Meet the most honest man in EVE Online

How to become the most trusted person in a game where the first rule is to never trust anyone.

When you're the most trusted person in EVE Online, your reputation has a way of preceding you. For years, the name 'Chribba' felt like an urban legend to me—a man you can trust in a galaxy where the first rule is to trust no one. Inside the Harpa convention center in downtown Reykjavik, I meet Chribba amid the bustle of players gathering for EVE Online's annual Fanfest. Like the thousands of other EVE fans, Chribba has made the pilgrimage to Iceland to meet friends and spend a weekend talking about CCP Games' sandbox MMO. But for him, perhaps the closest thing EVE Online has to a celebrity, a public gathering like Fanfest is a unique experience.

If Chribba is EVE's most honest player, then Scooter McCabe is its most dishonest. A scammer with a silver tongue, Scooter has stolen everything from spaceships to entire regions of space. Find out what it takes to become a scammer in EVE and then read about the moment where Scooter went from playing villain to hero by rescuing a group of noobies from the clutches of a slave camp.

"It's kind of weird because I don't like being the center of attention which puts me in an awkward position when I come to somewhere like this," he explains. "There's a lot of people that I've never met that want to say hello, shake my hand, and get my photo. That's so surreal to me."

Chribba stands alone in the bizarre sphere of the EVE social elite. He's not an alliance leader known for conquest, an industrial savant, or an infamous scammer. His entire reputation is built around the idea that, unlike so many people in EVE Online, he will never screw you over. Chribba is EVE Online's first trade broker—the only person you can trust to make sure that when billions of ISK is changing hands in EVE's most lucrative deals, no one is getting ripped off.

