Firewatch has a genre problem

Spoiler alert! This article presumes you've finished Firewatch, and directly references events from the end of the game.

I love a lot of what Firewatch offers. Its environments, soundtrack, dialogue and animations are all superb. The game gets so much right that I can't help but be disappointed by its overarching plot—specifically the middle-act, when Henry suspects his conversations are being monitored and his paranoia starts to build. It's a sequence that does nothing to rein in our own expectations as players, resulting in a genre fake-out that I feel undercuts the final resolution.

In fiction, there's no guarantee what you're experiencing will follow our world's rules. To an extent, genre mitigates the uncertainty. If all you knew about a fantasy novel was its genre, you'd still be armed with some basic context. A conversation about religion might have particular significance, because gods can be a real and active participant in events. In a sci-fi film, the same conversation would mean something different. Or not, because, from that initial assumption, the creator gets to define their own rules—to confirm, withhold, subvert.

In games, these boundaries feel fuzzier, because our genre labels aren't defined by the story being told. 'Strategy,' tells you nothing of the world. 'FPS,' isn't an indicator of period or tone. 'Action,' says nothing about anything. That rarely matters in games, because plot is so rarely more important than design. A setting can be a big part of a game's appeal, but the systems that live within it are often more so.

For first-person adventure games—or walking simulators, if you must—plot, setting and narrative genre come to the fore. And walking simulators love to defy expectation.

