The future of Kerbal Space Program under Take-Two's ownership

Squad has already been to the Mun and back—how can Private Division take it higher?

If there’s any tale as long and dramatic as that of the space programs, it’s the story of their funding. The budget of NASA has its own Wikipedia page, such is its capacity to stir strong feelings about our priorities as a species—not to mention impassioned speeches from Neil deGrasse Tyson.

The funding of Kerbal Space Program, too, has its own story. You might imagine that lead developer Felipe Falanghe left the marketing company he worked at to start work on his rocket simulator. And it might have happened that way, had his employer accepted his resignation, rather than suggesting he make the game for them instead. Yep: Kerbal studio Squad was that marketing company—for a long time balancing the development of a hardcore engineering sim with the construction of high-tech advertising installations for clients like Coca Cola.

It’s an unlikely origin story. But then again, it’s hard to imagine a likely path to Kerbal’s success. This was a literal pipedream, a game about firing volatile tubes of explosives into the sky, the way Falanghe did with modified fireworks growing up. But it caught the popular imagination, and Kerbal became a beloved fixture of PC gaming—joining Euro Truck Simulator and Arma in powering simulation out of its niche and into the mainstream.

The phenomenon was such that, when Take-Two announced its acquisition of Kerbal two years ago, the news wasn’t particularly surprising—even if Squad had released a statement clarifying that it "continue[d] to be an independent studio" just a week before. Like NASA in the ‘60s, the game had become a major economic concern in less than a decade—more than significant enough to justify the attention of a publisher that owns Rockstar Games.

At the time, with a flag already planted in 1.0, Squad was hard at work planning its next landing, an expansion dedicated to recreating famous missions. "Take-Two were very useful," Squad lead producer Nestor Gomez remembers. "They provided a lot of feedback on the release for Making History."

A few months after the acquisition, Kerbal was officially folded into Take-Two’s new label dedicated to mid-sized projects, Private Division. That’s a name you’ll have started to see crop up more frequently since, alongside Obsidian’s The Outer Worlds, and Patrice Désilets’ belated follow-up to Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood, Ancestors. These are projects with ambitious scopes beyond the financial means of indie publishers like Devolver or Versus Evil, and yet not large enough to become flagship titles like Call of Duty or Far Cry—in other words, the games that had previously fallen between the cracks for Take-Two.

It’s about making what you can already do in the game a lot better

Nestor Gomez, lead producer

Michael Cook, a "player and admirer" of Kerbal who joined Private Division to become the game’s executive producer, believes there’s no connecting factor between the label’s games beyond quality.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"We want to collaborate with premier developers who are working on great things," he says. That’s essentially what we’re doing with Kerbal and Squad—just working with great people with great ideas."

That said, the common link between the other announced games on Private Division’s roster is that they come from developers with prior experience in mega-franchises—Fallout, Diablo, and Battlefield. In that sense, Kerbal is still the outlier—a Mexican marketing company’s first foray into software that rocketed unexpectedly upwards. And Squad still operates in its own way.

"I would say that, for the most part, we’ve been able to continue in the same direction as before," Gomez says. "We are pretty much free to organise ourselves, and we have a lot of creative freedom. In those terms, not much has changed. But on the other side, we now have better support with Private Division behind us."

Squad’s independence has not always seemed like a blessing. In the years after Kerbal exploded, the studio’s bizarre omni-directional approach continued as its co-founders wrote a film script and started a record label. There were rumours of crunch and unpredictable firings.

"Squad was a small team that grew up very quickly," Gomez reflects. "There were some challenges managing that growth. I wasn’t there, so there’s not much I can say about that. But since I joined, and before Private Division came in, there was always the intention to get better at things. And we keep doing that so far. Right now, those kinds of things are not happening anymore. We’re trying to get better at having people happy in the team."

Cook says that Gomez is being humble. "The team loves Nestor," he says. "Every time I visit it’s great to see the way the team functions together. He’s done a great job building a culture there since he’s joined."

