Weird Weekend is our regular Saturday column where we celebrate PC gaming oddities: peculiar games, strange bits of trivia, forgotten history. Pop back every weekend to find out what Jeremy, Josh and Rick have become obsessed with this time, whether it's the canon height of Thief's Garrett or that time someone in the Vatican pirated Football Manager.

Dwarf Fortress has achieved mythical status for its furiously detailed algorithmic worlds, its legendarily long development, and the fact that its creators, Tarn and Zach Adams, seem content to continue working on it for the rest of their lives. But Bay12 Games' monument to emergent storytelling isn't the only project of its kind. In fact, it isn't even the oldest life simulation that's still in active development.

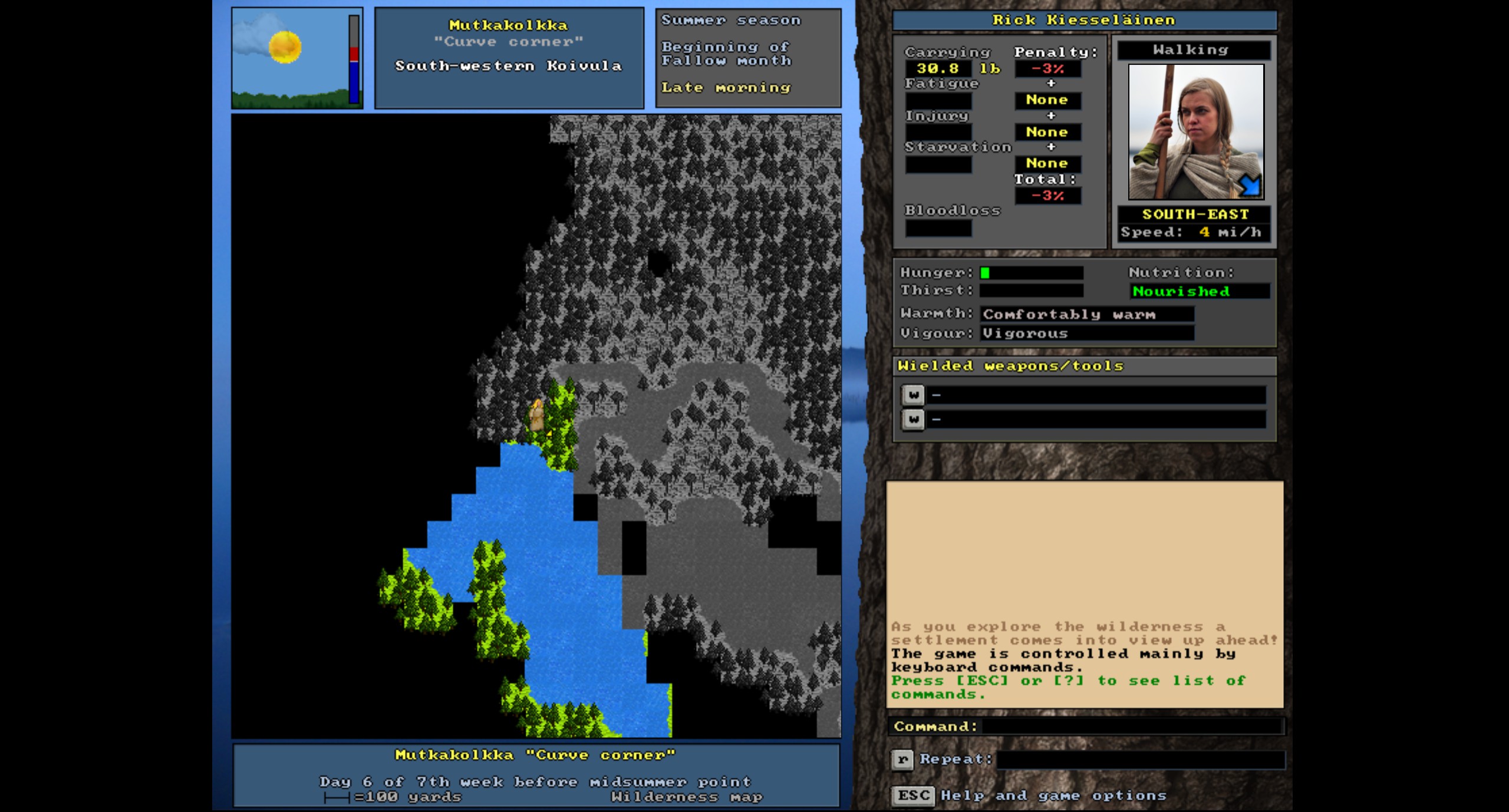

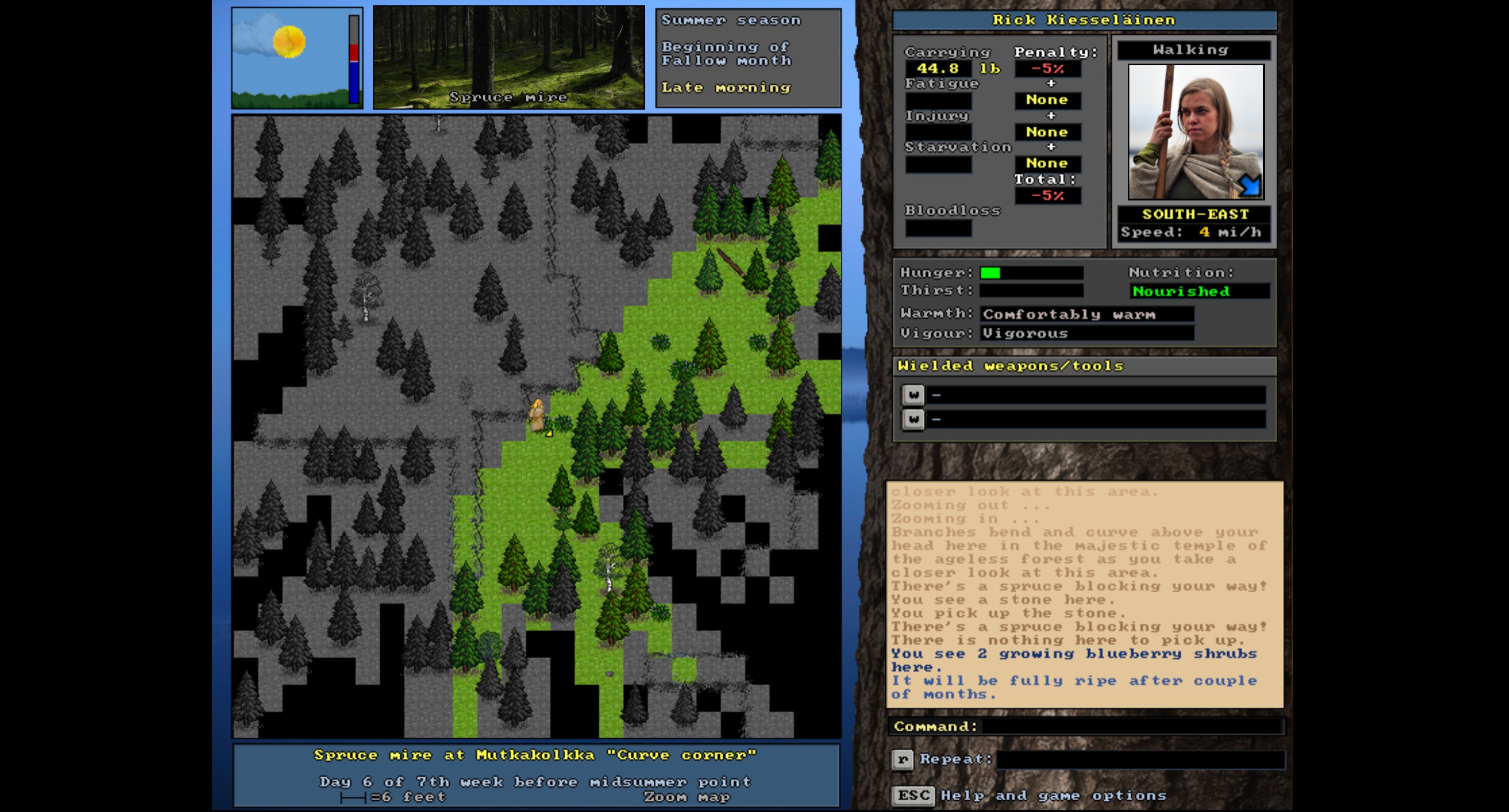

Indeed, while calling UnReal World the Dwarf Fortress of survival gaming is convenient shorthand, it might be fairer to say that Dwarf Fortress is the UnReal World of fantasy fortification management. A procedurally generated survivalist roguelike set in Iron Age Finland, UnReal World has been in continual development since 1992.

In the decades since it launched, UnReal World has amassed a dizzying array of systems. It pioneered mechanics like crafting and shelter construction years before they became mainstream, while it also boasts complex animal AI, a highly detailed combat system that simulates injuries to specific body parts, and magic inspired by Finnish folklore. And it's all the work of just two people.

UnReal World is the creation of Sami Maaranen, who together with programmer and longtime UnReal World collaborator Erkka Lehmus, runs the indie studio Enormous Elk. Maaranen began designing UnReal World when he was just 14 years old, having learned to code during his childhood.

"At about the age of maybe eight or nine, we got our own Commodore as a Christmas present, but it wasn't a Commodore 64, it was a Commodore 16, because it was a little bit cheaper," Maaranen tells me over a scratchy video call from his home in rural Finland. "We had my uncle visiting [that] Christmas, and he was a bit of a tech guy, into computers and stuff, and he used to read this manual to us kids, me and my older brother."

