This confounding game is chess, but with gravity

Professor and experimental game creator Pippin Barr made the best and worst new version of chess.

University professor Dr. Pippin Barr has made the version of chess they play in hell, and I love it. All conventional strategy is gone and every time you think you've found an opening, something confounding happens and it crumbles in a couple moves.

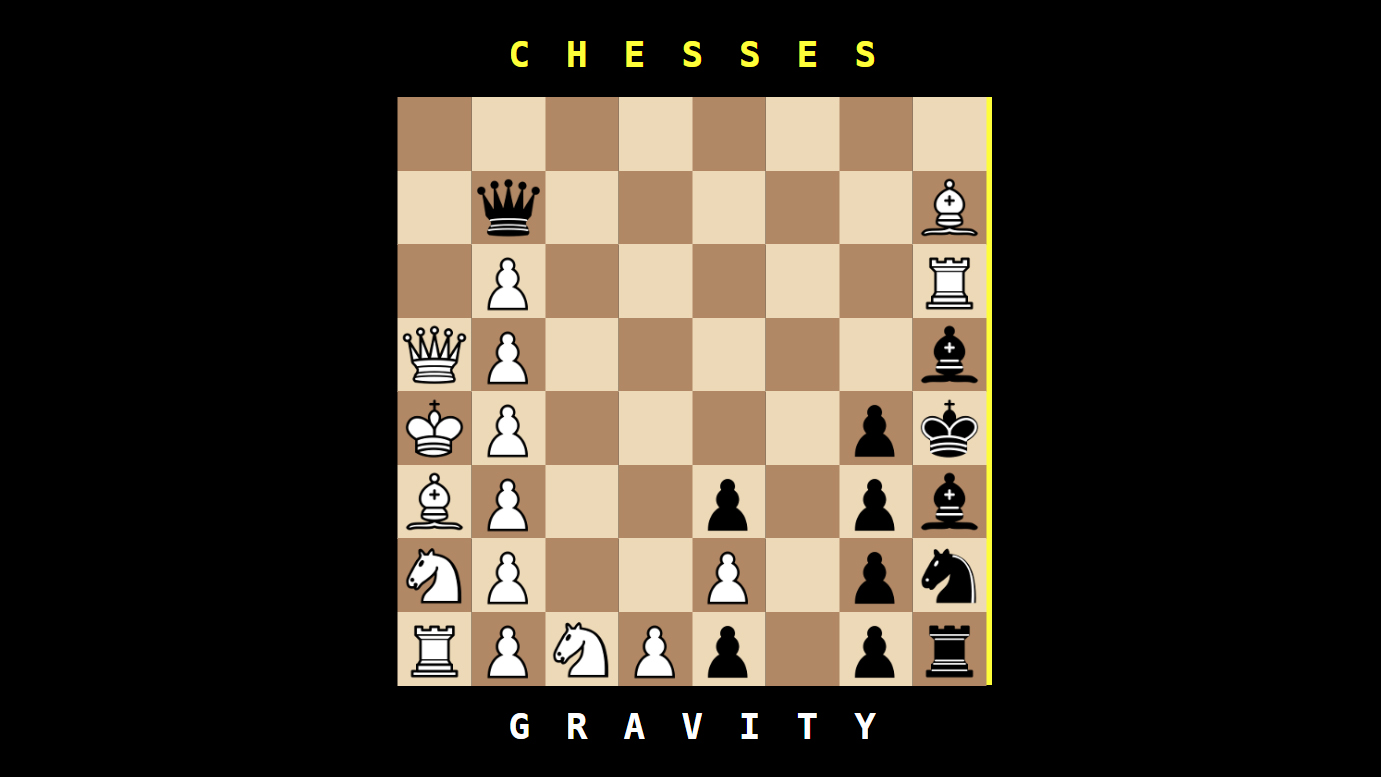

Gravity is part of Barr's latest browser game, Chesses, which includes several chess variants. In Gravity, the board is arranged like a normal chess board (rotated 90-degrees), but the pieces fall to the 'bottom' when there are no other pieces supporting them. If white plays a pawn first, for instance, it will immediately drop to the bottom of the board, and the row of pawns will drop by one, exposing the top rook.

