X-COM creator Julian Gollop discusses his most important games

X-COM’s maker remembers over 30 years of perfecting the turn-based tactics genre.

Did you know Julian Gollop has written four columns for us, including subjects like the creation of the deck builder genre? Find them all here.

This article was originally published in issue 313 of Edge, an extremely good magazine about computer games. Subscribe here in print or digital.

Of a generation of early British game creators, only a handful are still making games today. Still fewer have threaded their careers through so many of the tectonic shifts and revolutions in business and technology that have driven the game industry since. And even fewer also have so much still to look forward to. But Julian Gollop, designer of strategy classics Rebelstar, Laser Squad, and his most celebrated game, X-COM, can claim a career that has lived all of it.

Gollop started out coding games in BASIC while at school, translating his passion for strategy board games to computers. He’s self-published games and founded several studios. He’s watched publishers rise and fall, and worked within one of its largest. He was a pioneer of DLC, has worked with launch hardware, jumped into crowdfunding, and has explored the frontiers of developing for Early Access.

And through it all, as trends have waxed and waned, he has refined and polished to a sheen a personal fascination for a particular kind of game: turn-based squad tactics. As he continues that grand project with Phoenix Point, he looks back on the games that have brought him to today.

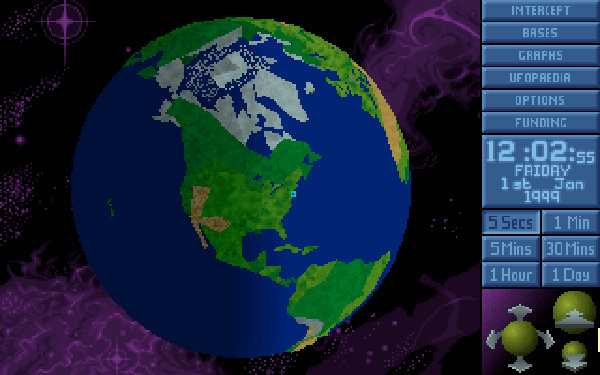

Rebelstar Raiders

Developer: Julian Gollop

Publisher: Red Shift

Format: ZX Spectrum

Release: 1984

"Rebelstar Raiders came about because I wanted to implement some of the board games that I played years earlier, like Sniper and Squad Leader, which were all about squad-based tactics and true line-of-sight shooting. I thought it’d be great for a computer to do this instead of having to calculate it by hand, but I was not the best programmer in the world. Rebelstar Raiders had a one-screen map and each soldier was a single little character that moved in 8x8-pixel character jumps. The thing I needed was a shooting algorithm. I wanted a line of pixels to extend and shoot the enemy with a bit of randomness. A friend who was an expert in machine code wrote a little bit of code for me called Zap, and with it I could draw a line between two pixel positions and define what it hit at the end.

I was working with a group of friends who had a company called Red Shift. They were producing adaptations of board games, like Apocalypse for Games Workshop, and Rebelstar Raiders sold very well for them, compared with their other games. There was clearly an audience for that style of game, even though it was twoplayer only and included only three maps.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Rebelstar Raiders was the beginning of a long line of games that resulted in X-COM.

Julian Gollop

As I made Rebelstar Raiders I thought of a number of things I wanted to add to my tactical combat system. I wanted opportunity fire, or overwatch as it’s commonly called now. It was a core mechanic in the board game Sniper, and made it really interesting because it adds an element of anticipation. The player had to plot exactly where they were going to wait, predicting what their opponent was doing rather than just reacting to them. I introduced that in Rebelstar. I also wanted inventory management, so your soldiers could use different types of equipment, especially grenades. I wanted more sophisticated rules relating to wounding and morale and stamina and stuff.

These things were important parts of the overall mechanics in Squad Leader, and they weren’t just about physical destruction but how well your troops performed under pressure. And I wanted to refine the explosions and destructibility of terrain, because modifying the game’s environment through the effects of battle was, I felt, very important.

It’s true to say that Rebelstar Raiders was the beginning of a long line of games that resulted in X-COM and now ultimately Phoenix Point. It’s a tactical combat system that I continued to refine over time as my skills improved."

Chaos: The Battle of Wizards

Developer: Julian Gollop

Publisher: Games Workshop

Format: ZX Spectrum

Release: 1985

"I originally designed Chaos as a board game after seeing some of my friends at school playing a Games Workshop game called Warlock. It was basically a card game with static wizards, so I thought, ‘Well, I’m going to make a better game than this.’ The real innovation that I was so pleased I came up with was that when you summoned creatures from your hand of cards, you actually placed the card on the board and then moved it around like a playing piece.

