The making of Quake 2

Tim Willits explains how the classic id shooter came to be.

This article was originally published in issue 184 of Retro Gamer. Subscribe here for more features like this every month.

Few western developers had higher profiles during the '90s than id Software cofounder John Romero, and fewer still had a rockstar image to go with their fame. But after helping id to make the FPS mainstream with instant classics such as Wolfenstein 3D, Doom and Quake, John parted ways with the small firm, and its remaining developers made the decision to take their next project in a new direction, as Quake II level designer Tim Willits remembers.

“Romero was let go, and we took a different approach to the next Quake game,” he tells us. “Kevin Cloud stepped up to lead the project and refocus us on something that was more story-based and set in a different universe. Kevin had this great idea where he said: ‘Guns Of Navarone.’ That was the inspiration for Quake II, and it made sense because in the movie the Allies had to knock out the big guns that the Germans had before they could assault. So in Quake II, your job would be to knock out the big guns before the big dropships could come in. That’s why you were by yourself, because the human forces had sent individual pods out since everything else was too big and would get hit by the big guns.”

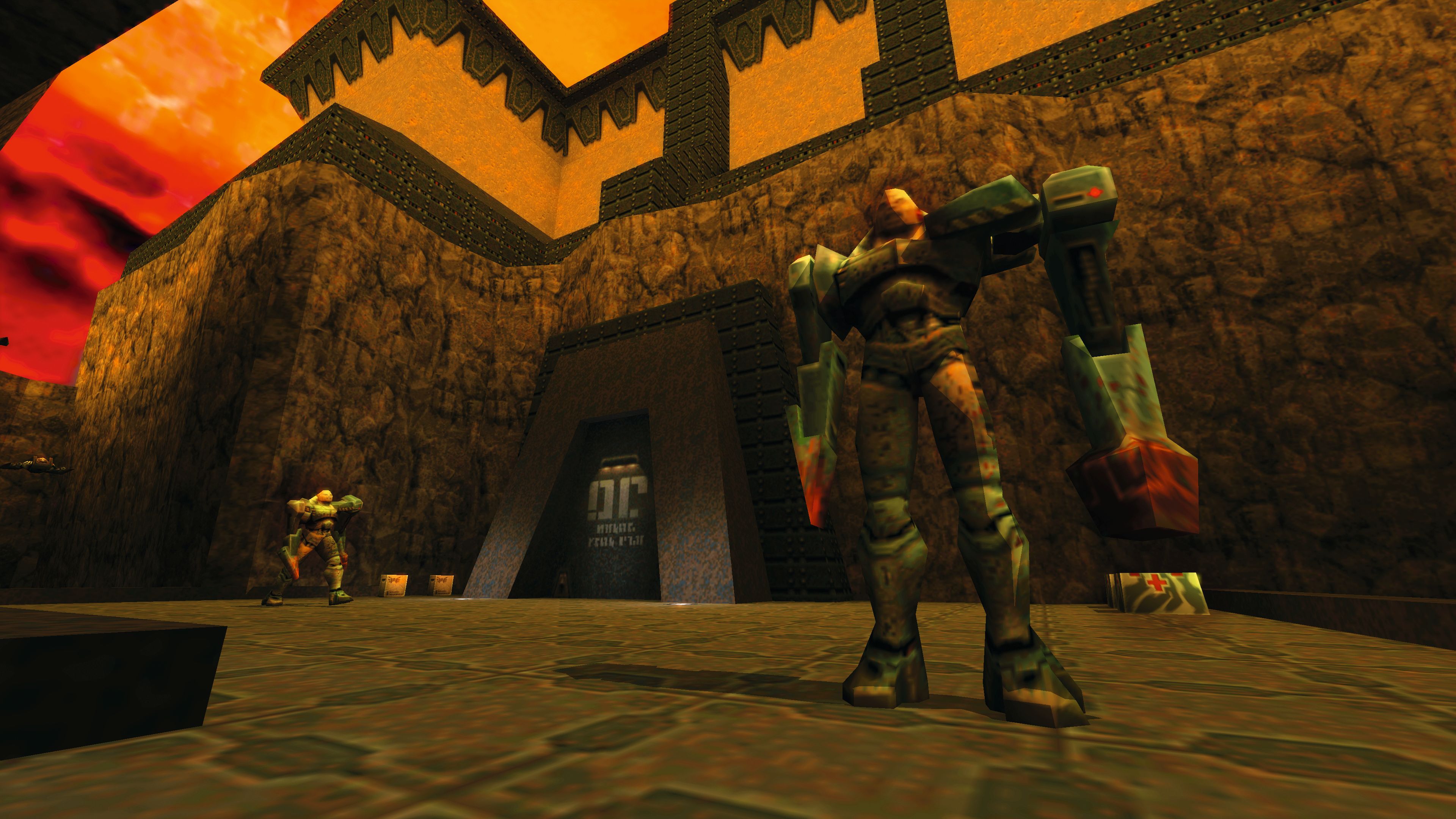

Of course, since id’s latest project was taking its lead from the Guns Of Navarone it would need an army as dark as the movie’s Nazi antagonists, which Quake II artist Kevin Cloud delivered in the form of a race of macabre aliens called the Strogg. “With the Strogg, Kevin wanted to create an enemy force that was unified but terrifying,” Tim explains. “So the Strogg were part-alien, part-vampire; they weren’t like vampires, but they were vampiric. Like the Borg [in Star Trek], their plan was that they would take over planets, and then use body parts—living tissue and organs—in reconstructing themselves and keeping themselves alive. Because they attacked different planets with different creatures, each Strogg was different, but the Strogg were also very unified because they were all part of a Strogg collective.”