The small group that makes Kerbal has changed over the years. Some early staff now work at Valve, while the game’s originator, Falanghe, left in 2016. His statement at the time suggested that—to put it in the terms of physicists—where once the game was a liquid he was responsible for guiding, it was now a solid. He could turn his back on it without fear that it would lose its shape, knowing that the balance between its unique playfulness and hard sim core would be maintained. The sense of relief was palpable.

"It means that conceptually, the game is complete," he said.

It was a relief for fans, too, to know that the ship could be steered without its commander. But you have to ask whether a conceptually complete game should continue development. What rocks are there left for Squad to colonise?

"For me, it’s giving players a better tool to do what they want to do," Gomez says. "That’s driving me every day."

In Kerbal’s December update, Squad gave the gift of Delta-v read-outs. That might sound like frighteningly high level flight dynamics, and it is, but if you can get your head around those values you can measure the impulse needed to perform a landing manoeuvre long before you attempt it. It could mean the difference between a stranded Kerbal or a triumphant journey home.

Just last month, a new manoeuvre mode exposed yet more information to players—with the aim of smoothing interplanetary transfers. Post-Falanghe Kerbal appears to have found purpose in making the deepest parts of its simulation visible, and accessible with pliers. "It’s about making what you can already do in the game a lot better," Gomez says. "We’re focusing on that."