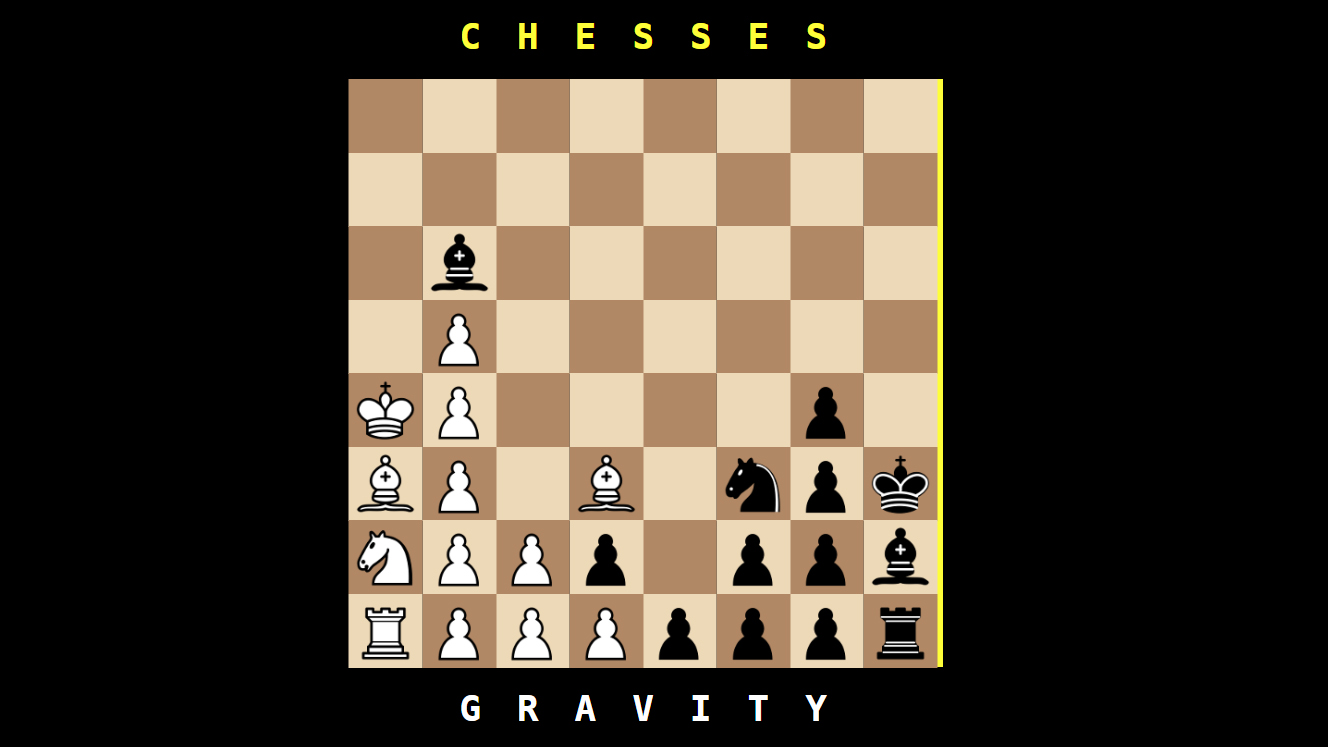

There's no AI to play against, but I've been playing against myself and the situations I'm able to put both sides in are bizarre. Take the scenario pictured below. What is white to do? They can't move any of their pawns in the second row, because that would cause black's bishop to drop one space and check their king. Black has protected the same board position on their side with a knight.

