Why Elon Musk's plan for global internet access annoyed astronomers

Starlink is promising, but not without its problems.

This article originally appeared in issue 350 of our glossy magazine. You can get it delivered right to your door by grabbing a subscription, which will also net you special subscriber-only covers.

I've been itching for the chance to write about space lasers, and now that glorious time has come. Oh, happy day! Space lasers!

Satellite broadband has been around for a while and is popular in extremely rural areas far from cable connections. It’s not the fastest, delivering up to 20Mbps according to Which?, and with a killer combo of high latency and low download limits. Starlink appears to massively improve on this, if it lives up to Musk’s promises.

These particular space lasers belong to Elon Musk, the South Africa-born entrepreneur who has a reputation for being, shall we say... a touch eccentric. When not sending cars into space he's been busy recently, not just becoming a father but setting up his Shanghai 'Gigafactory' to produce Tesla cars and launching up to 60 satellites at a time on top of SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets to create the Starlink constellation, which when complete will wreath the Earth in thousands of satellites, providing broadband internet access and communicating with lasers. In space. Space lasers. Yeaaaah!

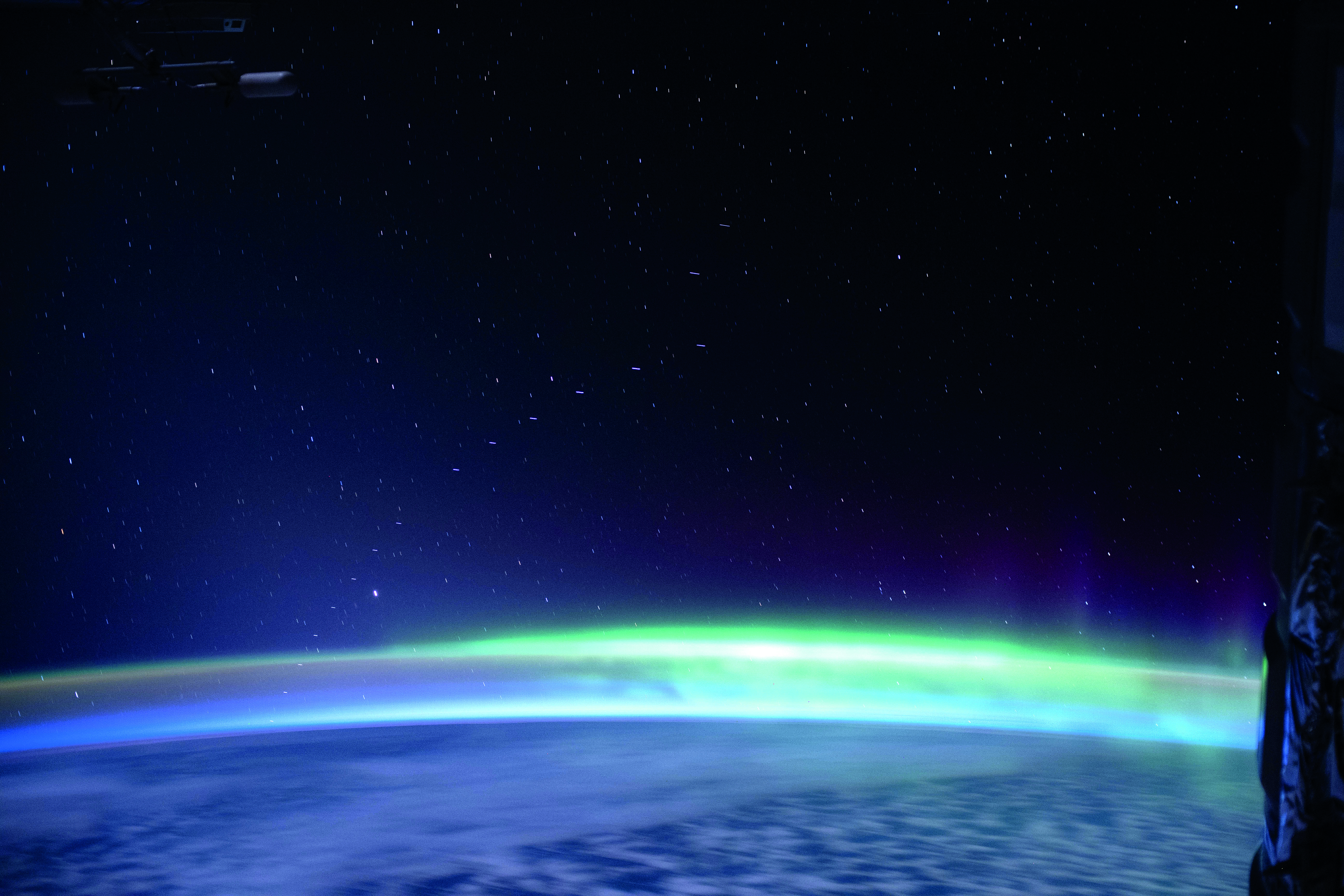

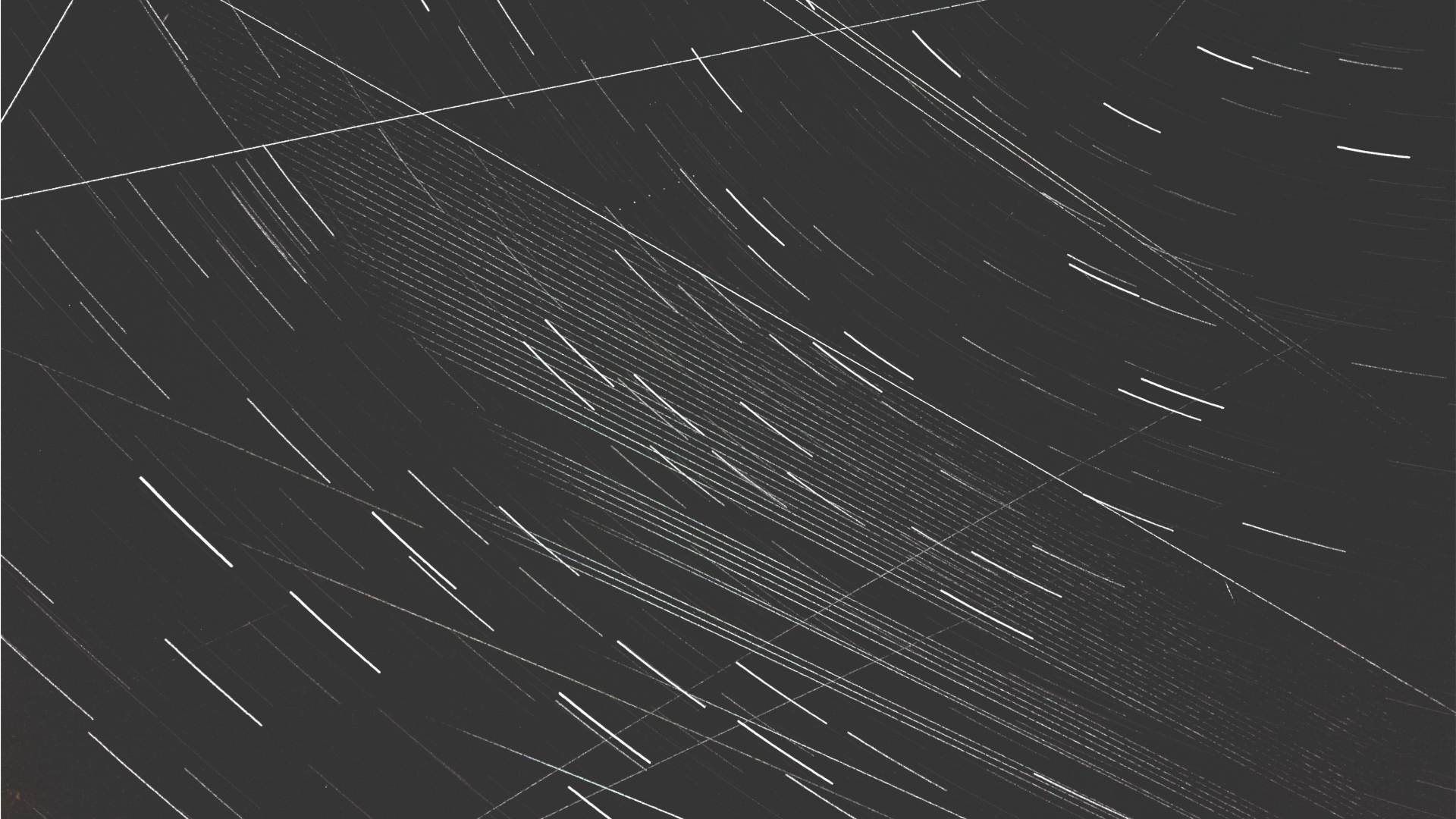

OK, so it's not Moonraker, although some wags have mentioned the similarities between Musk and certain Bond movie characters. We have seen absolutely no evidence that he even owns a white cat. He is, however, seen as a villain by some astronomers and astrophotographers, who fear the constellation, which could grow as large as 12,000 satellites in three orbital shells, could block their views of the night sky. Photographs have already been taken that show Starlink interfering with views of the void, and there are fears that it could grow much worse.

