What 4,000 hours of Kerbal Space Program taught this father about space, engineering, and passion

Daniel just wants to go to space, but this 39-year-old father of two will settle for an evening building rockets instead.

In the three years after Kerbal Space Program officially launched on Steam, Daniel 'ShadowZone' spent a cumulative 166 days playing it. That kind of streak feels right at home in the endless multiplayer battles of DOTA 2 or MMOs like World of Warcraft. But to spend 4,000 hours playing a singleplayer space simulator seemed impossible to me. When I first spied the 39-year-old father of two discussing his playtime on Twitter, I wanted him to answer one simple question: What do you even do in Kerbal Space Program for that length of time? Well if you're Daniel, you spend it building staggeringly complex machines to then launch on missions so daring it'd make Arthur C. Clarke sweat—all while rediscovering that childish sense of wonder that makes space so captivating to begin with.

I could build these cool things, but I was not content with just looking at them in the hangar. I wanted to see them in action. That gets complicated and then things explode.

Daniel

"I'm kind of a space nerd—I always have been," Daniel tells me over Discord. "That's been my drive that made me stick with this game. It's not easy, though. I could build these cool things, but I was not content with just looking at them in the hangar. I wanted to see them in action. That gets complicated and then things explode. Sometimes it's fun, but sometimes it's really frustrating."

Daniel shared his forays into Kerbal Space Program's miniaturized homage to our solar system on YouTube. He tells me that his channel first started gaining traction when he published a video showing off his to-scale build of Mass Effect's Normandy spaceship complete with modeled interior and functioning escape pods (just in case the Collectors invade). Since then it's been a slow burn as his ideas have gotten even more ambitious, sometimes with nearly catastrophic results.

In space no one can hear you scream…

...But I'm pretty sure Daniel's wife and children have heard him now and again. His videos don't prop him up as a master Kerbal Space engineer, but more often play out like a sizzle reel of constant failure that documents his numerous attempts to get one of his rockets off of the launch pad. Suffering through Daniel's failures is worth it, though. Not just because I love the way he fills the long stretches of silence as his rockets perform elaborate stage separations with theatrical commentary, but because there's always that moment late into most videos when, seemingly against all odds, things finally work.

As the years have gone by, the missions Daniel has embarked on have gotten only more and more intimidating. He tells me the story of one of his first builds, a battlecruiser, that he finally got into space and then, on a whim, decided to try to get it to one of the most distant planets in the system. "I just fired up the engines and went for it," he tells me. Miraculously, Daniel made it. He was surprised by how strongly he felt a sense of pride and accomplishment in what he had just done. It was a feeling that he wanted to chase.

Compared to his more recent projects, that meager battlecruiser looks like the German V-2 rocket next to the engineered glory of the recently launched Delta IV Heavy. Take his Ozymandias series, for example, where Daniel tasked himself with building a mega-ship that could take him to the Kerbal equivalent of Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and their respective moons. "It was a really complex mission in regards to planning and dealing with all the logistics," Daniel tells me. "I'm really proud that I was able to pull it off."

Though the original version of Kerbal Space Program doesn't include these worlds, Daniel used the Outer Planets mod to add them in and then set his sights on landing an intrepid Kerbal (the tiny humanoids that pilot these ships) on each of these 17 new planets and moons.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