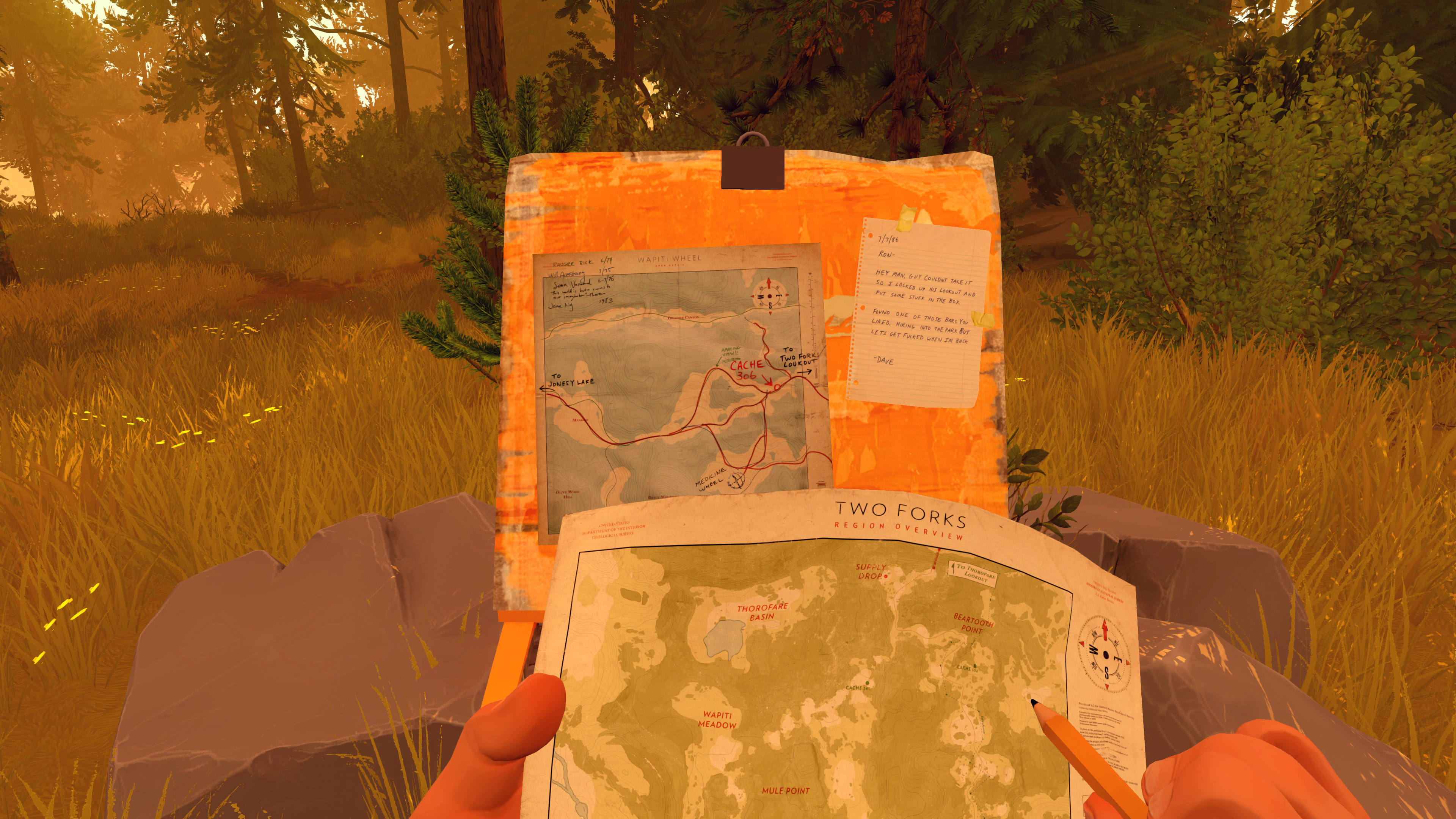

Firewatch is drama in a thriller's clothing. As Henry and Delilah's paranoia builds, it tips the scale of realism. At its peak, the pair think they're part of some strange monitoring experiment—a Lost-esque zoo in which they're the primary attraction. Players are left unsure if this is the sort of thing that could happen in this world. Is it believable that an unknown research company would move to the wilderness to start monitoring conversations? It's certainly not outside the realm of possibility because, until the rules of the world are established—the extent to which it operates in parallel with our world—nothing is outside the realm of possibility.

The paranoia only works because the plot and tone mimic the style of a thriller, creating a tension that doesn't actually exist. Henry and Delilah's growing fear and panic resonate, because they are isolated, lonely and, above all, well written characters. But, viewed through the filter of the real world, it's clear they're being ridiculous. When it's finally revealed that, yes, it was ridiculous—that the reality was far more grounded and tragic—there's a sense that the player has been played. Aha! Thought this was a mystery, did you? It was heartfelt drama all along!

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

This could have been an effective and memorable trick. Just look at Gone Home, which, in my view, blurs its tone more deftly. It looks like a horror game, because horror is a genre that revels in taking nice, safe environments and subverting them. Of course an old, empty house feels scary—any old, empty house does. Within that setting, the personal dramas unfold—the potential for horror hovering at the edges. It's not a ghost story, but, absent of other characters, it feels haunted by past events. The transition to normality feels smoother and more deliberate.