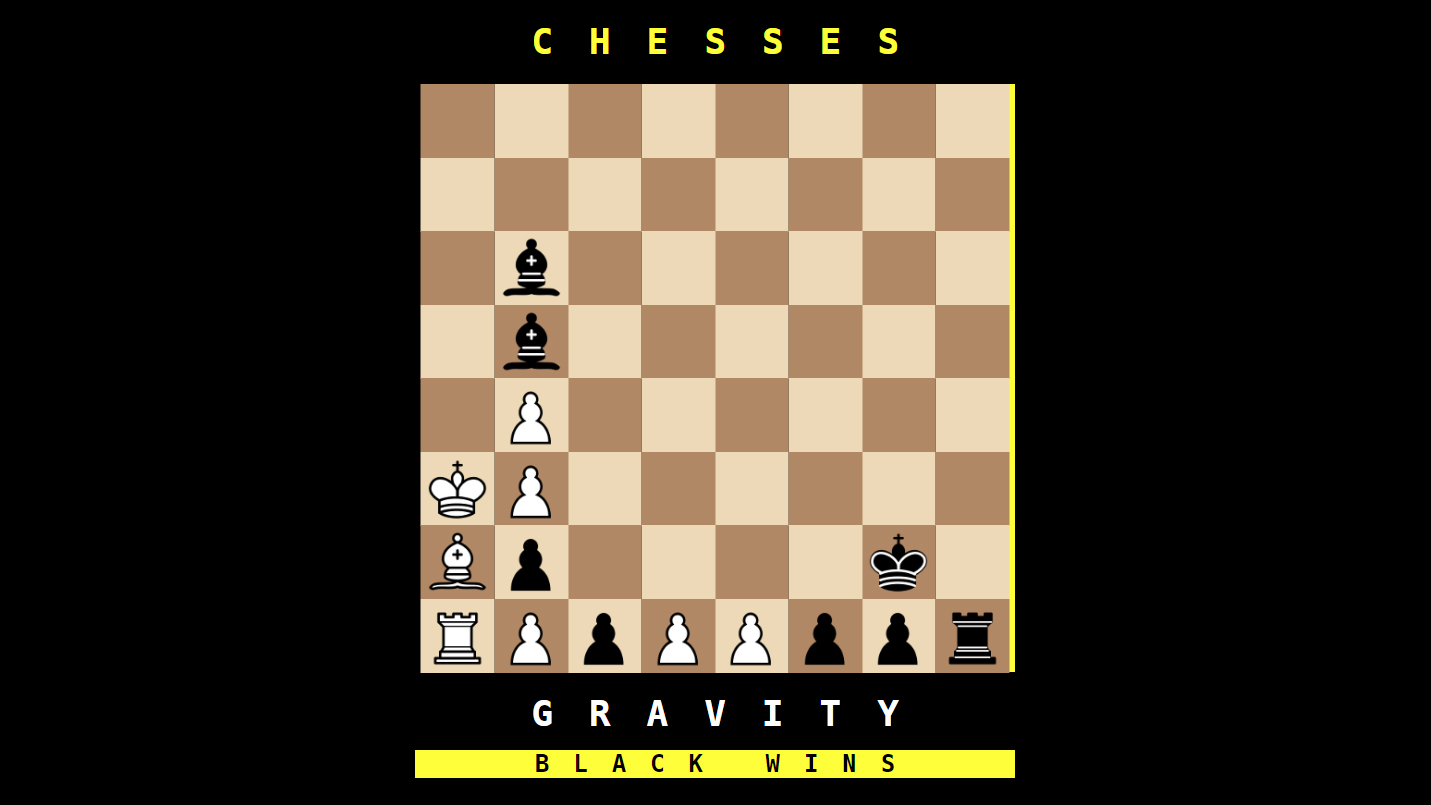

At the end of a game of Gravity, it often becomes impossible to stack pieces high enough to cross enemy lines. Eventually you're left with a row of surviving pawns that can't get past each other, and a draw.

Attacking the king is not easy. Say the space above the enemy king is protected by one of your bishops, and then you stick a rook on the king's head. It looks like checkmate, but it isn't, because the king can 'leap' up, take the rook, and then fall back down to its original position. It is briefly in the bishop's line-of-fire, but the rules only take into account where a piece is going to end up once a turn has fully resolved.

All of the games I've played have ended in draws except one, where I checkmated white (which was also me). The key is to lock down a stack of white's pawns as early as possible to limit their options, and then attack on the ground. But it's easy to defend, and I had to make some big mistakes as white to accomplish it.

There are only a few possible openings in Gravity. Most games begin like this: White moves any pawn one or two spaces, freeing their top rook to move across the board. Black now has two options. They can protect their rook by moving a knight, or move a pawn and allow white to take their rook. Whatever happens, white gets the opportunity to attack the top of black's ranks with its rook.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Black seems to be at a huge disadvantage, but if black focuses on forcing a draw, it isn't too tough.

What I like about Gravity is that, rather than just adding complexity to chess, it expresses some common feelings about the game. It evokes the debate over whether or not the white side has an advantage, as well as the concern that chess is becoming a game of draws due to how deeply it's been studied. It's literally being 'weighed down' by computer analysis here.

But that wasn't Barr's goal with Chesses or Gravity—or, at least, it wasn't the direct goal, which was to get people thinking about game design while documenting the game's creation. On the surface, Gravity is a visual joke: the gravity only makes sense if we imagine that the diagram is a vertical space, rather than a 2D representation of a board which would sit flat on a table.

"Years back I was excited (for reasons that elude me) about the fact Unicode has chess characters and I was making tweets with weird chess 'positions' and so on," Barr told me in an email. "That led me to tweets that had the standard chess set positioned 'sideways' because it was easier to represent that way. And that in turn immediately made me see the idea of the pieces falling to the bottom. Gravity chess."

Barr is an assistant professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts at Montréal's Concordia University and holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from Victoria University of Wellington. He's also the associate director of Technoculture, Art and Game, an "interdisciplinary centre for research/creation in game studies and design, digital culture and interactive art."

Creating games like Chesses is, in part, a research and education project for Barr. He documents his design process as a way to "demystify" it, he says, and to show that game design isn't about "intuition and magic" but hard work and lots of mistakes.

"Beyond that idea of revealing design itself, I think the games I make are hugely about a kind of 'research' for the players themselves," wrote Barr. "I like the idea that they provide an opportunity for players to speculate about games and design, how it works, how it could be different."

Not all of Barr's browser games are takes on Chess, though it is a running theme in his work. Among others, he's also made a mashup of chess and Rogue called Chogue.

"I think I like playing around with [chess] as a game designer/developer because it's kind of the quintessential game in some ways? It's just so game-y," Barr told me. "It's simple, deep, iconic. I've always been interested in taking some very basic game structure (like Pong or Breakout or Snake) and using that as the basis to explore game design by making modifications and seeing what happens."

You can play any of Barr's games over on his website (I really like 'It is as if you were doing work').

I'm a casual chess player, so while it feels like I've exhausted Gravity's potential at this point, it's entirely possible I've missed a better strategy. If you discover any interesting outcomes, I'd love to see them.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.