Star destroyers

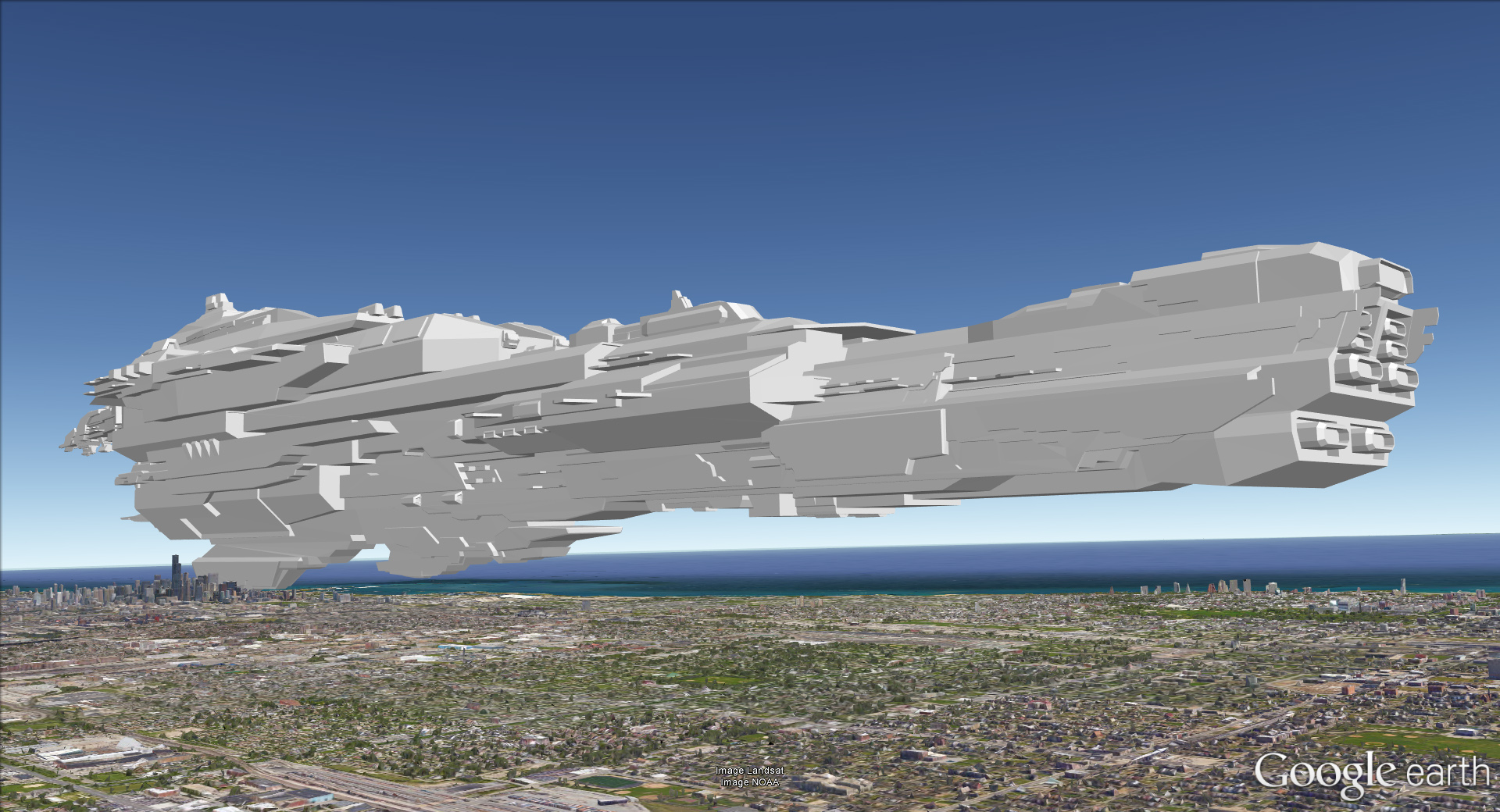

The first time you see a titan is a special experience for any EVE pilot. These 14 kilometer-long supercapital-class ships are the nuclear deterrent of EVE's biggest alliances. When two enemy fleets engage in battle and one decides to deploy supercapitals, an ever-escalating arms race erupts where the only response from the other fleet is to see the bet and raise. This back and forth of committing more supercapitals to overpower an enemy is the catalyst for nearly ever bloodbath in EVE's history.

But titans are a massive investment in more ways than one. Not only do they cost around 100 billion ISK, making them the most expensive ships in EVE, they also take weeks to build and half a year just to train the requisite skills to pilot. Once you take your seat in the captain's chair, a whole new world of responsibility bears down on you.

Titans and supercarriers (the other type of supercapital ship, though considerably cheaper) are extremely vulnerable on their own. They either need to be moved with a supporting fleet or with total discretion, unless enemy spies spot you and raise the alarm. Many supercapital pilots play multiple characters simultaneously, acting as their own scouts to make sure the coast is clear when moving. Titans are such a massive liability but so necessary to the backbone of any military that players jokingly call them 'space coffins' because some pilots feel buried by the responsibility. Needless to say, titans are ships reserved for EVE's most hardcore pilots. And yet, for all the hassle that goes along with owning one, getting rid of one is even worse.

Titans are such a massive liability but so necessary to the backbone of any military that players jokingly call them 'space coffins' because some pilots feel buried by the responsibility.

As we find a quiet place to talk, Chribba tells me that when titans and supercarriers were first introduced in 2005, trading them was a nightmare. Most items in EVE Online can be sold through its automated marketplace, providing a safe way to exchange goods including most ships—except supercapitals. These behemoths were, at the time, too big to even dock inside of EVE's largest space stations. If pilots wanted to trade one, they'd have to do the exchange in open space where a million things could go wrong. It also led to the age-old conundrum of drug dealers: who hands over the goods first?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"I had a friend of mine that was buying one and wasn't sure about the party selling it, so he asked me if I would help out," Chribba explains. He'd been playing for a few years and had built a small reputation among the community thanks to several EVE-related websites he created.

The deal was simple: Acting as a neutral third-party, Chribba would hold the money until his friend was sitting comfortably in the cockpit of his new weapon of mass destruction. Once his friend had made it to safety, Chribba would then transfer the money to the seller and everyone would walk away happy. In that moment, Chribba could've done what a healthy portion of EVE's players would do. He could have run. But, as he tells me, that's just not who he is.

After the deal concluded, Chribba's reputation as a trustworthy broker began to spread. Eventually, he tells me, that led to him to taking his business public as Chribba's Third-Party Service. "It just skyrocketed," he says, a proud smile creeping across his face. "The more trades I did the more trusted I became, and it just grew more and more."

It didn't matter who you were or who you flew with, if you were buying or selling a supercapital, Chribba would be there to make sure the deal went down smoothly. As supercapital ships became more common, Chribba's business became one of the most profitable in EVE Online. Trillions of ISK passed through his hands. With each deal earning him a 300-500 million ISK cut, billions of that ISK was dropping into his bank account.

Based purely on his word, Chribba had eliminated the stress of EVE's riskiest transaction. Where trading titans used to feel like a drug deal in the New Mexico desert, it was now as cordial as buying a car. But just because Chribba has a reputation for being honest doesn't mean that his clients do.

Bad deal

Deep in the lawless reaches of null-sec space, Chribba watched as the egg-like life pod ejected from the supercarrier. In his wallet was just over 20 billion ISK—the going rate for supercarriers. As the seller's pod drifted away from the four kilometer ship, the buyer began thrusting towards it, eager to step inside the ship that would become his crowning achievement as an EVE player.

Agonizing seconds passed before the buyer's pod came within docking range of the vacant supercapital. He right-clicked on the hull, selected the board command, and waited for his camera to update to the perspective of his shiny new weapon. Unable to let his guard down until his purchase was behind the shields of a friendly starbase, the buyer fired up the jump drive to initiate the warp to the safety a nearby star system.

It was only when the warning text appeared that he realized something was wrong. The seller had fully drained the supercarrier's capacitor, leaving it a sitting duck for minutes until it charged up enough that the buyer could warp away. But Chribba didn't know this. Instead, all he saw was the buyer enter the ship and then, almost immediately, disconnect from the game. Whether this was an untimely connection issue or a split-second panic decision to quit, Chribba will never know.

That was me being a little naive, I think. In my mind I was like, why would anyone want to try something against me?

