'Edutainment’ games have a reputation for compromising heavily on the ‘-tainment’ by substituting fun for thinly veiled school lessons. While classics like Carmen Sandiego are remembered well, the ’90s brought a slew of kids’ games with a different spin: instead of being centred around classroom curriculums, these aimed to teach ways to think and learn, introducing previously unseen challenges to design and development. Two significant examples are Humongous Entertainment’s point-and-click adventure titles, and later, the slew of Lego-themed games spanning multiple genres. Co-founded by Ron Gilbert (of Monkey Island fame), Humongous had a number of series targeted at varying age ranges, including Putt-Putt, Freddi Fish, and Spy Fox. Lego Island, an open-world sandbox game, strived to offer a brick-based smorgasbord of activities in a fully-3D environment. Though its box boasted about characters, vehicles and pizzas, the developers worked to ensure it also carried educational value.

Each of Lego Island’s playable characters encouraged different kinds of thought. Policeman Nick Brick’s activities focused around critical thinking and investigation, while pizzeria owner Papa Brickolini’s juggling and dancing encouraged more kinesthetic learning and interaction. “At school, there were some people, like myself, who were really bored when it was just presented verbally,” says Wes Jenkins, Lego Island’s creative director. “I learn better visually.” That freedom to explore new ways of learning was virtually unseen in other titles and remains rare in kids’ games today.

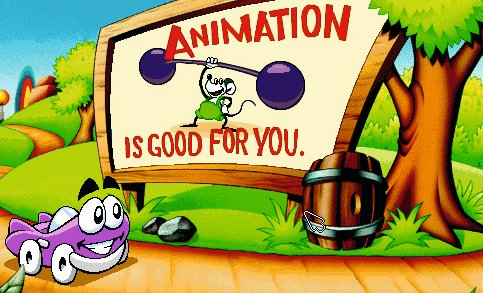

Developers had to strike a careful balance when being mindful of their audience. Complex words and sentences could confuse kids and some would only have a loose grasp of the language. However, watering the game down might make it more accessible to very young children, but would alienate anyone else. Humongous’s solution involved substantial interactivity. In each area, almost every rock, cloud and flower was clickable, eliciting a cute animation or a quip from the characters. “You could explore the game for hours without knowing what the narrative was,” says Mike Paganini, who worked as a designer and art lead at Humongous Entertainment. These bite-sized morsels took considerable time and effort, but they allowed players to simply enjoy poking and prodding the world.

While Humongous adapted the well-established point-and-click adventure genre to fit its audience, Lego Island was built from the ground up for kids. It presented an environment to explore and interact with instead of a directed experience. “You could just stand in one place and all kinds of different characters would come up to you,” says Jenkins. “If you just want to walk around, if you just want to stand there, or if you want to play games… We just wanted to make it a Lego world.” From building a car and racing, to simply walking about and listening to the islanders chatter, the game catered to various levels of depth. Combined with multiple methods of interaction via the playable characters, Lego Island was able to appeal to a wide range of children, across age, gender, and personality.

“It was a labour of love,” Paganini says. “Everybody cared about the product, everybody was interested in what other people were doing. It wasn’t uncommon for someone you didn’t know to walk up behind you and say, ‘Hey, what’re you working on?’ and be genuinely interested.”

Due to the infancy of the genre, Humongous had the leeway to experiment. Although point-and-click adventures were common, there were few, if any, targeted at young children. That freedom, combined with the passions of the developers, invigorated the team. “As a game developer, that may have been the golden age,” Paganini says.

Unfortunately, it couldn’t last. The number of platforms increased dramatically. The scale also outstripped what young players typically receive now. “To me, the analogy is that Humongous was making motion pictures, and children’s games today are TV shows. You try to extend the brand by making more and more television shows, versus really investing in something that someone is willing to play for 10, 12, 20 hours,” Paganini says. Maintaining the high density of click points and extra tidbits over a feature-length plotline wasn’t simple. “I think the life expectancy of a children’s game now is more around two or three hours. The math doesn’t add up.” These days, with the ubiquity of mobile devices, the simplicity of app stores, and the refinement casual games have undergone, there’s much less room for exploration. While Humongous wasn’t able to adapt, Lego produced a wide array of titles and eventually branched out into lighthearted tie-ins to popular franchises such as Batman and Lord of the Rings.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

That’s not to say kids don’t have options for titles that subtly teach. There are more options than ever for mentally productive games—they’re just not made exclusively for kids. Minecraft was made for all audiences, but it’s become hugely popular with young gamers and even found use as an educational tool. Although those games were mostly products of a budding industry and innovative developers, kids have more to play than ever—and more ways to learn.