But as horrific as Kevin’s vision for the Strogg was, the nightmarish aliens’ sci-fi backstory was clearly at odds with the Gothic horror narrative of id’s previous Quake title, which as Tim points out makes sense since Quake’s follow-up almost became a standalone project that would likely have kickstarted an entirely new id franchise. “We wanted to do something different with the next game, and we did consider not calling it Quake II,” Tim muses. “One of the names Paul Steed came up with, which I always really liked, was ‘Wor,’ but it was hard coming up with a name that everyone liked, so we just stuck a ‘II’ on the end of Quake. But it did hold true to that Quake DNA, where it was hardcore: there were big beefy weapons, there was over-the-top action and you were the hero saving the world.”

But while id strived to instil Quake II with the key tenants of Quake’s core gameplay, rather than reworking the sequel as a dark fantasy it decided to retain the project’s decidedly sci-fi -themed narrative. “We were a bunch of sci-fi nuts!” Tim reasons. “And it was refreshing for us to do something new but kind of familiar. With a sci-fi universe there was the opportunity to have super-cool weapons and we could have new types of creatures, so it really gave a nice palette to create a wonderful game.”

As well as favouring an alternate genre, Quake II would also differ from its predecessor by having a cohesive backstory, which instructed and informed the design of the project’s full-motion video introduction and the look and animation of its biomechanical alien opponents. “Quake was kind of a mess,” Tim concedes, “although it was awesome. But the Quake II team rallied behind one art style, one art direction and story. We had better design, and we were focused. Paul Steed came up with our cinematic intro, which was really cool. He had worked on the Wing Commander series, and so he brought experience of story-based sci-fi action games. Adrian Carmack did amazing concept work on the Strogg creatures, and then Paul added personality to the animations.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The follow-up to Quake was further differentiated from the original game thanks to enhancements that id’s lead coder John Carmack made to his Quake engine that allowed it to render brighter and far more colourful-looking levels. “We had a supercomputer that was literally the size of a refrigerator to process the lighting for the maps—it was so cool!“ Tim enthuses. “No game had had coloured lighting before Quake II. So we were like kids with new toys; we went all crazy. I know there are some levels that look a little oddly-coloured, but it did give it a more colourful look. At the time it was like: ‘This is awesome! Green and blue lights!’ We also had light bouncing—simulated radiosity—so every corner of the world had some lighting.”

Beyond aesthetics, the stages in Quake II also stood out from their Quake equivalents thanks to their more wide open and less linear nature, which Tim puts down to accumulated knowledge, a story-led approach to level design and the knowledge that PC gamers were continually upgrading their PCs with the latest tech. “We had more experience making levels, and we were trying to tell more of a story. Like there was the jail, there was the hanger and the processing facility, so we tried to give more identifiable locations to the areas. Plus computers were running faster. It was just a combination of all that, really.”

The railgun in Quake II was inspired by Eraser—the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie.

Tim Willits

Additionally, Quake II’s levels would be mission-based, and unlike Quake its sequel would require players to make use of innovative ‘hub’ areas to jump from one stage to another and back again. “I can’t remember if it was something that we had consciously planned for or if it just evolved,” Tim ponders, “but you had these missions, and you would get radio alerts, because we just wanted to tell a better story and give a better experience, and the hubs were a byproduct of that. The hubs made the environments richer, so the world felt like a real place that you were infiltrating. They gave us the freedom to reuse areas and make players feel like they were in real space.”

One innovation that proved a step too far, however, was the option of rescuing traumatised marines being loaded into meat processing machines in one of Quake II’s more gruesome missions, the processing plant. “We had that one mission with the processing plant,” Tim recalls, “and you could just turn off the machines. I think it was the limits of the gameplay scripting, where what do you do with the marines when they’re out? We didn’t have AI, so they wouldn’t follow you around. Plus those poor souls, they were already damaged beyond repair from the Strogg experiments.”

Aside from making decisions on level design mechanics, new weapons were being designed for Quake II, although these were complemented by a selection of existing designs made popular by earlier id FPS. “There were some tried-and-true weapons—the lightning gun and the rocket launcher were from Quake,” Tim acknowledges, “plus we had machine guns and the BFG from Doom, but Quake II was sci-fi, so we also had hyper blasters. We tried to make the new Quake II weapons exciting and interesting, but yet remember that they always fulfilled a purpose in a situation. At id, we’ve always believed in situational weapons. So if a guy is close-up you use a shotgun, if a guy’s far away you use your machine gun. You’ve got projectiles, explosives to get that instant hit. Each of these weapons actually fits a purpose of the gameplay. So we would find a situation that we wanted to engage an additional weapon for and then come up with a weapon.”

Arguably the most memorable of the weapons to make its debut in Quake II was the now-legendary railgun, which Tim credits to company research on arguably the most memorable big-screen action hero of the '90s. “The railgun in Quake II was inspired by Eraser—the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie,” Tim reveals. “I went to see it with the guys, and the next day I went to John Cash. I told John: ‘It’s like a rocket, but it’s an instant hit—it’s called a railgun!’”

Perhaps reasonably, given the destructive power of Quake II’s railgun—not to mention its other deadly armaments—the game’s sole animator Paul Steed decided that the focus of these lethal weapons, the Strogg, should be dangerous even in their death throes. “Paul wanted to bring more personality to the creatures,” Tim recollects, “so the marines could shoot their heads off, but they could still shoot back before they died. He thought it added more meat to the gameplay, so he drove that thought and inspired us to do that. Paul was our only animator, and he did model, too, so you could see his personality in some of the characters in Quake II.”