Can Call of Cthulhu ever be a good videogame?

Why it's nearly impossible to truly capture Lovecraft in a videogame, and how Cyanide Studios hopes to pull it off.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

It is spring and I am in Paris. I am at war with my myself—half reporter, half H.P. Lovecraft fanatic, about to see the most important Cthulhu game of the past 10 years.

The part of me doing my job is sitting with developers from Cyanide Studios to talk about their game Call of Cthulhu, to see what’s unique about it, if it looks promising. They’re friendly, especially lead developer Jean-Marc Gueney. He's lively, and as soon as we start talking about Lovecraft we develop a quick and easy rapport.

The other part of me is on a witch hunt. While prior games emulating Call of Cthulhu have been fun, they haven't captured what makes Lovecraft great. And Cyanide hasn't just set out to emulate Lovecraft. They're making an official adaptation of the Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG, the best game adaptation of Lovecraft ever. The risk is palpable. The Lovecraft fan in me is ready to crucify these men in the most florid prose should they fail my ideological purity test. I pepper them with hard questions (unfair, even) both in-person and later over email.

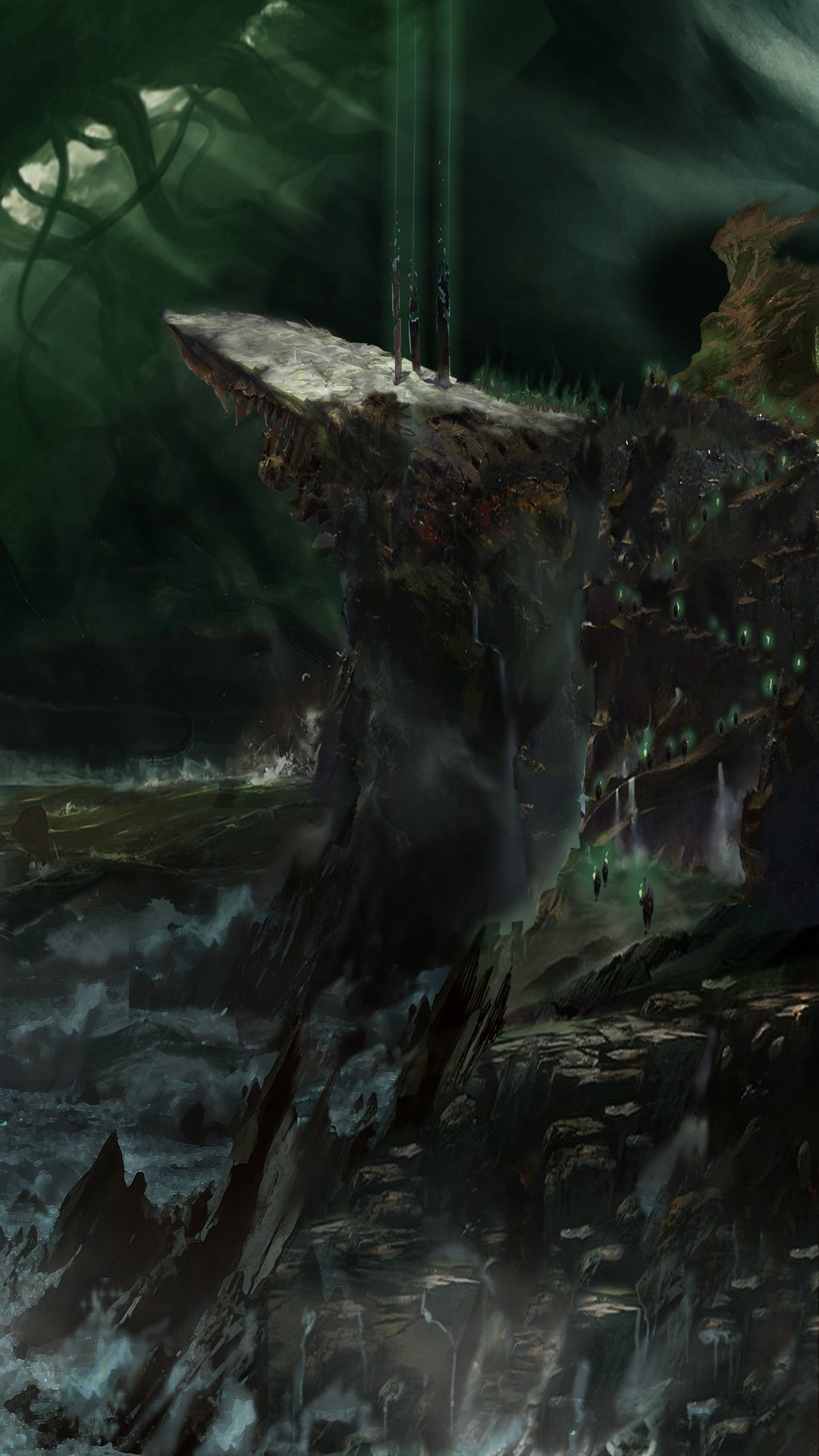

“Call of Cthulhu will be an investigation game with strong RPG elements,” said Gueney. “The hero, Edward Pierce, will have to find out the truth about the death of a famous artist.” Of course, like any Lovecraft story, Cyanide intends for it to get darker from there. The hero will make their way to Dark Water Island, an island off the coast of Lovecraft’s favorite New England setting. They’ll have to use their character’s skills to “discover, explore, and survive” what they find there. Most gameplay will be stealth, investigation, and psychological horror—carefully managing your character’s tabletop-faithful Sanity score.