Eventually Maaranen graduated to a PC, where he became obsessed with online Bulletin Board Systems, even running his own for a time. "The BBSs were full of interesting indie games, and I found the roguelike [genre]—Nethack, Moria, Omega—and they hit me really hard," he says. "At some point I thought 'Hey, I'll try to create a roguelike of my own.'"

This initial version of UnReal World was a more traditional fantasy roguelike than the one playable on Steam today (it also just launched on GOG). "It started as mimicking or borrowing ideas from the games that I liked," he says. Maaranen was further inspired by pen & paper roleplaying games like D&D and RuneQuest. "I was a big fan of those fantasy worlds."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Maaranen sold the first version of UnReal World through the BBS boards using a shareware model, with the goal of making enough money to avoid having to get a summer job. "That was the usual chore you had to do as a schoolkid," he says. "I thought maybe enough people would buy it so that I don't have to get the summer job and continue on the programming, and it worked out."

As Maaranen entered adulthood, his interest shifted toward more grounded roleplaying settings, first through more "realistic" pen & paper RPGs like Hârnmaster, then eventually the real world itself. Specifically, Maaranen and Lehmus developed a fascination with ancient Finnish history and mythology, which Maaranen puts down to them growing up as countryside kids. "It seemed like many roleplaying games had this generic medieval fantasy world," he says. "There was a feeling that, if we are going to continue making UnReal World, it has to be something different."

Consequently, Maaranen began nudging UnReal World toward its current historical setting, replacing the high-fantasy races with Iron Age human cultures. The first survival elements arrived sometime in 1996, such as a weather system, simulated hunger, and the ability to build shelters. "For a long time, it wasn't the purpose to create a survival game," Maaranen says. "These elements came naturally because we tried to recreate the worldview and traditional mechanics of livelihood for ancient people, and it's a lot about survival."

While there are obvious platform milestones for UnReal World, such as its debut on Windows in 1999 and its arrival on Steam in 2016, it's harder for Maaranen to single out key moments in its design history, simply because its updates have been largely iterative and relatively consistent. That said, he does recall a few important moments, such as the addition of a crafting system, which arrived around 2005.

"It came from one of my friends who was playing the game a lot at the time. I remember quite clearly the first time he suggested that 'Hey, Sami, wouldn't it be great if the player character could craft something?'" Maaranen explains. "And at first I thought 'Nah, I don't think it's necessary.'" Yet Maaranen reconsidered, eventually adding a basic system to craft simple weapons—"probably something like a primitive javelin or club".

The players went wild for it. "They loved it and they wanted more," Maaranen says. As such, crafting has become a major part of UnReal World, with many recipes and crafting methods based on historically authentic processes that Maaranen has tried out for himself. "Like how to make thread out of a nettle plant," he offers as an example. "[It] contributes to the game, because I want to transfer as realistic [an] experience as possible."

Another element Maaranen is particularly proud of is UnReal World's magic system, which is based heavily in ancient Finnish folklore. "The spells and rituals and magic that exist in the game, they are picked up from real spellbooks that have been preserved by recording old people's tales," he says. "It has been really interesting to go through those and pick the ones that fit the game."

Today, UnReal World is a completely different game from the one Maaranen originally made. He estimates that only 5% of the underlying code remains the same as it did in the early 2000s. "[There are] some ancient functions somewhere, or ancient remarks," he says. "Sometimes when I go through the code, fixing or adding something, I come to think 'what's this?'"

For Maaranen, UnReal World is more than just a project, it's a companion that has been with him for most of his life. The amount of time he spends on it ebbs and flows with his lifestyle. There are periods when he works on it full time, or periods when it's more of a part-time concern. But it is always there, always the project he is drawn to creatively. Indeed, while he's dabbled with making other games in the past, he always ends up coming back to UnReal World.

"In a big simulation game, when it's set in history and when you are basically doing everything by yourself as an indie coder, if you have any ideas—good game ideas, good feature ideas—you can put them in there," he says. "If you want to create a fishing simulator, you can create it within UnReal World, you can spend a year polishing the fishing mechanics. If you want to create a story-based game, you can add a really nice quest to UnReal World."

To date, Maaranen has been working on UnReal World for 33 years, and there are countless features he still wants to add. His current development focus is clothmaking, which he plans to make "much more detailed and more hardcore". After that, somewhat appropriately, he wants to add permanent NPC companions who will accompany the player through their life, including the ability to get married. "It's quite a big change, actually…because now it's a single-character world," he points out. "It changes the game quite a lot, if somebody will stay with you."

There are also some dream features Maaranen would like to add, if he can find the time or resources to do so. "If I had all the time and also power in my hands, I would like to make the other human beings in the game world [have] a lot more artificial intelligence," he explains. "You could have greater interactions with them, and they would be more aware of things, so they would become more alive."

Such features could be years in the making. But it's entirely possible that Maaranen will achieve them, as he has no intention to stop working on UnReal World, ever. "It's quite impossible to see that happen, because when I accomplish one feature, I always have two more waiting," he says. "So, in that sense, it can't be finished. When my imagination shuts down, then it may be."

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.