Nvidia's next-gen GPU delays and cryptocurrency losses were crushingly inevitable

But it's what the green team does now that matters.

There's a sense of crushing inevitability to the recent Nvidia news. Not just the noises about delayed next-gen GPUs, or constantly changing leaked specs, but the drastic decrease to its gaming revenue. That and the fact it's now sitting on over $1 billion worth of last-gen graphics cards it could really do with shifting ahead of the launch of its new GPUs.

I mean, we kinda all knew it was going to happen; as the poster boy for matching moustache and eyebrow hair himself once said, history doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

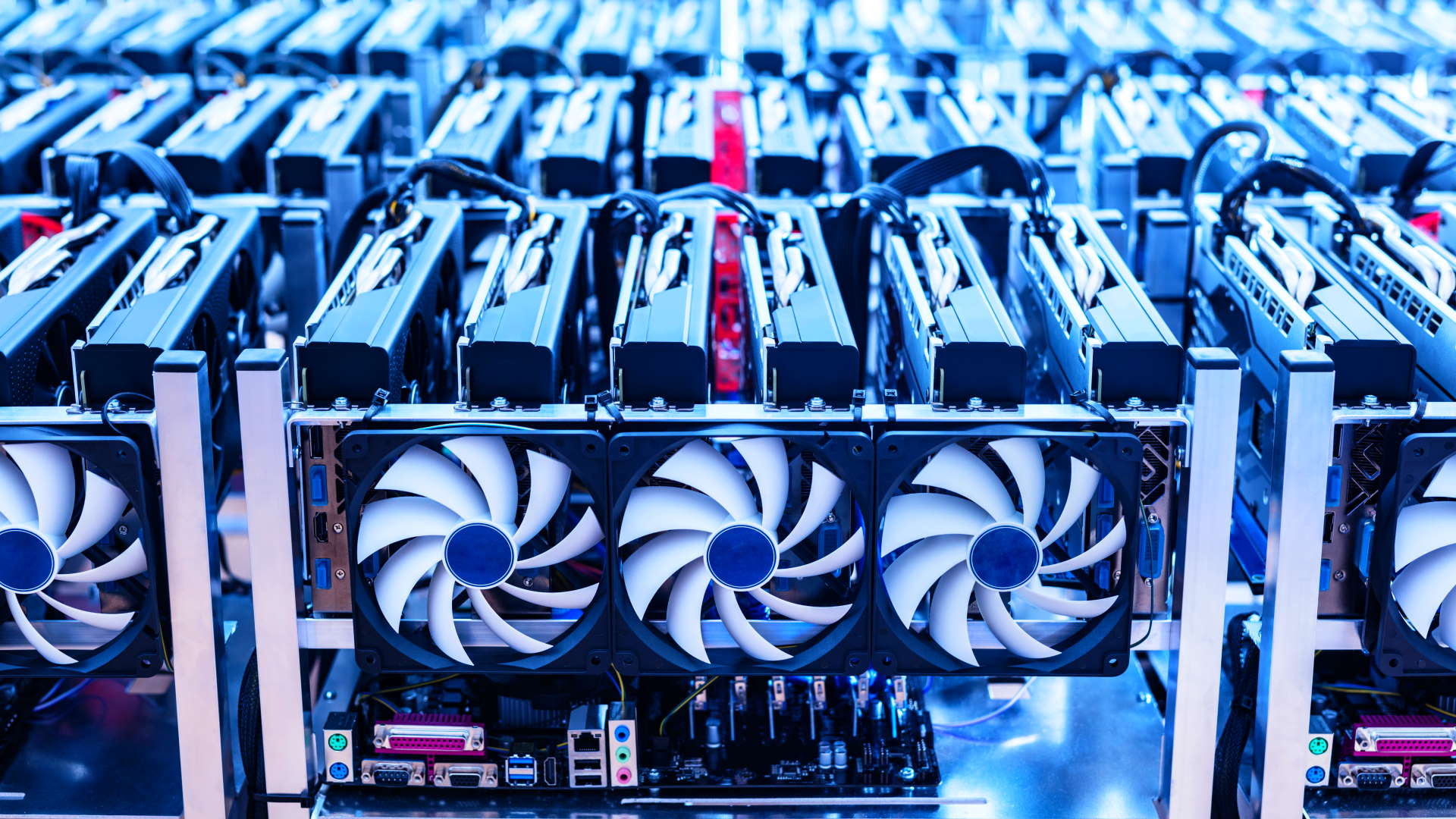

Cryptocurrency mining has made it all but impossible to buy a new graphics card over the past 12–18 months, with almost every new GPU coming off the production line going into mining rigs the world over. But the crypto bubble has now burst, with the yardstick value of bitcoin crashing and the ethereum network soon to move over the proof-of-stake model making those expensive GPU mining farms all but obsolete.

And so, after Nvidia pulled on all the levers it could to ensure a greater supply of graphics cards when demand was at an unprecedented level, now that's gone it's left holding some $1.32 billion worth of inventory that needs to be dealt with before it gets its next-gen GPUs out the door.

If we get more than one new RTX 40-series graphics card this year we can maybe count ourselves fortunate.

Which means the new GeForce series of graphics cards has seemingly been delayed, potentially with fewer new cards coming out this year, and the mainstream launches potentially put off indefinitely.

