SpyParty's long journey to Steam

The multiplayer social espionage game that's taken nine years to make, and still isn't done.

Chris Hecker laughs as he recalls an early conversation he had with the founders of Supergiant, back when that studio was beginning production on an action-RPG called Bastion. Hecker was starting work on his game SpyParty at the time, and wasn't sure where to take it, if anywhere. "They've now lapped me three times!" he exclaims, noting they not only released Bastion, but followed it up with Transistor and Pyre while SpyParty remained in its prenatal state.

I first heard about SpyParty in 2009, on a podcast hosted by the editors of 1Up.com. Back then, it was seen as one of the foundational pieces of the indie renaissance—alongside Limbo, Braid, and Super Meat Boy—redefining the nature and economy of game development.

It's been nearly a decade since that moment. 1Up no longer exists, the indie scene has disemboweled and reincarnated itself dozens of times, Phil Fish finished Fez, announced Fez 2, and blew up his studio, and finally, finally, SpyParty is available on Steam. Yes, it is still in Early Access, and yes, 47-year-old Chris Hecker still clutches a list of planned improvements close to his chest.

"It's not relief yet, but there is a certain element of pride that I actually did it," he says. "I pushed the button."

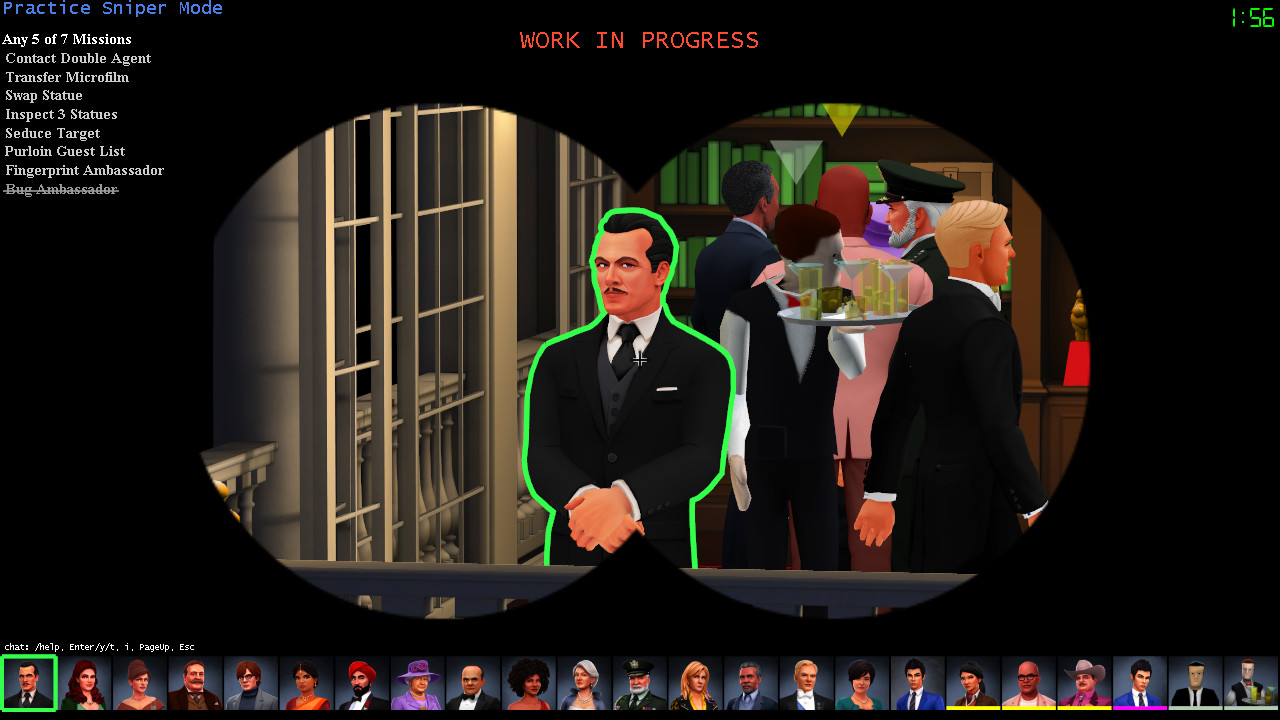

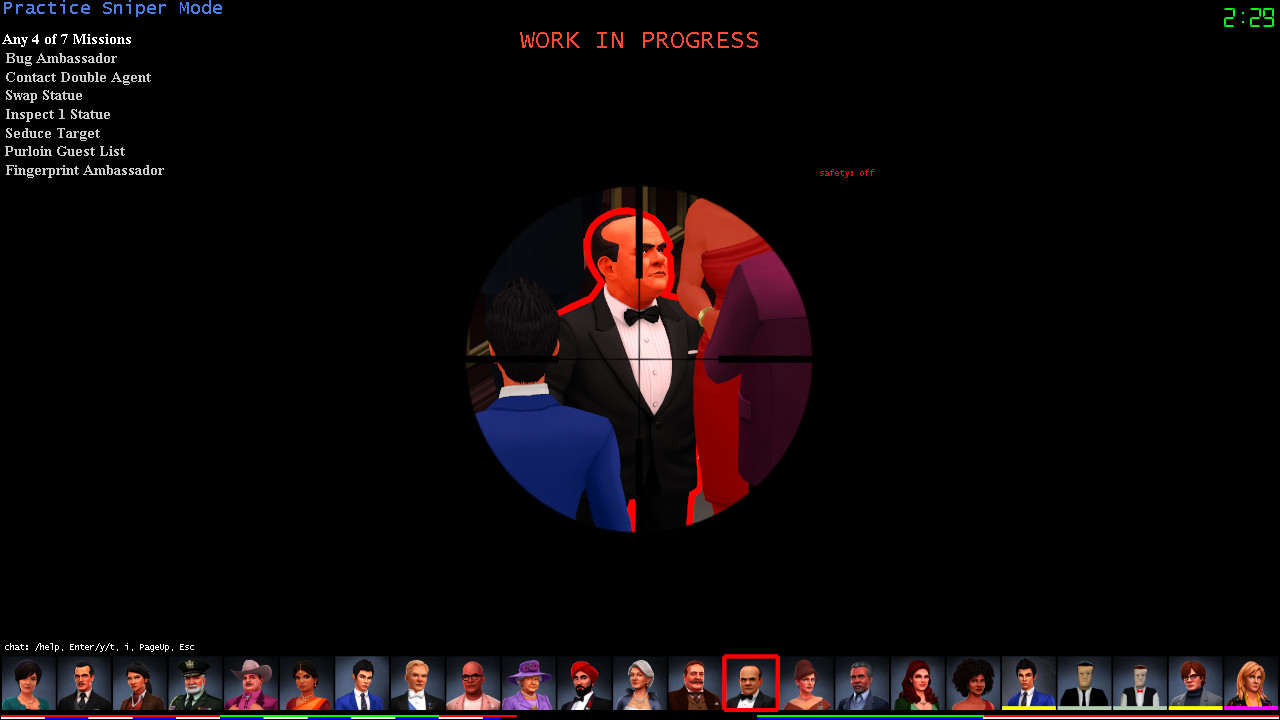

If you're unaware, SpyParty is essentially a game of cat and mouse. One person plays a spy, in the cologne-splashed, Roger Moore sense of the word. They're assigned a number of missions they try to accomplish while blending in at a a glitzy cocktail party. Another player takes control of a sniper with a bird's eye view of the event. They win by putting a bullet through the spy's brain.

That dynamic encourages a metagame where the person playing the spy wants to disguise themselves as a brainless NPC, laughing, dancing, drinking, all pantomimed within the confines of basic AI routines. The sniper, on the other hand, is looking for anyone at the party who looks too smart to be computer-controlled. It's a fascinating multiplayer conundrum that requires an understanding of psychology, rather than marksmanship, speed, or superior talent-tree builds.

Hecker is just as in love with the design today as he was 10 years ago. "For whatever reason I had infinite endurance to work on SpyParty," he tells me. "I want to keep working on it until it's perfect. I don't get bored with things. My job is different every five minutes. You're working on a 3D competitive online game with 30 animated characters. There's a lot of stuff to do. I can be a networking programmer, I can be a designer, I can be a marketer, I can do PR… I'm just lucky."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