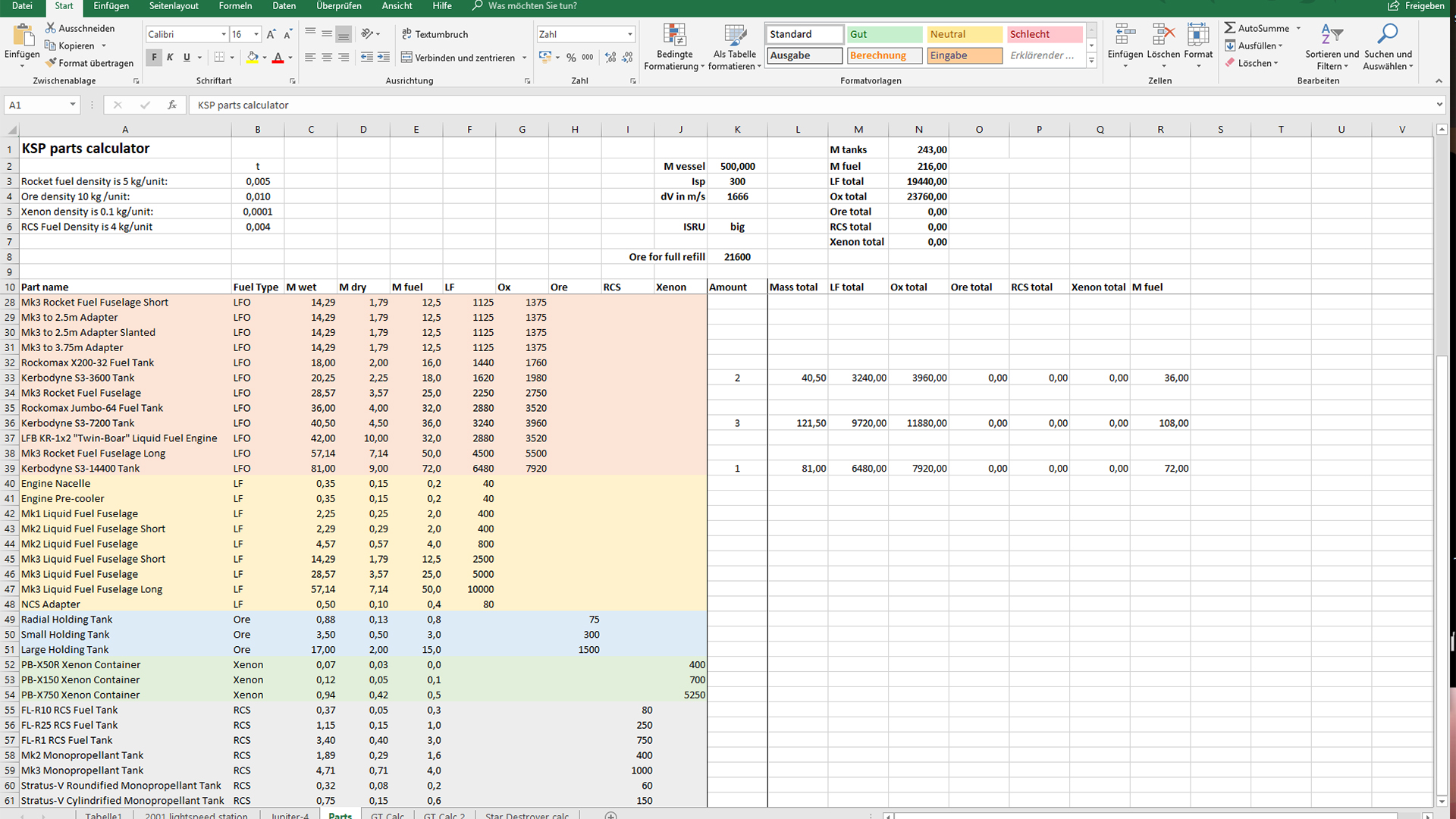

It's hard to overstate what an enormous challenge this was. First, Daniel had to design and engineer a ship that could escape the gravitational well of the planet Kerbin, where his space center is located. That would be easy if this were just any old rocket, but Daniel needed one that could also hold a crew of ten Kerbals while fitting enough fuel reserves to handle each of the burns he'd need to realign the rocket and get it into orbit surrounding each planet and back home. "There are a few mods that help you with building, like Kerbal Engineer Redux," Daniel explains. "But in the end you have to do the math yourself. You have to calculate [by hand] if you can make that burn to the next planet. Will you have enough fuel? Will the lander have enough thrust to get back into space?"

For that, Daniel uses an Excel spreadsheet to handle everything—making Kerbal Space Program officially the second space game to require knowledge of Excel to play competently. "Planning it took weeks because I only have a limited time of when I can play and how long I can play—a few hours maximum every day," Daniel explains. Having to juggle the responsibilities of being a good father, husband, and having a full-time job at a software development company means Daniel can only play rocket scientist in the evening after the kids are sleeping. During those few pockets of play time, the Ozymandias went through eight disastrous iterations before Daniel finally designed one that could carry the required amount of fuel and adequately escape Kerbin's atmosphere without destabilizing and violently exploding. He was finally ready to begin the mission.

If you've never played Kerbal Space Program, it's important to understand how much reverence it has for simulating the natural laws that govern real-world space travel. Simulated forces like wind resistance, gravitational pull, and thrust all have to be accounted for when designing a shuttle. And once you get the damn thing into space, even the slightest human error can be disastrous—just like in real life. It's not rocket science, but it is damn close.

In the end you have to do the math yourself. You have to calculate [by hand] if you can make that burn to the next planet.

Daniel

Daniel spent weeks of his life perfecting all of that math, mapping orbital trajectories to slingshot the Ozymandias from one planet to the other. "There's this excitement when you try something out that you've worked on for a really, really long time," he says. "You have it on the launch pad for the first time and you hit launch, and all that anticipation that has built up. There's this feeling of trepidation, and then relief and excitement when you realize—yes, this is going to work!"

