Deleting clutter: why we like games about cleaning up messes

Why is tidying so satisfying?

I recently spent an hour clicking on pictures of rocks and logs to make them disappear. I was cleaning up my farm in Stardew Valley, but that friendly little narrative aside, I was really just clicking on things to delete them. And I was happy to do it. Toiling in the fields with my click-axe, pulverizing rocks, cutting down trees, and slicing up weeds is weirdly pleasant in the mindless way picking pills off a sweater can be. I wondered why, so I asked a psychologist.

Jamie Madigan, who holds a Ph.D in psychology and writes about the science’s intersection with games, tells me that the pleasantness of tidying may be related to the broader joy of finishing what we start. “There's a phenomenon called the Zeigarnik effect,” Madigan wrote, “where incomplete tasks create a mental tension that is released when we finish.”

Madigan also pointed out that studies—including Zeigarnik’s—have shown that we remember more about tasks which have been interrupted than those we’ve completed, presumably because we need to recall where we left off if we’re to return to the project. And that sense of ‘incompleteness’ weighs on us.

Leaving things unfinishe-

Zeigarnik found that participants who were interrupted in the middle of a task could be very unhappy about it. It’s easy to empathize. The experimenters timed interruptions to break the subjects’ concentration when they were most engrossed in the task, and I’m frustrated just by reading the example: “The subject is moulding the clay figure of a dog; he has reached the point where something four-legged and ‘dog-like’ is appearing, but there is still grave danger that his ‘dog’ will become a ‘cat’ before he is through.”

Incomplete tasks are also shown to have a lengthening effect on perceived time duration. In a 1992 study by Noah Schiffman and Suzanne Greist-Bousquet, participants were either given 10 or 20 anagrams to descramble. Those who were given 10 were allowed to complete the entire set, while those who were given 20 were interrupted after solving the first 10 (which were the same problems the other group was given). Both groups were then asked how long they’d spent solving the anagrams. The group that was interrupted felt more time had past.

Horrifying. It’s like the teacher saying “pencils down” while you’re halfway through writing a sentence. “In 1953, Samuel Beckett's famous play Waiting for-”. Just awful.

I surmise from all this that one of the reasons I clean is simply to get the clutter off my mind. To complete a task like tidying my farm, or some sub-goal in that effort, is to allow myself to forget about it—a relief even if the task itself is simple and repetitive.

The feeling applies broadly to games. For instance, I suffered the ‘one more turn’ effect of Civilization acutely last Sunday afternoon as I attempted to conquer Japan. I was forced to leave my conquest in an unfinished state, with only two of three cities captured, to take my puppy to training class. When I got home, even after an hour of failing to make a bark monster look at me, I could still recall my troop formations and thought about the scenario a few times until I got back to my desk to take care of Osaka. Likewise, visualizing a plan for my Stardew Valley farm and not being able to complete it is bothersome. Be it chopping down trees or forcefully annexing cities, what is started must be finished.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Cleaning up

But what about cleaning itself? Why, specifically, does clicking on rocks to make them disappear feel satisfying? That’s what I set out to discover, but my research on the subject of tidying was frustrating, turning up pop psychology stories about how to unburden your refrigerator door for a healthier life and 10 ways to find your Zen by reorganizing your closet. I can’t wait to create a bottle opener hierarchy to determine which deserves to stay in my kitchen drawer.

But maybe all the life hackers are onto something. Article after article says that clutter increases stress, and though I've had trouble finding a lot of hard evidence, it is accepted that we can only process so much visual information at a time. And yet many of us hold onto clutter despite the disarray impeding our focus. We tend to value things we own more just because we own them, making it hard to toss even trivial things. But what if I need it later?

A game, however, can lay that disarray into a grid—some squares pristine, others clearly marked as unsightly junk (which you've never really owned)—and all you have to do to restore order is click. Perhaps deleting virtual clutter is pleasant because it lets us enjoy tidying and organizing in a space cordoned off from our real belongings. We get to remove stressful visual noise without the stress of actually throwing out our decaying t-shirts or those bad oil paintings we did in college (using examples from my own life, here).