To be clear, SpyParty has been available in some form over the course of its protracted development. First as a closed-beta shipped out to hungry email accounts, then as a for-profit open-beta available from the website. Over the course of those nine years, Hecker has never been afraid of people beating him to the punch. Sure, Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood took a crack at the concept with its tacked-on but surprisingly fun multiplayer mode (in which assassins attempt to stab each other on cobblestone Italian streets full of innocent bystanders dressed just like them). There was also The Ship, originally a Half-Life 2 mod, and Murderous Pursuits by the same team. However, Hecker was always secure in the knowledge that SpyParty was a difficult game to make—a delicately poached egg of an idea that takes a little bit of madness to get right. No major publisher would rip him off; they simply wouldn't want to take the risk.

I can program a computer in the Bay Area, I'm not gonna starve to death. Like, 'Oh, I have to suffer and go make hundreds of thousands of dollars at Facebook.'

Chris Hecker

So how did Hecker manage to stay afloat for the past decade? How could he afford to take a Duke Nukem Forever amount of time to create his cloak-and-dagger masterpiece? Simple. The last project he worked on before SpyParty was Spore. His career at Microsoft started in the '90s, and ended after 2008 when Will Wright's ultra-hyped, ultimately flawed universe simulator hit store shelves. Once he left the company, Hecker tells me he had a couple hundred thousand dollars in his savings account, as well as a low-mortgage house in the Bay Area that he describes as the "perfect indie situation." It was more than enough to subsist on through SpyParty's development, though Hecker tells me at the tail end, he did borrow some money from his mother to push through the final thresholds.

"I spent my daughter's college fund and all my life's savings, the last couple years was kinda like 'Woah, what am I doing here,' like, 'All right I guess I'm burning all of this down,' there was a lot of anxiety which is distracting from actual development," he says.

Hecker has absolutely no delusions about his privilege. He knows that most indie developers don't have swollen coffers from a senior position at a legacy company like Microsoft, nor do they have family members willing to throw money down the rabbit hole. SpyParty is currently paying him back, of course, but even if it didn't, Hecker would've been fine. "I can program a computer in the Bay Area, I'm not gonna starve to death," he laughs. "Like, 'Oh, I have to suffer and go make hundreds of thousands of dollars at Facebook.' I'm not mining coal at that point. There's a backup plan of just, 'Get a job,' but it's looking like I won't have to."

It's awesome that SpyParty is finally on Steam, and it's awesome that Hecker finally gets to reap the rewards of a decade's worth of hard work. SpyParty is his dream project. He's not sick of it in the slightest, nor does he yearn to escape into the next idea. It's an obsession that's paid off, and it makes you wish other creatives were afforded 10 solid years to perfect something they love.

"I had this idea for this thing, this concept, of a multiplayer game about subtle human behavior," says Hecker. "For whatever reason, someone upstairs wanted it to work incredibly well. My top players have 20,000 games played, and they're playing the game I made, it's not like at that high-level they're playing a different game, it's still this highly asymmetric game about subtle human behavior. It's awesome, it's great to see people do that, and they're so much better than me it's not even funny."

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.