That feeling of relief was short-lived, though. After reaching the ringed planet of Sarnus, Daniel prepared for his most difficult descent of the whole journey to a moon called Slate. First he had to save-scrub through a few disastrous landing attempts, but then he realized that he had made a miscalculation during his planning phase and his lander didn't have enough fuel to reach a high enough orbit around the moon for pickup. No autosave was going to help him avoid that blunder. For the lone Kerbal on board, death seemed inevitable.

But then Daniel tried something truly audacious: Using the Kerbal's suit thrusters, he had just enough fuel to push it into just the right orbital trajectory that a rescue mission using the Ozymandias was possible. Though it lacks a lot of the tension, the rescue is like something ripped straight out of Andy Weir's novel, The Martian. I point that out to Daniel and when he tells me he has another series where he recreates the exact circumstances and journey of the fictional astronaut Mark Watney, I burst out laughing.

His next mission is even more ambitious. Daniel is recreating 2001: A Space Odyssey shot-for-shot using his whole to-scale models of the ringed space station and the Discovery One spaceship. Like everything Daniel attempts, it hasn't been easy. Getting structures of that size into space has proved daunting, but he's making good progress.

"There's a saying: Space is hard," Daniel says. "And I think Kerbal Space Program captures that perfectly. Even though it's a lot easier than real-world space exploration is, the challenges are real. You really have to think about things like payload fractions and thrust-to-weight ratios. There is actually a small part of physics that you have to comprehend in order to make anything work. You have to understand that you need enough thrust to get this thing off of the planet. You have to understand that an orbit is basically shooting stuff in space and then keeping it at a velocity so it doesn't fall back down."

The sincerest form of flattery

All that time that Daniel spends playing astronaut in front of his computer isn't just idle fun, though. He tells me that it comes from a deeply rooted fascination with the mysteries of our universe and humanity's attempt to unravel them. A few days ago, Daniel was watching a video on the popular YouTube channel Smarter Every Day. The host, Destin Sandlin, had been invited by the United Launch Alliance to film the rollback of the Delta IV Heavy rocket that, on August 12, launched the Parker Solar Probe toward the sun. During that video, Sandlin asks about the message printed on the side of the Delta IV Heavy that reads "In memory of Andrew A. Dantzler." United Launch Alliance CEO Tory Bruno tells Sandlin that Dantzler was the one who came up with the complex trajectory the Parker Solar Probe would use to reach the sun. "Without him, we would not be standing here today," Bruno says.

Later in the video, Bruno expands on that sentiment: "When we're launching a mission like this, the Parker Solar Probe, this is someone's life work … That's a pretty big responsibility and it weighs heavy on our guys." Daniel says Bruno's response deeply resonated with him—not because the 166 days of his Kerbal space career compares to the achievements of these engineers and scientists, but because Kerbal Space Program opened his eyes to what an enormous challenge exploring space really is. He's felt the crushing defeat of watching weeks of effort evaporate into flames mid-flight. How much more painful, then, when those flames consume your entire life's work? "They have worked decades on perfecting the science and testing their hypothesis and its culminated in this spacecraft," Daniel explains. "That really stuck with me."

Space is hard. And I think Kerbal Space Program captures that perfectly.

Daniel

Kerbal Space Program is a window that gives Daniel a view to a whole universe he'll never be able to explore. But it also gives him a deeper sense of gratitude for those who do. "My parents took me to Kennedy Space Center back in the early '90s," he recalls. "I was 11 back then. And it's still a vivid memory to me. There was this gigantic crawler for the space shuttle and we stood in front of that, and 11-year-old me looking at that thing I was like, how did they even build that?"

That profound moment has stayed with Daniel all his life, but growing older has a way of dulling what used to fill us with wonder. Despite always having an appetite for science fiction, it wasn't until Daniel booted up Kerbal Space Program for the first time that he reconnected with that restless sense of curiosity about our universe. "Kerbal Space Program reminded me again of my passion for space," he says, confessing to me that, as silly as it may be, his greatest dream is to go to space himself one day. "I'm well aware that since I'm neither an astronaut or rich it probably won't happen in my lifetime. But one can still dream."

Short of winning the lottery or being involved in somehow goofier real-life version of the movie Armageddon only with software developers instead of oil drillers, I don't see it happening. But I love that, despite being a game about launching silly green humanoids into space, Kerbal Space Program can nurture that kind of passion. It's wonderful that even though Daniel might never perform a spacewalk high above our own blue planet, he can still live out that dream in the quiet hours of the night… after he's put the kids to bed, of course.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.