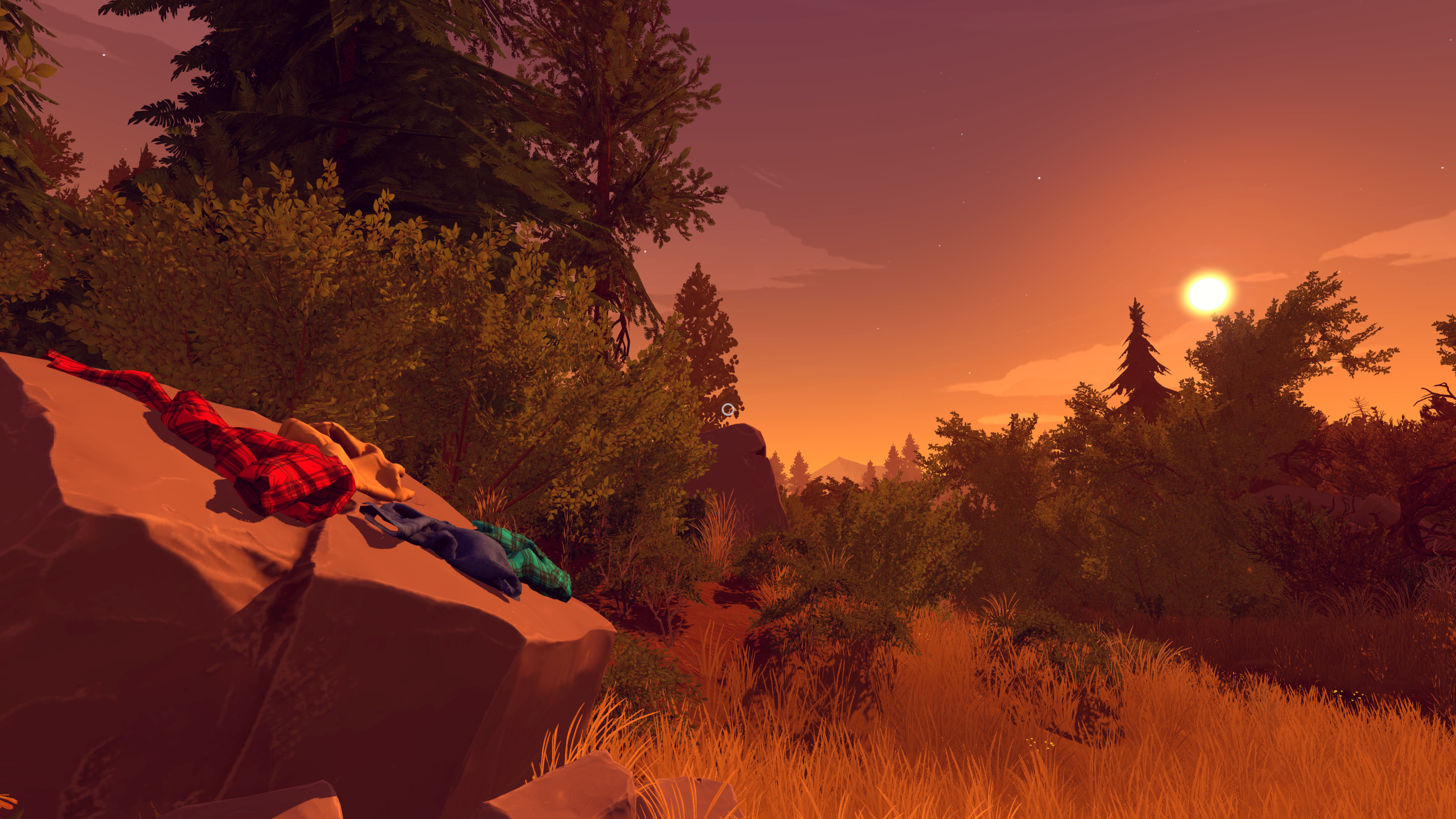

In Firewatch, it feels more jarring. The paranoia feels like a strange tangent—some second act padding to stoke intrigue on the way to the finale. It's the setup for an ending that doesn't exist. I actually like Firewatch's ending, but I think it would work better attached to a more subdued game—one that allowed the drama to come through realism. The discovery of Brian's body should be the gut punch that sets up Delilah's decision to leave, and Henry's muted semi-resolution that life is sad, hard, complex and ultimately inescapable. For me, the moment fell flat. I was too busy readjusting my expectations. I didn't feel the tragedy in front of me, because the reveal took me out of the story. I should have been reacting to the plot, but I was reacting to the shift in genre. "Oh, it's not this, it's this."

From the reaction I've seen to Firewatch, some players equally felt that the return from thriller to drama was itself a disappointment. They wanted the thriller to continue—to itself pay off in a more satisfying way. It's tempting—in all forms of media—to see drama as more worthy, but I've never been convinced by that view. I understand the disappointment that there wasn't a crazy research experiment to uncover. That sounds like a fun, intriguing story in its own right.

The existing resolution doesn't work from either side of the genre divide, because the central motivation—Ned's desire to keep Henry away from Brian's body—doesn't lend itself to faking a creepy monitoring station. It doesn't feel like a believable reaction, on an rational or emotional level. Maybe four hours of interpersonal drama wouldn't have been interesting enough. Maybe four hours of schlocky thriller wouldn't have allowed for the same poignant character detail. Instead, though, we get a tonal dissonance that feels aggravating in both directions—and disappointing in the face of the many things Firewatch does well.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.