Breaking Ground

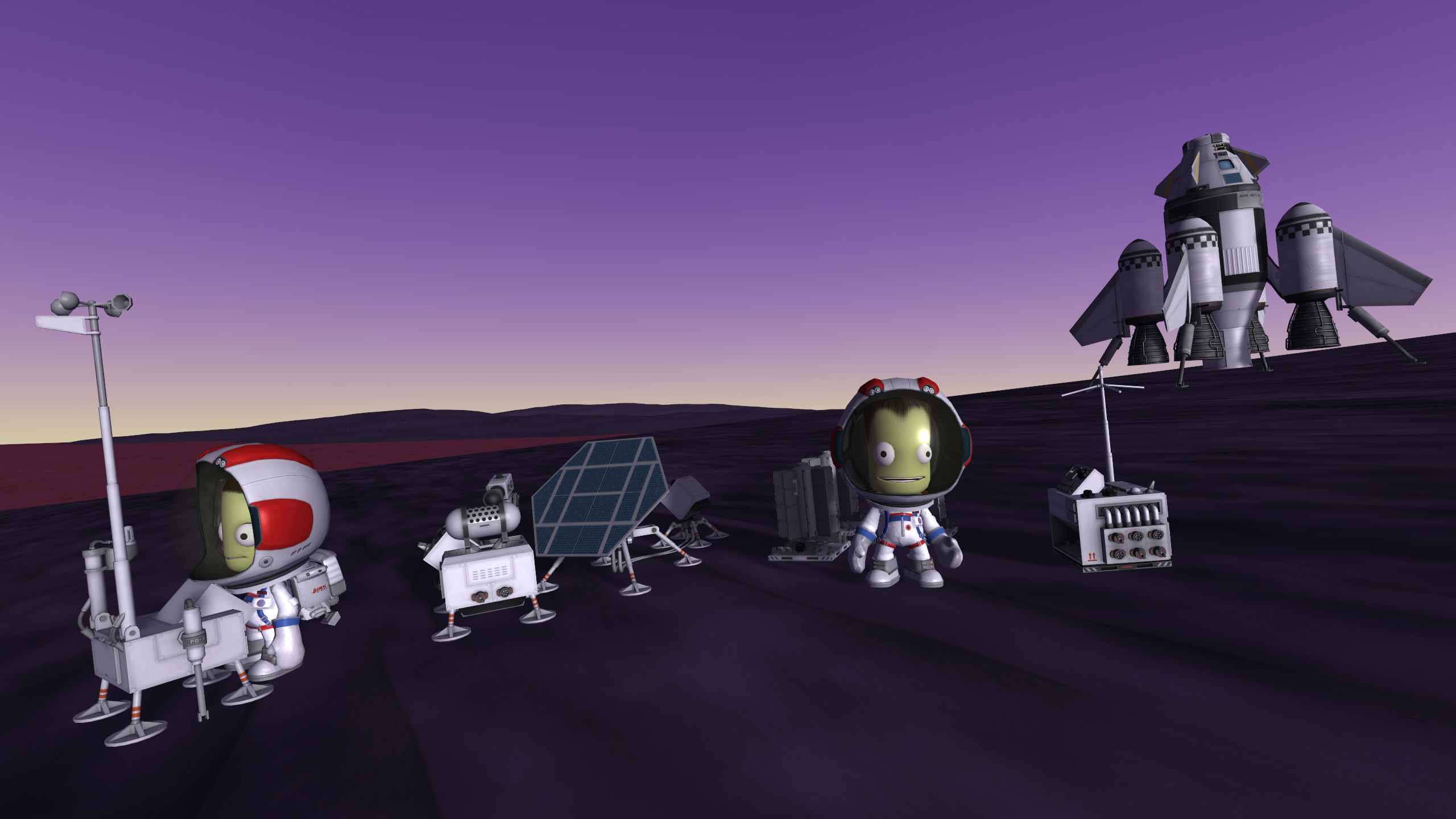

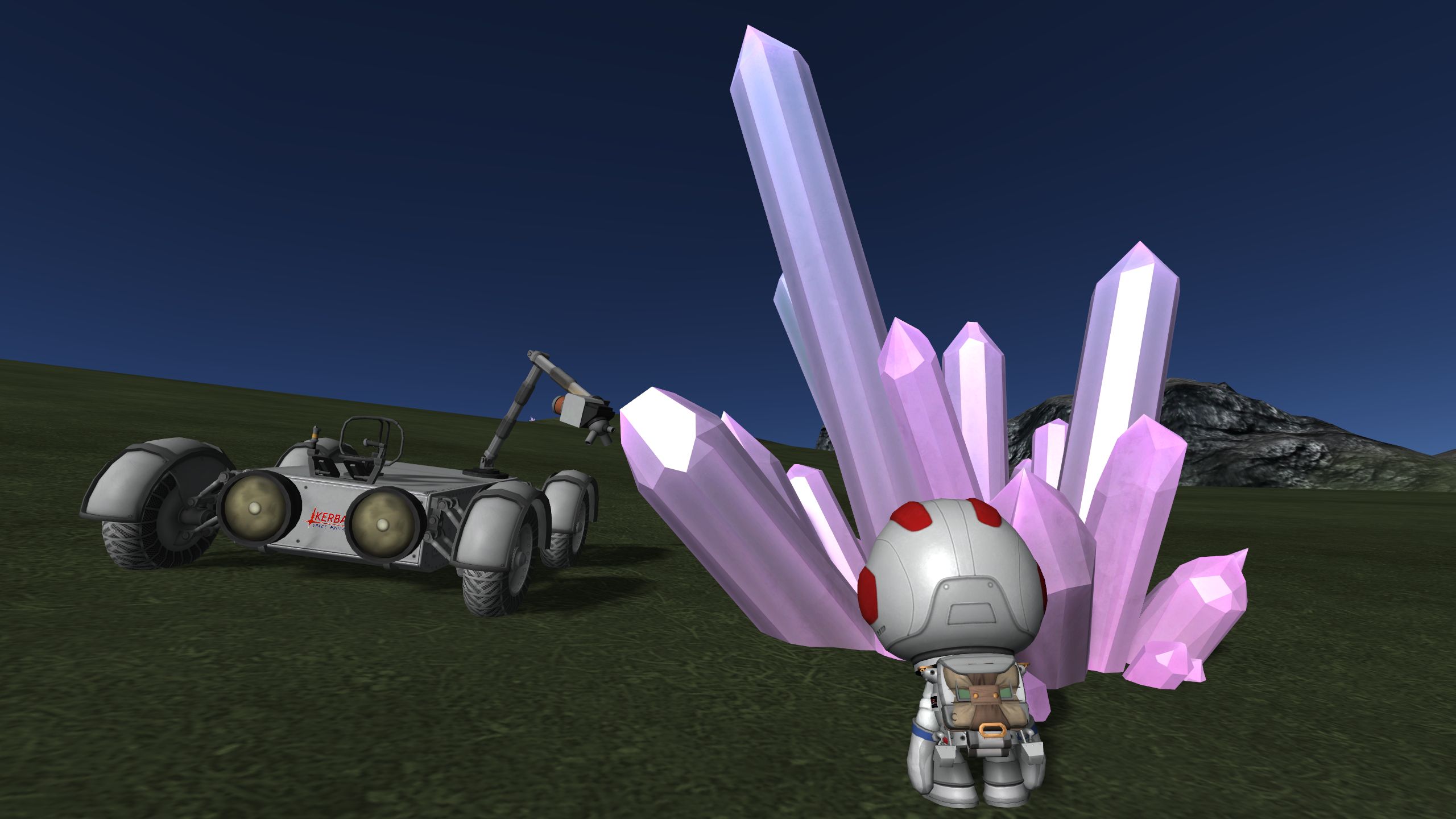

That goal has led to more than mere tweaks. Kerbal’s second ever expansion, May 30’s Breaking Ground, is so called because it’s about cracking open the surface of planets—giving the destinations of your missions a little extra depth. Once landed, you’ll be hopping in your rover to search for different elements, buried in rocks and volcanoes, to "do science with them". In the parts of the landscape you’re not digging into, you can perform experiments loosely based on those NASA conducted during the Apollo missions, deploying weather stations and—here’s where the loosely comes in—tools to detect impacts.

"You will have to impact something into the ground to get some readings, so we expect people to have a little fun with that one," Gomez says. "We always want to keep the humour of the Kerbals."

In fact, much of the new expansion is designed to aim the camera at the game’s goofy stars, to give you more reasons to take silly screenshots in celebration of your achievements. But, knowing the Kerbal community, fans will be more excited to share bold contraptions made possible by the new robotic parts coming in Breaking Ground.