Tension boiled over as Chribba tried to figure out what had happened. "I was confused," he says. "Why did he just disconnect? Is he done? Is he leaving?" The seller began messaging him, growing more and more insistent that Chribba hand over the money immediately. "This could be a bad thing," he recalls of that moment. "I remember being nervous about what was going to happen, and I was just hoping they'd be nice guys. It was confusing and I was very nervous." Not knowing what else do to, and since the pilot had vanished in his supercarrier, Chribba transferred the 20 billion ISK.

Just then, the buyer logged back in and rematerialized.

"When it happened I was just like, 'oh no…'"

On Chribba's overview window, four new ship signatures immediately appeared as four ships exited warp tunnels, landing right on top of the supercarrier. Within seconds, the gang triggered their anti-warp modules and disabled the buyer's new supercarrier. It wasn't going anywhere—at least not for ten or so minutes until its jump drives had the required amount of capacitor to fire. Chribba watched helplessly as one of his clients ransomed the other.

I ask Chribba why the buyer didn't just stall the scammers until the capacitor had recharged. With only four ships, the pirates would've needed to call in bigger muscle to make good on their threat and that could've taken a lot more time. "This being a new era of capital ships, you didn't want to risk losing it," he says. "It was such a huge deal to have access or even buy one of these things."

To illustrate this, he tells me that some players were so nervous about buying a supercapital that they often had trouble clicking the board option in the drop-down menu because they were shaking too badly. While it's just a game, the months of effort and saving that go into buying one are, in that moment, all too real.

Looking back, Chribba has to laugh. "That was me being a little naive, I think. In my mind I was like, why would anyone want to try something against me?"

I ask him if he remembers who the scammers were. When he tells me, it's my turn to laugh. "The sellers were Guiding Hand Social Club"—or, as most non-EVE players would recognize them, the most infamous group of scammers who once orchestrated a ten-month plot to eradicate an entire corporation just to settle a personal vendetta. In hindsight, Chribba knows he should've seen it coming.

"I'm there to help people and do my job, and it was one of those times where I couldn't deliver—obviously that feels bad. But it feels much worse later on after doing 4000 trades instead of four." Simply put, he just didn't know better.

No space for old men

Before meeting Chribba, I had a few conversations with random players I bumped into while wandering the lobby of the Harpa convention center. In a game where opinions on specific people vary wildly depending on who you talk to (and what grudges they have) Chribba is an immutable constant. If I were to believe what one player told me, he's the virtual incarnation of the Dalai Lama.

That reputation isn't just cemented through being a trade broker, but Chribba's immense passion for EVE's community. Over the years, he's programmed half a dozen EVE-related websites like EVE-Search, which mirrors and archives EVE Online's forums while providing access to powerful search tools so that a massive portion of its culture is never lost. Then there's in-game community events like Lovecans, where Chribba deposited large sums of ISK into cargo canisters and ejected them into space for other pilots to find.

To have earned the love and respect of a community with a reputation for brutal skullduggery is Chribba's greatest accomplishment. It's why I can't help but feel a twinge of sadness when he admits he doesn't play that much anymore. "I was involuntarily retired, in a sense," he shrugs. "The need for brokering is way, way less than it was."

In 2016, CCP Games released the Citadel expansion which rolled out new kinds of player-owned space stations that dramatically changed many aspects of EVE Online. But while Citadel is a popular addition to the game, it had one casualty: "It killed the supercapital brokering market overnight," Chribba explains.

The largest citadels, veritable Death Stars in their own right—if you can forgive the Star Wars analogy—are big enough that supercapitals can dock inside of them. Players can now transfer them without all the tension or risk of doing it in open space, and after over a decade of business, Chribba's Third-Party Service is obsolete.

When I ask Chribba how that feels, he shrugs. "It's good and bad. I loved to be in that position, it was nice to be admired, but at the same time it put a lot of pressure and stress on me. I saw a need for something that wasn't provided for, so my goal was always to provide something until it wasn't needed or something better comes along. With brokering, there wasn't a feature or function for this, but now there is."

I don't want to be the bad person, even if I can be. I know it's a game and I could be an asshole and get away with it, but even in real life that doesn't really appeal to me.

Chribba doesn't seem sad. Rather, brokering was just another way he could give to others. In return, he gets to be a beloved member of a community. "I'm really not anyone special, but people seem to think so, and that's really helped me to grow as a person. Even if I don't think I'm anything, they appreciate me and want to say hello. It's super humbling to see that I'm affecting people in a good way where they want to say hello. If it weren't for the community, I wouldn't be playing."

Like Chribba, EVE Online's reputation precedes it. People love to condemn EVE players as assholes, trolls, and scum—and for many players it's an apt description. But according to Chribba, that's the joke. "It's something that became very clear after my first Fanfest," he explains. "You have all these enemies in-game, but they're at a party and they're buying each other drinks and they're friends."

And yet, despite that freedom to be an ass in-game, Chribba still doesn't give in. "I don't want to be the bad person, even if I can be. I know it's a game and I could be an asshole and get away with it, but even in real life that doesn't really appeal to me. You have to treat others the way you want to be treated, and that's followed me into the game."

I don't know why a man I just met spouting a platitude I learned as a kid feels profound. But it does.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.