Why critics love Mountain, but Steam users are calling it "worthless"

According to The Atlantic , Mountain “invites you to experience the chasm between your own subjectivity and the unfathomable experience of something else.” It “hypnotized” the Los Angeles Times , and The Verge called it "the only experience that has ever made me feel sad about a geological phenomenon." Meanwhile, on Steam, user reviewers are gushing: Mountain is “worthless,” “just a screensaver,” and “a fucking joke.”

There are positive Steam reviews, too, but many are facetious. Some customers are irate. Why the hell is the media so fascinated by this $1 game which advertises “no controls"—a game about a mountain that listlessly spins and talks about its feelings and collects detritus with little regard for the player? How is that interesting, or even a game , or worth any amount of money?

I've been running Mountain for two days now, and I'm not spilling over with praise for its ambient melancholic introspection. It's not brilliant, but I like it. I like it because it can't be described as “solid,” “visceral,” or “deep.”

Those words are ugly shorthand writers use when they're tired of describing complex things, or don't understand them. Controls are “solid,” combat is “visceral,” customization is “deep”—I'm sure I've been guilty of using them all (shame on my family). It isn't good writing, but sometimes it's hard to get excited about the umpteenth iteration of 'the sniping mission.' In a state of fatigue, limp clichés are easy and comforting. “Look, we all know what this is,” they say, “So let's just agree that it's fine and move on.”

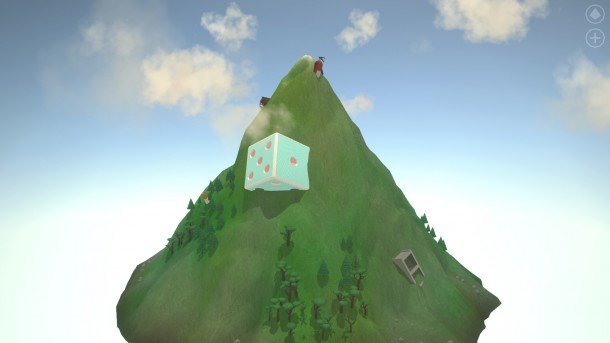

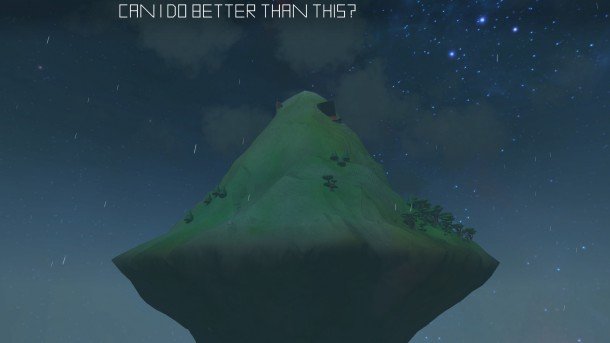

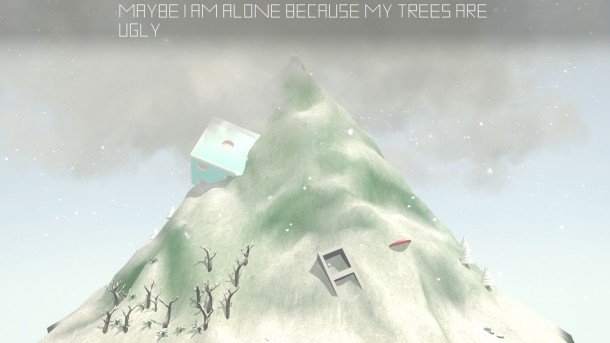

But then there are games like Mountain. It's just a damn mountain. It's a damn mountain that spins around and comments on the weather, and makes me feel a little sad sometimes. Why do I like that spinning the mountain quickly makes clouds disappear? Why did it make me happy when I noticed my mountain, buried under two other open windows, contemplating its existence after two hours of ignoring it? Does it even make sense to enjoy a game which will “play itself?”

Mountain isn't in an established genre and there's no agreed-upon measurement for its success. There's no lexicon of words like “tactical” and “immersive” to consult. Writers like it because it hasn't been written about yet. Writers are looking for a story, and Mountain is a new story. It's critically relevant , like an unusual pop music trend.

Assassin's Creed isn't critically relevant anymore, according to Graham Smith's recent editorial on RPS , which also compares games to music. Smith argues that when innovation becomes iteration, as it does over seven years of sequels, critics become “stenographers” who write “patch notes” for each new game. Assassin's Creed isn't bad for gaining loving fans and losing its novelty, he says, but “should take up its residency in Las Vegas.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I don't totally agree—I think there are new thoughts to be had about Assassin's Creed—but I feel Smith's sentiment. Any observation I make about Assassin's Creed today is a growth on a tremendous mass of existing thoughts about Assassin's Creed. If I meditate on wrist blades long enough, I can construct a distinct, probably granular, observation, but day-to-day coverage is iterative criticism on an iterative series.

Mountain, on the other hand, is effortless stimulation. Instead of “how do the controls feel” or “has the stealth gameplay improved,” it's all new thoughts about a more exciting question: “Does this matter?” The answer might be yes, but it might also be no. We don't have years of iteration to tell us whether or not Mountain is important. That's invigorating, but it's also why buyers might feel duped out of a dollar, and they have every right to feel that way.

Dismissing Mountain as "a screensaver” is a valid criticism from a consumer with perfectly normal expectations about what a game should be. I don't fault anyone for being disappointed by Mountain. It has no win or fail state—it's only a 'game' because calling it an 'ambient interactive experience' feels ostentatious. But the writers praising it, myself included, don't see Mountain solely as a $1 entertainment product: it's a story about subverting game conventions, and the animator who worked on Her, and emotion, and big questions about existence and computers and mountains. It might even be more interesting to talk about than to play, and maybe that's the point, and— see ? Now I'm doing it.

Gone Home and Papers, Please were also highly praised, and I don't fault anyone for finding my fascination with them specious, either. Call me a hipster, but as indulgent as it may seem to gush over oddities which attract much smaller audiences than aliens and assault rifles, they are avant-garde. I've written about bullet physics hundreds of times, but existentialist mountains are new. Unusual games stimulate new thoughts about the medium, and they're fun to write about, and that's why they get written about—even when they irk consumers.

Not every consumer, naturally. A bunch of positive Steam reviews have popped up since I started writing this yesterday, and those that aren't jokes express a lot of appreciation. “It's not going to change the industry,” writes one reviewer . “But if most developers started thinking outside the box, like David O'Reilly did here, we could finally play something really new.”

I'm not sure yet where I stand on Mountain, but I like poking at it. It's a genuine attempt at something new—artsy, maybe, but not cynical or insincere—and the opportunity to share my feelings about it is worth $1 to me. I bought copies for a couple friends so we could swap screenshots of our mountains' thoughts, and it's fun. Instead of arguing about the definition of 'game,' we're playing with a new idea, celebrating that there are weird interactive things on the PC, whatever you want to define them as.

The new and weird will always be darlings to a media in search of critical relevance, for however long they stay new and weird and relevant. When they turn out to matter, like Assassin's Creed has, they're celebrated and sequelized and replicated for ages. Otherwise, they're fads, and they go away. It's natural selection, and on this lively platform full of new ideas, it happens fast and it's exciting to be a part of. Rather than rushing to disqualify anything that doesn't fit into existing genres, let's enjoy figuring out if it matters first—even if that means playing a couple “screensavers” now and then.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.