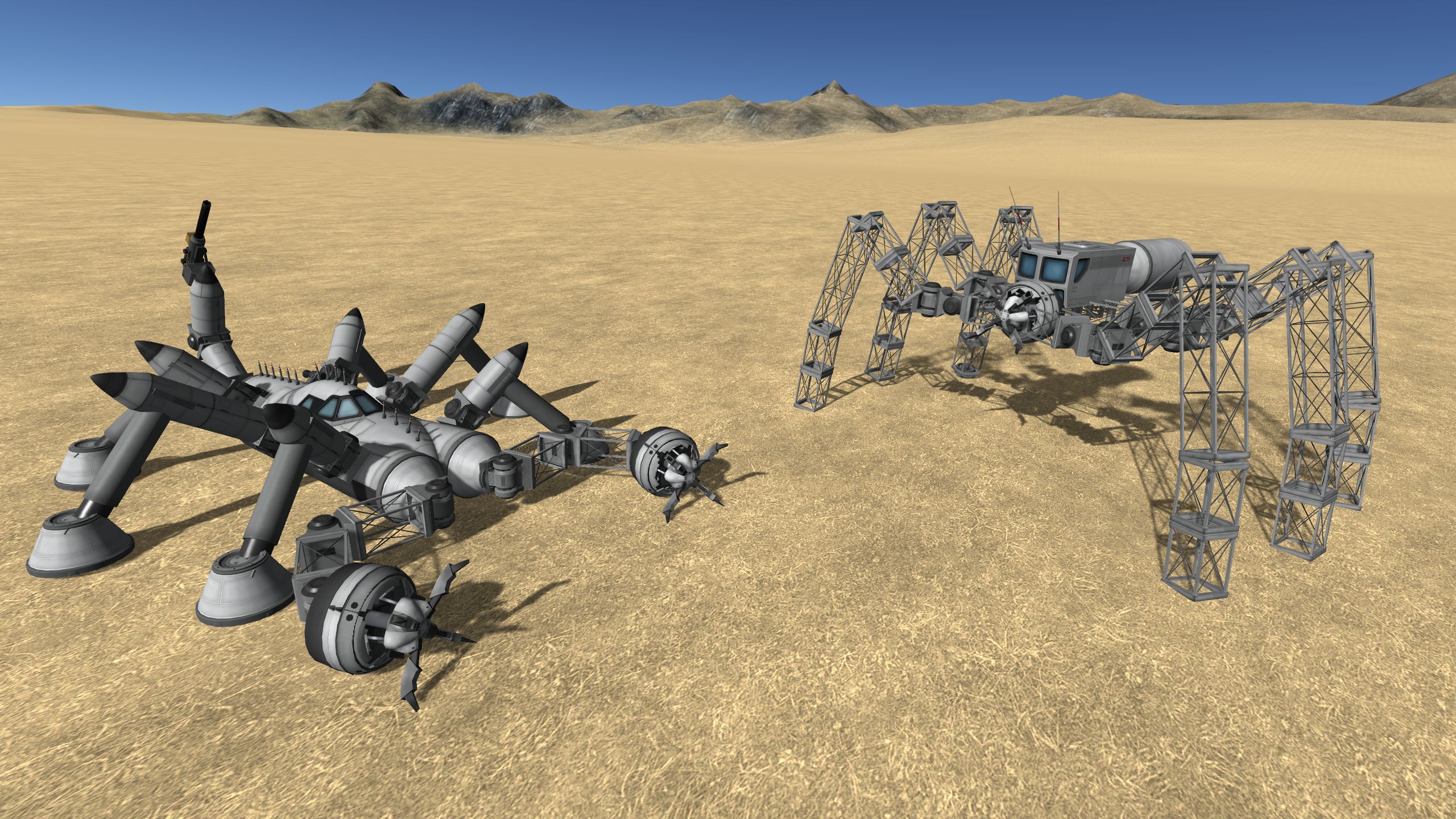

"They’ll allow players more control over their constructions," Gomez says. You might want to rotate your engines for vertical take-off or, more ambitiously, create robotic arms for use in docking. Squad expects players to exploit the new tools for quality-of-life improvements, too—a deployed rover currently tends to go the same way as a dropped piece of buttered toast, but a specialised device could keep the vehicles upright. Like all of Kerbal’s best tools, the new robotics are intended to work as an open-ended system.

"We are always listening and looking at what people are building, and most of the time we get inspiration from them," Gomez says. "People already use the existing parts, or other parts created by modders, to build super interesting things like mechanical spiders."

At the time of Making History, Squad was criticised for being deaf to its modders, centering the expansion around classic real-world craft that the community had long since tackled itself. Gomez acknowledges that it’s tricky, sometimes, for the team to know where to focus its efforts. But he’s confident in the feature set of Breaking Ground, and I think he’s right to be. It’s an expansion focused on what comes after—after landing, after players have exhausted all the pre-built equipment available to them—rather than what came before. For all its open admiration for vintage NASA and the cosmonauts, that’s what keeps Kerbal exciting: the allure of new possibilities. That’s what attracted Private Division, after all.

"We definitely see a strong future to the franchise and have lots of things planned," Cook says. "It’s great to see something that’s been so popular for so long, and I hope that with Private Division as part of the equation, we can introduce it to people who haven’t been reached yet, and support Squad to be able to do bigger and better things."

As ever, Squad is looking upward—but also forward. Devotion to space history only makes so much sense when your pilots are gawping green mascots, anyway. "NASA never did an experiment to crash something," Gomez admits. "But it’s a perfect example of having fun with science, no?"

Update and correction: Squad would like us to point out that NASA did do an experiment to crash something. Read more here.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.