The Gestalt Principles

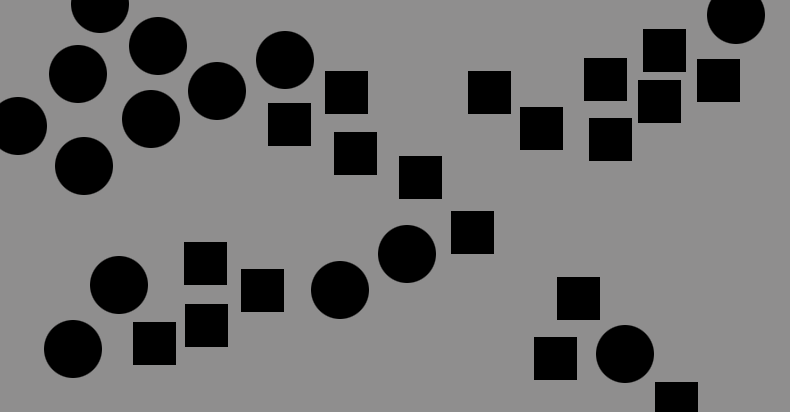

The composition on top is in disarray. Its elements can be grouped by similarity and proximity, but not in a very meaningful way. It's ugly. The figure on the bottom, while not rigidly gridded or spaced, is a more pleasing abstract composition, even though it uses the same elements. I suspect that if the ‘clutter’ in a game is arranged in a pretty way, it won't be as effective as it can be at motivating 'cleaning.'

From a visual design perspective, Gestalt psychology can also help explain our negative feelings toward clutter. The Gestalt laws of grouping are set of principles (observations, really, but useful ones) regarding how we perceive images and scenes, and are commonly applied to graphic design and fine arts.

According to the Gestalt school of thought, the 'whole' we perceive when looking at a scene is not just the sum of everything in the scene. We simplify. A cross is not four lines meeting at the center, for instance, but two lines intersecting each other. And when we look at a pile of potatoes, we don’t think about each individual potato’s relationship to all the other objects in the scene. We see the potatoes as a group, because they’re similar to each other and they’re next to each other, and then think about how that pile relates to other groups in the scene.

If all those potatoes are scattered around with intentional discord, we'll still group them, but the scene becomes unsightly and difficult to process. It's just bad composition. A still life painting in which all of the objects are roughly equidistant from each other would be a terrible still life painting by most accounts. Painters divide small objects into masses, creating pleasing designs through the relationships of large shapes, just as music composers don't treat notes as independent from each other, wildly banging on pianos (unless that composer is H. Jon Benjamin).

Apparently, we actually like cleaning quite a bit.

Ugly compositions like the Stardew Valley screen below stress me out. I want to rearrange it, to create some order—just a bit of decent landscaping. And I’ll happily do it if a game gives me the tools. I may even want to ‘fix’ the scene despite not being all that interested in the rest of the game—just by running Stardew Valley to take a screenshot of my cluttered farm I risked becoming absorbed by cleaning.

It all stacks up

The visual discomfort caused by chaotic scenes combined with the Zeigarnik effect, which prods us to complete tasks we start, may be what turns a quick Stardew session into an hours long rock smashing marathon. We’re attacking stressful disorder while observing clear progress toward a goal, motivation and reward neatly coiled together.

The act of removing junk and restoring order is present throughout videogames of all types. Tetris doles out satisfaction with the deletion of lines, open world Ubisoft games have us wipe the markers off maps, and Viscera Cleanup Detail takes it literally, having you clean up the gory mess left by other games. It’s not even that big of a conceptual leap to see how ticking down the number of Zeds in Killing Floor 2 is a more complex method for deleting rocks. Take a nice scene and fill it with turmoil, and we're compelled to clean it up. Apparently, we actually like cleaning quite a bit.

And yet there are three empty coffee mugs on my desk I haven’t touched in days—dang. Madigan suggests my lack of motivation in real life may be because the rewards of tidying aren’t as neatly packaged out here. “You get concise, specific feedback about what you do in games and you can usually see progress towards a goal and get larger tasks broken out into quickly achievable sub-goals,” he wrote. “Cleaning your house, getting a promotion, or getting fit don't offer that kind of feedback.”

So while there may be three coffee mugs on my desk, along with a twist tie, a piece of pizzle (which I recently discovered is the nice word for bull penis, something puppies love to chew), three USB drives, a crumpled plastic wrapper, a plate and fork, six pennies, two dimes, a quarter, sixteen small nails that got stuck to my speakers when I shipped them, and a Cammy Heroclix, my Stardew Valley farm is starting to look awfully tidy.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.