I was the Bernie Madoff of speculative baby trading until my prize infant gargled horse tranquiliser and died

Stupid, selfish babies.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

In days of old, before mankind had conquered—perhaps destroyed—the natural world, we would attribute the vicissitudes of fate to the will of the gods. If your village was swallowed by an earthquake, your child taken by ague, your crops struck by pestilence, it was because a higher power decided it. The alternative—that these tragedies just happened—was too maddening to accept.

We have no need for gods these days. Now we have Wall Street, whose distant and inscrutable machinations ravage towns, take children, and blight crops far more effectively than the gods of old. We no longer have need for Apollo and Dionysus. Now we have Brad and his MBA. Brad sucks.

Except not anymore. Now I am become Brad, and the universe has unfurled before me like delicious fruit leather. I am the master of Space Warlord Baby Trading Simulator (SWBTS), the new game from Strange Scaffold that invites you to pick a likely-looking baby fresh from the maternity ward and bet on the outcome of their life. Or you can short them, if they seem like the type to lose an arm in a wheat thresher or something like that.

It works like this: SWBTS is divided into a set of campaigns. Each one features a guy—you—of dubious morals and limited seed capital, who has a goal to raise X amount of money in Y number of days. You start out as Pixem, a disgruntled teacher whose life dream is to own (not use, just own) a boat and who has decided to give himself four days in which to achieve that.

Off you go, choosing one of a number of small, glutinous infants to place your bets on. Initially, you've got nothing to aid your decision but vibes. Maybe this baby's mucilage has an appealing hue, maybe this one's name reminds you of a loved one (if that loved one is called "Himpo").