That's an intro that could have been ripped out of almost everything I wrote throughout 2018. But at least then we went into Gamescom and came out the other side with the RTX 2080 Ti, RTX 2080, and RTX 2070. Three separate Turing GPUs for gamers, at long last. If we get more than one new RTX 40-series graphics card this year we can maybe count ourselves fortunate.

And there will be much consternation about Nvidia delaying new gamer toys, and also concerns from investors and city folk about over $1 billion worth of missed revenue in the last quarter compared to targets. But it was inevitable, and honestly probably unavoidable.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Nvidia is blaming a huge drop in the gaming revenue for its missed targets, with this quarter's numbers dropping 44% compared to the previous quarter. But it's not really the fault of pesky gamers and their fickle desire for new GPUs, because all of Nvidia's crypto sales are wrapped up in the 'gaming' department, too.

Sure, the green team made some dedicated mining cards, but they barely scratched the surface of the crypto GPU bubble.

And now that the vast volumes of crypto card sales have dried up, the gaming revenue has shrunk. The volatility of cryptocurrency meant that another crash, akin to the 2018 one, was always likely, but as the main supplier of GPUs to the crypto mining market, Nvidia had no real option but to kick its supply into overdrive to support it.

Maybe there is some economics and supply chain genius out there with the perfect formulae for ensuring solid production during such a period of spiking demand without risking eventual oversaturation, but that ain't me, and I'm pretty sure they're not working at Nvidia either.

Dr. Thomas Goldsby called what the pandemic did to the supply chain a "Black Swan Event," something unprecedented that the production networks struggled to cope with. But crypto was different, something of a known phenomenon, but irresistible nonetheless.

The only chance Nvidia had to try and get cards through to gamers was to ramp up production, but it also had a responsibility to shareholders to capitalise on the huge financial opportunity that the latest mining boom afforded. A capitalist society demands this; choosing to keep production at a point where it could neither satisfy gamers nor miners wouldn't have served anyone and would have left investors frustrated to the point of questioning the leadership of the company.

But no one really knew when the bubble would burst, just that it in all likelihood would do. And with supply chain and chip production agreements necessarily covering long timescales, Nvidia couldn't just pull the plug as soon as the price of bitcoin fell off a cliff or when the eth org published the prospective date for switching to proof-of-stake. Indeed, Nvidia is reportedly still locked into significant GPU production contracts with Samsung for last-gen chips, which it had to honour.

What of AMD in all this? Sure, some of its RDNA 2 GPUs were used for mining, but Nvidia's Ampere cards had that mix of mining performance and increased availability, which made them far more sought after.

So, from my perspective, Nvidia has had no choice but to follow this path, knowing that in all probability it would lead to an eventual oversupply at the end of the current boom/bust cycle. But it's what the company does now that will be important, and this is what it can control.

Nvidia isn't operating in a vacuum, and some of its decisions will be made by the competition.

We've already heard rumours that it's now postponed the launch of its next-gen Lovelace GPUs, with the potential that it will only be kickstarting this new generation of GeForce graphics cards with a flagship RTX 4090 this year with the rest pushed to 2023.

Personally, I think it would be a mistake if it's hoping to clear RTX 30-series stock before getting around to launching the RTX 4080 and RTX 4070. If demand from actual gamers is low because a new generation is around the corner, delaying that generation isn't going to convince them to spend that money on an existing card if they've already made the decision to wait.

They'll just wait longer.

Maybe Nvidia is hedging its bets on the pre-built market, hoping to ship current-gen cards off to PC builders instead, all while holding back the next generation.

Nvidia isn't operating in a vacuum, however, and some of its decisions will be made by the competition. If AMD launches its RDNA 3 GPUs at a level that can top the RTX 30-series in terms of both price and performance, then that pulls the rug out from beneath the current-gen crop, making them a far tougher sell anyway.

Now the crypto bubble has burst there's going to be a hit no matter what it decides to do. But Nvidia now has to decide whether that hit is to be stretched out in order to clear existing cards before a delayed launch, or whether it can launch its high-end cards on schedule and readjust the pricing of its oversupplied stock accordingly.

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest

I think I've ably demonstrated I am no economics or business guru, but personally, I'd be inclined to stick to the next-gen plan, offer rebates out to the retailers and AIBs sitting on stock so as to adjust the price of the existing inventory, and just get things sold. Even if it's only launching the RTX 4090, RTX 4080, and RTX 4070 this year, stock of those new cards will be slight, and I'd wager with adjusted pricing it could still sell through a huge chunk of the outstanding last-gen GPUs.

Either way, the money would still be coming in.

But I'm sure there are sensible arguments against that, and the most likely course of action right now would see a solitary high-end RTX 4090 launch in October, with potentially an RTX 4080 just before the end of the year at the outside. And then Jen-Hsun crossing his fingers that people will still suck up RTX 30-series cards priced like there's no next-gen on the horizon.

Dave has been gaming since the days of Zaxxon and Lady Bug on the Colecovision, and code books for the Commodore Vic 20 (Death Race 2000!). He built his first gaming PC at the tender age of 16, and finally finished bug-fixing the Cyrix-based system around a year later. When he dropped it out of the window. He first started writing for Official PlayStation Magazine and Xbox World many decades ago, then moved onto PC Format full-time, then PC Gamer, TechRadar, and T3 among others. Now he's back, writing about the nightmarish graphics card market, CPUs with more cores than sense, gaming laptops hotter than the sun, and SSDs more capacious than a Cybertruck.