How game devs avoid Twitter drama, according to Daybreak

The reputation of Daybreak Game Company, the studio formerly known as Sony Online Entertainment, took a hit in February when it laid off employees shortly after changing ownership. Something that we hope Daybreak will continue to have a good reputation for, though, is its transparent approach to development. Its president, John Smedley, is one of the more outspoken, honest, and engaged company heads in the industry. The same could be said of its current and former leads: Matt Higby of PlanetSide 2, David Georgeson of EverQuest Next, and the H1Z1 dev team have all had a big presence on Reddit, Twitter, or on in-house livestreams.

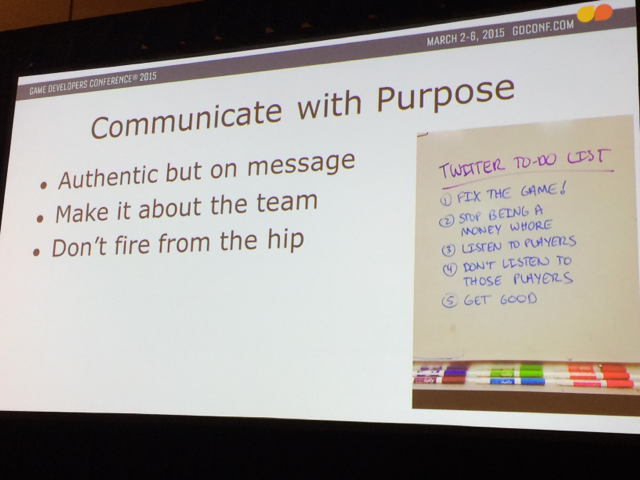

How does a studio with multiple living games empower its developers to be vocal without over-promising or adding fuel to flame wars? Daybreak's Tony Jones, senior community relations manager, shed light on Daybreak's approach to social media during his panel at GDC this week, "Balancing Community Management With Transparent Development."

In the talk, Jones emphasized a few key policy points. "Training is crucial for development teams. Putting your teams on Twitter with no training, you might as well just hand them a loaded gun. The ability to say whatever we want when we want to say it is extraordinarily dangerous." Jones also said that it isn't the community manager's job to police developers' tweets, but to be constantly listening and provide insight and advice. "It's not that you try to restrict what they're saying, it's that you try and slow them down and think about what they're saying before they say it. Everyone's tone should be the same. Don't have 'grumpy cat' on one side and, you know, super hyper guy on the other side. You want to kind of make that middle ground and make them appear as a cohesive team. Show them the common pitfalls. Show them what trolling looks like. Show them what kind of things... maybe you don't want to tweet a lot about Gamergate, maybe you can tweet a statement and just kind of walk away from it. Things that get them into trouble later on, things that may cause them additional grief. Maybe they want to tweet about Gamergate, just tell them what's going to happen in advance."

During the Q&A section of the talk, Jones gave an anecdote when asked how he'd respond to a developer who's saying too much—or the wrong thing—on Twitter. "When you're working with a developer who says things that you're not particularly wanting them to say, there's a couple different things they should know. First of all, if it's already out there, it's already out there. I had an associate programmer who got really engaged with at Gamergate. It started out as a 'Hey, you may want to be careful with this' and it got to be a 'Hey, dial it back a bit.' You can put a disclaimer in your 'about' section all day, but [players] still know that you're an associate programmer on this game. Part of it's training, part of it is just building up a relationship and asking them. They're making your job harder. I'm not saying go to them and beg and cry, I'm not saying that's worked—but it has. Making them aware of the potential impact of what they do I think is crucial."

To Jones, it's also important that multiple developers aren't competing with one another or contradicting on social media. "Your Twitter followers are not a Gamerscore. It is all about your team. Everyone should be working together, not jockeying for position on Twitter or on Reddit. Everyone works together, succeeds and fails together as a team, that includes the community management team."

One of the big challenges that many studios are facing, according to Jones, is how much information to give players. "There's plenty of risks and rewards to it."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Arma 2. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging. Evan also leads production of the PC Gaming Show, the annual E3 showcase event dedicated to PC gaming.