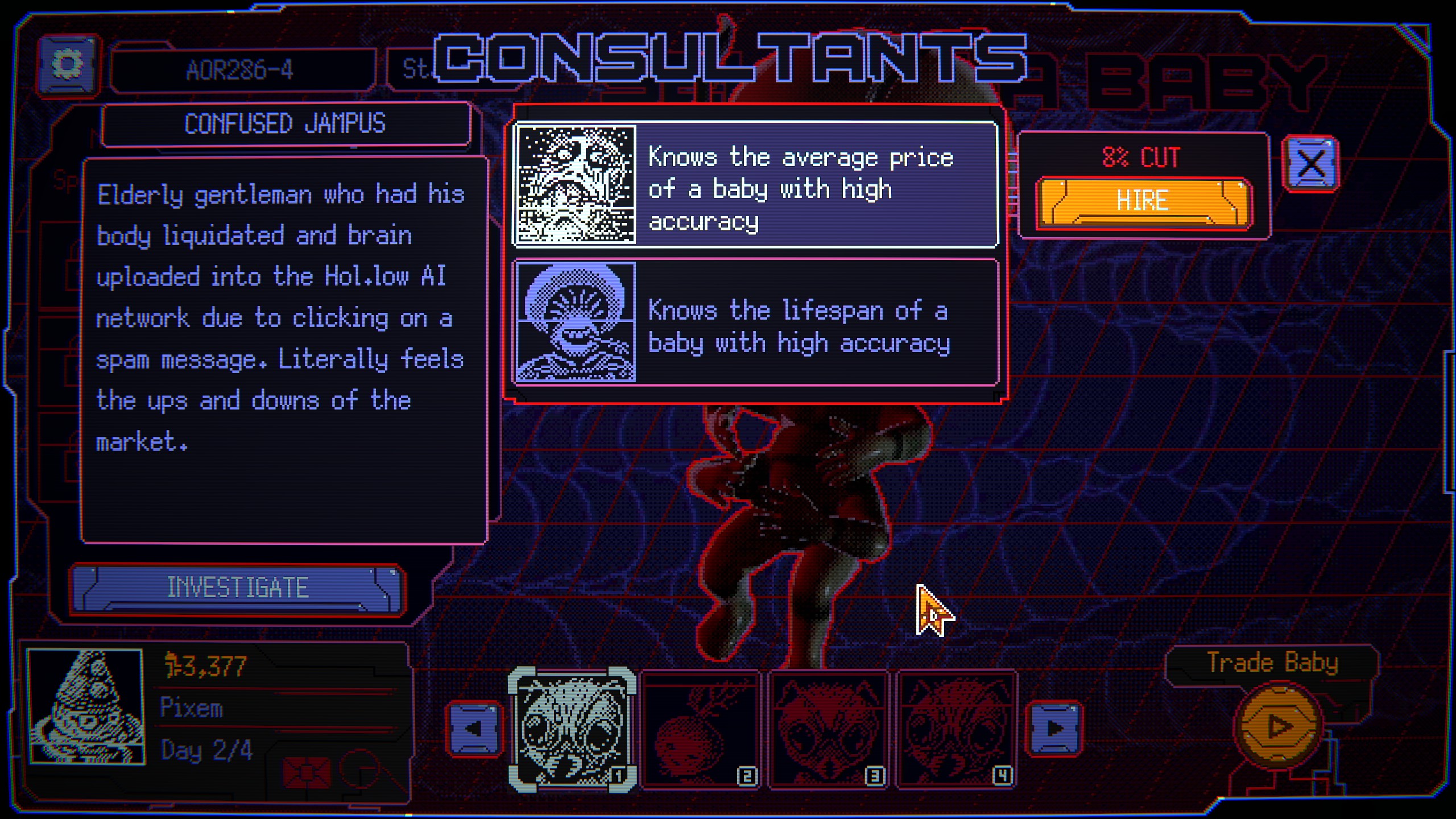

This gets more complex. Before long, the baby-betting screen jostles with potential advisors, who will tell you precious baby secrets in return for a cut of your takings. Is it worth 8% of your take-home to know which two poles a baby's average price will veer between? Is it worth 15% to know, with absolute certainty, that the precious infant on your screen will one day go hiking, or host a potluck, or be assaulted at a peaceful protest?