Cyanide is making an official adaptation of the Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG, the best game adaptation of Lovecraft ever. The risk is palpable.

I fell in love with Lovecraft’s stories as a too-young-for-it kid and never looked back. Lovecraft tickles the intellectual, rational part of your brain into sheer dreadful vertigo. So rarely is Lovecraft’s brand of “cosmic horror” done right in a videogame, truly emphasizing the unknowable, the horrors beyond the firelight of our perceived world.

Rarely does a game manage to adopt the subtle, almost teasing, pacing or delivery that make cosmic horror so good. Call of Cthulhu on the tabletop is one of the few games that gets that feeling right.

I admire game developers who are willing to take on the challenge. I’m just skeptical it’s even possible at all.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The many horrors and many challenges of Lovecraft

Working mostly between 1918 and 1937, H.P. Lovecraft wrote cycles of sci-fi horror stories, and let friends freely play with his characters, in a way that would later on come to be fundamental to establishing the Cthulhu Mythos—one of the first of what we’d recognize as a modern shared fiction world. Modern readers have to work around some of the more objectionable or outright racist parts of his corpus, but his influence in undeniable. Horror and fantasy authors from Stephen King on down have praised Lovecraft in no uncertain terms. Neil Gaiman said that “H.P. Lovecraft built the stage on which most of the last century’s horror fiction was performed.”

To say that Lovecraft’s monsters are “in” right now would be an understatement.

They are flaming hot. Cthulhu, his face-tentacled Great Old One brainchild, has squirmed its way into the permanent pantheon of geekdom. Video gamers are spoiled for tentacular horrors from other dimensions and the accompanying spirals into madness. Every era of World of Warcraft has included at least one section of content themed after Blizzard’s own knock-off brand of Lovecraft. Dark Souls creator Miyazaki’s Bloodborne is rife with Lovecraftian gods. The monster from popular Netflix series Stranger Things may well be a Dimensional Shambler.

But for all this representation, it’s rarely true to Lovecraft’s writing. Lovecraft’s horror is a difficult literary genre to capture because it’s really about a problem with no solution. The desire to explore and rationalize, set against the idea that not everything can be understood or perceived by human beings. In the words of critic Jess Nevins, “What Lovecraft created was a specifically twentieth century idea: the universe as an empty, materialist one, in which there is no spiritual meaning to any actions and in which human existence is not significant in any way.” The title of Nevins’ piece is, in itself, a perfect summation of Lovecraftian cosmic horror’s ethos: “To Understand the World Is To Be Destroyed By It.”

To succeed where others have failed, Cyanide has to somehow capture cosmic horror in a videogame you can win while also living up to the pedigree of Call of Cthulhu, the roleplaying game that turned gamers on their heads when it was released in 1981. Call of Cthulhu encourages you to be afraid. You aren’t brave fantasy heroes or space captains, you’re desperate investigators who’ve stumbled onto something much bigger than themselves. You are probably going to die, or go mad, or both. Your best hope, most of the time, is holding back the apocalypse for just a few more days.

Cosmic horror works well in the lo-fi world of tabletop, where your buddy is using their best, spookiest ghost story chops to scare you. It’s descriptive, slow paced, and allows for a growing sense of dread. Sentences can leave details to the imagination, just as in a written tale. It draws you into an investigative spirit, the same spirit that Lovecraft’s protagonists so often live out their stories in, gathering reams of information until disparate facts form a horrific truth. Call of Cthulhu adventures are often written open-ended, and you’re never sure what the horror is until it’s upon you, but the end is rarely good for the heroes. Digging into the mythos gives you more information, more ways to act and slow down the inevitable—but at huge and horrid personal cost. You literally become irrevocably and permanently less sane.

Videogames tend to get everything wrong that Call of Cthulhu gets right. Game protagonists are tough, hard-bitten people who can handle whatever’s thrown at them and keep on kicking. Alien monstrosities are detailed 3D models: a bestiary of creatures to learn, gawk at, outwit, and kill. They lose the horror of the unknowable. Games like Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth are not cosmic horror, but survival horror. You’ve got guns, and they work. Sometimes the solution really is just blowing up the subway train-sized shapeless horror with dynamite and moving on with your life. The fast pace most gamers expect just doesn’t work for a style where slow, building dread and final, horrific truth are the most satisfying part.

Videogames tend to get everything wrong that Call of Cthulhu gets right.

That’s the legacy of games the Cyanide team has to work from, though. That’s the familiarity that most video gamers have. Despite my skepticism, I feel compelled to let Gueney know we’re working from a similar background. When I mention that I am a tabletop roleplayer, and Call of Cthulhu lover, I have Gueney’s immediate attention.

“I was very young when I first played the Call of Cthulhu RPG,” he said. “From there I wanted to learn more about the author that inspired the game and thus I read his novels. I still play the pen-and-paper RPG today with the [french] 7th edition. The game’s unique feel for both scenarios and characters is still very appealing to me as a player.” When I ask him about their story design, he says that they’ve worked with Mark Morrison—a talented tabletop scenario designer popular among the Call of Cthulhu crowd.

In that case, I think, maybe Cyanide can pull this off.

Jon Bolding is a games writer and critic with an extensive background in strategy games. When he's not on his PC, he can be found playing every tabletop game under the sun.