Light reading

So is losing the ability to photograph the stars in the night sky worth the trade-off for convenient, satellite-delivered broadband? And will the connection be any good for gaming anyway? We're starting to get an idea.

Beta testing in August using only a partial constellation generated download speeds up to 60Mbps and uploads of up to 18Mbps. Since then it has stepped up a notch, "Super low latency and download speeds greater than 100Mbps," proclaimed the Starlink Twitter account following further tests at the beginning of September.

This sounds promising, though makes no mention of the upload speeds that are more important to online gamers than they are for general internet surfers. The US Air Force Research Laboratory was able to demonstrate a link of 610Mbps between Starlink and a moving aircraft in 2019, so we know there's more fatness in them there pipes. Sixty of the satellites should be able to handle a terabit of bandwidth.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Latency should be well within gaming limits thanks to the satellites' position in low Earth orbit (LEO). This is an altitude of 1,200 miles or less (for context, the ISS orbits at about 250 miles up, GPS satellites are at 12,540 miles, and a satellite in geostationary orbit, where it always stays above the same part of the Earth's surface, is 22,236 miles up—examples include the Astra satellites used for digital TV).

Each satellite is essentially a flattened wi-fi router with a whacking great solar panel.

As the signal carrying your data travels at the speed of light, we're looking at just six milliseconds to get up there, then the same down again, plus a bit for processing. If you're aiming for less than 100Mbps latency, then Musk may have you covered. It's not just gamers who worship low ping, high-frequency financial traders like it too, and they're prepared to really pay for the privilege, so expect the gaming services and provision of high-speed internet to areas of the Earth currently underserved in that area to follow in the stock markets' wake.

Thanks to their low orbit, Starlink satellites appear to move when observed from the surface of the Earth, and the base stations need to move to track them. These stations, described as a "UFO on a stick" by Musk after a clever data-miner pulled some now-deleted images out of the source code of the Starlink website and posted them on Reddit, just need to be plugged in and pointed at the sky. The instructions, Musk notes "work in either order". In March, the FCC gave SpaceX permission to deploy up to a million of these ground stations, which are only about half a metre across.

Throwing shade

This low orbit is also part of the cause for the satellites' extreme shininess, brighter than 99 percent of existing objects in orbit, which is currently enraging astronomers. They're made of shiny metal, and there are a lot of them. One satellite, dubbed 'Darksat' was launched with a special coating that absorbed 55 percent of the light that hit it rather than reflecting it, but it was abandoned after becoming too hot.

A second experiment, 'Visorsat', has a fold-out visor, transparent to radio waves, that should shade the satellite's antennas from sunlight, reducing the amount they reflect. As for the lasers, well, they're coming. Early satellites launched without lasers, and testing of the system only began as I was preparing this article, with two of the craft successfully firing their prototype lasers.

Once it's added to the whole fleet, the satellites will have a high-bandwidth line-of-sight system to directly link two or more satellites above specific base stations, rather than hopping the signal between neighbouring birds, as happens at the moment. Each satellite is essentially a flattened Wi-Fi router with a whacking great solar panel sticking up from its back. A roll manoeuvre, using the satellites' thrusters, has been proposed to angle the flat surfaces away from the sun, reducing the glare from reflections further.

"Like many astronomers, I am very worried about the future of these new bright satellites, but I'm looking forward to productive conversations between astronomers and SpaceX," says Megan Donahue, president of the American Astronomical Society. "I fully expect that we will come up with creative solutions. I think it's commendable and very impressive engineering to spread the information and opportunities made possible by internet access."

Worldwide internet access is a laudable aim, and perhaps Musk isn't so much of a villain after all. However, one of the mounts that connects the Starlink base station to your house is called the 'Volcano mount', so the possibility of a hidden base full of henchmen is still there.

Ian Evenden has been doing this for far too long and should know better. The first issue of PC Gamer he read was probably issue 15, though it's a bit hazy, and there's nothing he doesn't know about tweaking interrupt requests for running Syndicate. He's worked for PC Format, Maximum PC, Edge, Creative Bloq, Gamesmaster, and anyone who'll have him. In his spare time he grows vegetables of prodigious size.