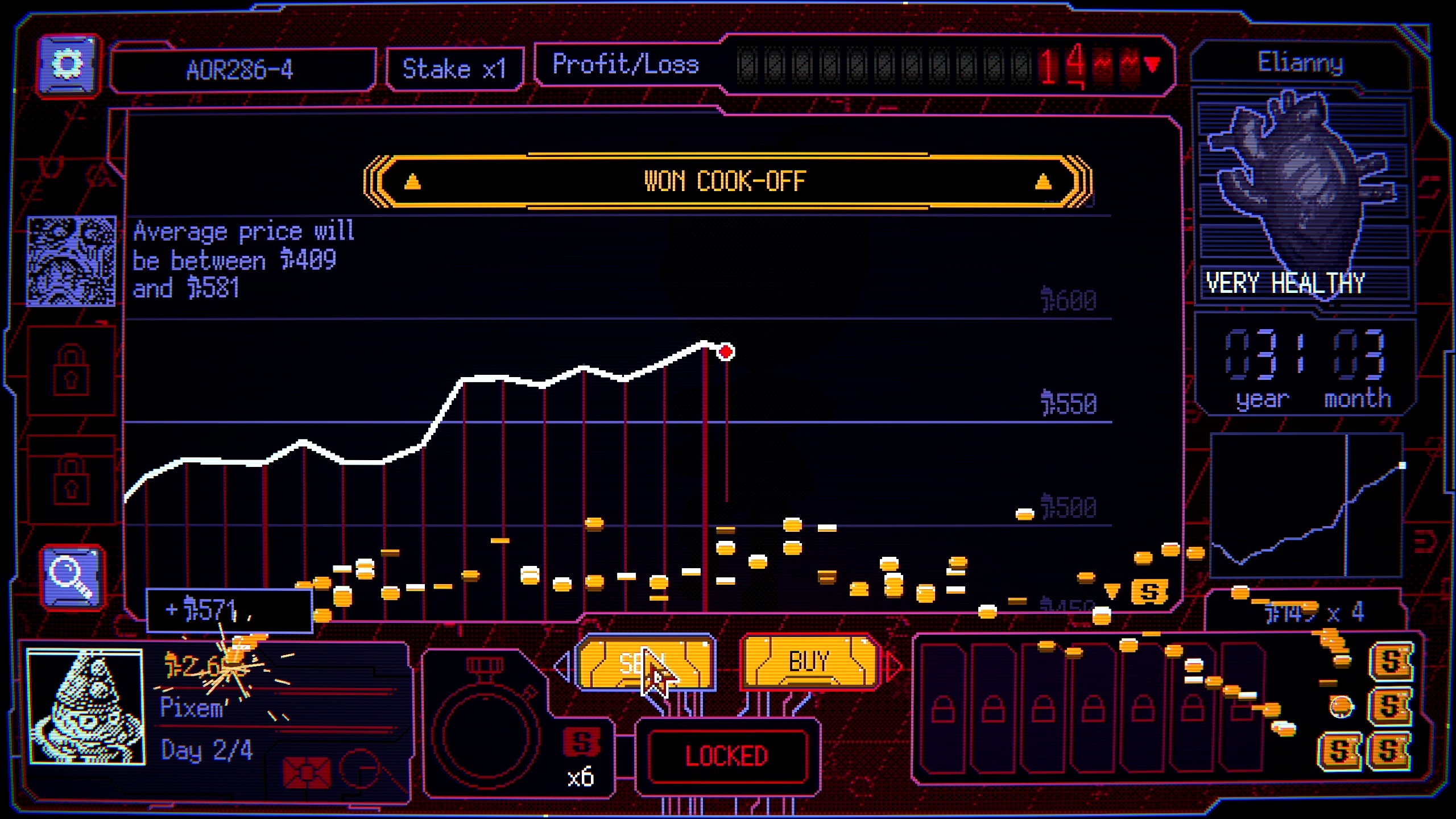

I deemed the answer to that question was 'probably'. Those events are the things that determine your baby's share price. As the years go by, life events both positive and negative will flash up on the screen, each one marking an up- or downturn in your chosen baby's price. Your baby won a cook-off at age 25? Number go up. Your baby's flesh was melted by orbital acids 15 years later? Number go down.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

So having a heads-up as to what kind of nightmares your child (well, not your child, someone else's child to whom you have market exposure) will experience can be handy. It's not just a matter of picking the most blessed bairn, either: a child set for a truly awful life is a good opportunity for a short. That is to say, you wait for a rare good thing to happen to them, begin the short while the stock price is high, then cash out when the inevitable train of maladies strikes, making bank.

It's lucrative and, alas, dangerous. It marked my downfall. I was onto a good thing with a small child who resembled a leek called Lil Bit. Lil Bit's life sucked. He was born, got struck by lightning, had his savings wiped out by a recession (he was six at the time), contracted some sort of exotic disease, and so on. Things turned around for him when he found some clothes in a trashcan, though. That sent his stock price climbing fairly steadily, and I figured it was as good a time as any to short.

I was right, kind of. Lil Bit's life quickly got back off-track. But it got off-track with a bit too much enthusiasm: he gained an eating disorder and then drank horse (or "glepple") tranquiliser, which might be related. Regardless, this killed him.

Ordinarily, that would be fine, but his death voided my short position, leaving me with zero profit and a $7,500 entry fee. Also, a side bet I had made—that his stock price would reach such-and-such a level—failed, leaving me $10,000 in the hole overall. I was bankrupt, and all because this stupid, selfish kid hadn't stuck it out a little longer.

Honestly, it's harder than you think, being rich.

2026 games: All the upcoming games

Best PC games: Our all-time favorites

Free PC games: Freebie fest

Best FPS games: Finest gunplay

Best RPGs: Grand adventures

Best co-op games: Better together

One of Josh's first memories is of playing Quake 2 on the family computer when he was much too young to be doing that, and he's been irreparably game-brained ever since. His writing has been featured in Vice, Fanbyte, and the Financial Times. He'll play pretty much anything, and has written far too much on everything from visual novels to Assassin's Creed. His most profound loves are for CRPGs, immersive sims, and any game whose ambition outstrips its budget. He thinks you're all far too mean about Deus Ex: Invisible War.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.