mostly because the mythos is such a rich universe."

Buoyed by ideas from the chat group, the template was a HUD-less stealth shooter complete with a sanity system and story-based structure. "I remember brainstorming meetings where those key concepts were established," continues Chris, "and the focus put on story, rather than shooting. It just felt like a natural direction to take the game." Coming on board at this point was programmer Gareth Clarke, sold on the concept enough to choose Headfirst over other employment options. "It was such a unique game design that it became the game I wanted to work on," he reveals.

"It was a bit of a gamble because, apart from Simon The Sorcerer, there wasn’t a lot of people that had heard of them." The same year (2000), the game’s first publisher, Ravensburger, was secured and there followed a protracted period of negotiations as first it, then subsequent publisher Fishtank pulled out of the project.

"It was an absolute nightmare, as always when you're mid-development," recalls Gareth painfully. "We were pushed towards the concept of a 'vertical slice'—creating a full set of functionality for a limited portion of the game, the demo." Until this point, Headfirst had been developing Dark Corners using the Netimmerse engine and an early version of the Havoc physics engine. Then called Telekinesys, in-game physics were a relatively new concept at the time.

We proudly went to the nearest major videogame store the week of release and they didn’t have any copies.

Chris Gray

"They were doing some impressive stuff and needed a team to create demos to show off the technology," explains Andrew. Headfirst created a small section of a Cthulhu-themed game that demonstrated the fluid dynamics and ragdoll physics. A subsequent display at GDC in 2000 ensured the game received a lot of press, but there were drawbacks, as Gareth explains: "We were finding all sorts of issues with Havoc at the time—no negativity towards it, but it was in its infancy and we just couldn’t get it to do what we needed it to."

It was a similar story with the Netimmerse game engine. "It wasn't robust in terms of a game engine, unless you were running at 60 frames a second," says Gareth, and when publisher Bethesda signed the game in 2003, and shifted the focus from PC to Xbox, it was clear the two middlewares would not be suitable. "By today's standards, 60 frames would be fine but on the original Xbox and PCs of the time you were looking at 30."

With a new publisher on-board, but the extra challenge of its in-game engine and physics, development of Dark Corners began to slow with the increased workload on the small team. The first design and ideas had been scribbled down in 1999; now, in late 2003, Headfirst's exciting vision of the world of Lovecraft was as far away as ever. The team split into two as Simon Woodroffe focused on other projects, with Chris Gray assuming design and other responsibilities on Dark Corners. "It was my job to revise and edit the game to something shorter—the original plan had been 40 hours—and then add in all the detail and dialogue coordination with the rest of the design team."

The team spent swathes of time ensuring the player felt suitably unwelcome in the poisoned town of Innsmouth, its inhabitants pausing to stare at Jack or confronting him directly with a rough, gargled warning. The sound design was intrinsic, too, with certain effects containing a specific radius so they would fade ghostlike as the player approached, or random crying behind doors and cellar windows that would reveal disturbing scenes if spied through.

The collective PC Gamer editorial team worked together to write this article. PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.