That was before home computers existed, so when I got my ZX Spectrum one of the games I really wanted to implement was Chaos. It was the third game I programmed entirely by myself, but the first I coded purely in assembly language, and the first with artificial intelligence, so it was a big step up for me. You could have up to eight wizards in the game; I primarily saw it as a multiplayer game in which all of them could be AI-controlled. The really nice thing was that this allowed players to play semi-cooperatively versus the AI before they fought each other to be the final victor.

I was pretty faithful to the original board game, but one thing I added, which could only have been done on a computer, was the idea that creatures could be summoned as illusions or real. If you summoned as an illusion it was guaranteed to succeed, otherwise it was a percentage chance, but the other wizards could ‘disbelieve’ it. It introduced an interesting game of bluff and counter-bluff with other human players and was still playable around one computer with one keyboard. To cast your spells you had to cover your hand to secretly press the keys to maintain the element of bluff.

Unfortunately, it had a number of bugs, and some were slightly weird. The notorious one is the Turmoil spell. It randomly repositioned everything on the entire map, but I thought it wasn’t very useful or good, so I left it out of the initial spell allocation system. But there was another spell called Magic Wood, which a wizard could use to randomly be given a spell, and there was a chance that’d get Turmoil. When they cast it, players reported the game crashed after trying to move everything around the map for five minutes solid. I don’t know why; I never tested it thoroughly because it wasn’t supposed to be there. The spell became a rare and legendary thing you’d be lucky to see. ‘Have you seen the Turmoil spell in Chaos?’

Chaos was one of Games Workshop’s first original computer games. I was desperately trying to finish it because I’d started my university degree at London School Of Economics and I needed to get on with studying, and I have absolutely no idea how well it sold. I was paid some money for it, but I don’t remember seeing any royalty statements, and I resolved from that point on that I was going to do my own deals. The next game I did, which was Rebelstar, I took directly to Telecomsoft and it was put on their Firebird label. It still wasn’t the best business negotiation because I got 10p a copy and the game retailed at £1.99, but Rebelstar did well and my first royalty cheque was £6,000 or something. I bought a nice electric guitar, the first thing I could think of, and I left university."

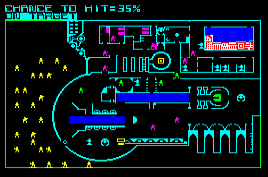

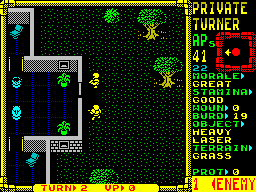

Laser Squad

Developer/Publisher: Target Games

Format: Amstrad CPC, C64, ZX Spectrum

Release: 1988

"When I left university I set up a company with a friend called Target Games. The idea was to make a new squad-based tactical game. It was an evolution of Rebelstar with the difference that it was going to include hidden enemies which were only revealed by line of sight. Battle is about evasion and detection, about this tension of trying to find the enemy while at the same time avoiding detection yourself. For me it’s a fundamental part of how squad-level tactics should really work in a game.

Each soldier had a facing, so if you came across an enemy looking away from you, you could see them and they couldn’t see you. This gave the opportunity to dive back into cover to avoid detection or to take a shot. That idea was married with opportunity fire so you had to decide which way you wanted your soldier to face to anticipate where an enemy might come. It was an evolution of every game I’d made previously, but really, for the first time it was no longer a game of chess. It was about anticipation and prediction and bluff. Really, Laser Squad is the foundation of the tactical system in X-COM.

My friend left, so my brother Nick joined. I’d nearly finished working on the Spectrum version, he started working on the C64 version, and then we did a Amstrad CPC version of the game. We did all the 8bit formats at the time, and we were self-publishing so we got the boxes made, printed, we had them sent off to the distributors, we paid for a bit of advertising. We were in business.

The other innovation we put in Laser Squad was a business one. In the back of the rulebook there was a coupon you could send off with a postal order or cheque to buy an expansion kit on tape, which came with two extra missions that you’d load after you loaded the main game. The idea was that we’d produce a series; it sounds very basic, but we thought it was an amazing innovation! It was a good business model for us because all we had to do was to manufacture them very cheaply and do a bit of postage; me and Nick would come into our little Harlow office in the morning, get all the orders in the post, take the tapes out of the boxes, put them in bags and address them and we had a franking machine and took them to the post office. Then we’d start coding for the rest of the day."