X-COM creator Julian Gollop discusses his most important games

X-COM’s maker remembers over 30 years of perfecting the turn-based tactics genre.

X-COM

Developer: Mythos Games

Publisher: MicroProse

Format: Amiga, PC

Release: 1994

"We realised we needed to step up our game. From our point of view, the future of strategy games was going to be on PC, primarily because of the stuff coming out of the US, especially by MicroProse, like Railway Tycoon. We’d made a demo for Laser Squad 2 on the Atari ST, but we really wanted to make it for PC and we took it to a list of three publishers. At the top was MicroProse. The reason was obvious: they did Railway Tycoon, and Civilization had just come out. It was 1991, and they were simply the best computer game developer and publisher in the entire world, and Sid Meier was the best game designer.

We thought it was a long shot. Why would they be interested in what we had to offer? And we were also a bit worried because we’d never actually made anything on PC before. Atari ST was as close as we’d got. So we took the demo to MicroProse UK and one guy there, Steve Hand, was a big fan of Laser Squad and he really wanted MicroProse to do the game. But he was struggling to get them to accept it, so they came back to us with a proposal for something much bigger as a game concept. In particular, they wanted something that could match Civilization in scope and complexity, because MicroProse US rather disparagingly regarded MicroProse UK as the toy division.

They were very keen for the setting to be based on Gerry Anderson's UFO TV series.

Julian Gollop

The primary requirements were a Civilopedia and a Civ-like tech tree. Which was fine. They were very keen for the setting to be based on Gerry Anderson’s UFO TV series, because they were big fans of it, and from that we took the concept of X-COM itself, because in the TV show there’s something called SHADO, which is this worldwide organisation trying to prevent infiltration of UFOs on Earth. They had Moon-based interceptors and aircraft interceptors, and if the UFO got through they had a ground-based interceptor, a ridiculous-looking vehicle. We didn’t have the Moon-based interceptors, but the concept went straight into X-COM: we had aircraft, and you could send your ground squad to tackle UFO landings.

What we didn’t take were the aliens themselves. They were, disappointingly, exactly like human beings. So I looked at some UFO folklore, in particular a book called Alien Liaison by Timothy Good, which contained all this juicy stuff about abductions by greys and cattle mutilations, reverse-engineering captured UFOs, shady deals between governments and hybrid aliens. It was really good. I just took it all and put it in the game as well, but the graphics came from the imagination of John Reitze, who was the main artist. Steve Hand and I looked at a screenful of sprites and we decided which were the most interesting-looking ones and they went in the game. I had to retro-fit what they actually did; it was quite an eclectic mix which didn’t really seem to fit together!

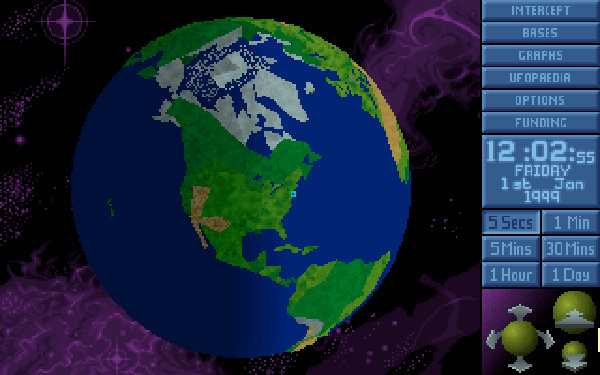

From our initial meetings at MicroProse I quickly wrote the original design document. Although it was a bit sketchy, only about 12 pages long, the final game is very close to it. I came up with the idea of the Geoscape, a globe that is your main strategic planning device, and that you have things flying around and cities and countries. I hadn’t really fleshed out how interceptions would work but everything was there in terms of funding from countries, and UFO activity in different regions; you had to deal with it or it’d affect your funding. Aliens could take over countries. There were terror missions.

There was the idea of looting stuff and reverse-engineering it. That was all there in the document. But MicroProse initially struggled to understand the game. I had to go to a very large meeting with 12 people there from marketing, game designers, senior producers, and I had to explain it to them. It must have worked, because we got the contract signed very shortly after that. We were away.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The original game was made by me and Nick, and a couple of artists, and that was it. A sound designer and musician came in at the end of the project. The Geoscape and the Battlescape didn’t come together very well until very, very late in the project, partly due to problems with our scheduling. We had monthly milestones planned and we were going to spend several months on the tactical side and then 11 months on other side. We started working purely on the tactical game but we didn’t finish it before we started to work on the Geoscape, and we didn’t get them working together at all until about four or five months before the game was finished, and then it really was a bit of a mess.

Still, testament to the original vision being quite good, it did end up pretty much what I wanted it to be. Really, it’s a question of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, because once you started getting the interaction between the strategic and tactical it really felt like you were in command of an organisation. Everything you did made a difference and had an impact on the future. If you lost a solider it was bad, or you might get a lot of loot from a mission that could really boost your research and manufacturing. It was cool. I mean, there were certainly problems, like the micromanagement of resources, and you had to equip your soldiers every time. But in terms of the core mechanics of the gameplay I was really happy with the way it turned out.

Sadly, it wasn’t the case for MicroProse, because in 1993 they were taken over by Spectrum Holobyte. Spectrum Holobyte visited MicroProse UK and they told them to cancel a bunch of projects. They took one look at X-COM and said it looked real crap. ‘Stop working on this rubbish right away.’ But there was a lot of support for the project at MicroProse UK by this stage and they defied their new rulers in the US and kept the project going. They didn’t tell us it had been cancelled. That would’ve worried us, for sure.

Then it came back on Spectrum Holobyte’s radar. They’d required MicroProse UK to deliver a project for their end of quarter to meet financial projections. So MicroProse UK told them that X-COM was still going and it could be ready in time. They said, ‘OK, fine, we need something.’ But it put a lot of pressure on us, because suddenly we really had to finish it by end of March, and they required us to work in-house in Chipping Sodbury seven days a week, 10 hours a day for several months. They didn’t give us any extra resources. In fact, we had to beg them to give us a more powerful computer to use, because my brother’s computer couldn’t handle it! My computer was having serious overheating problems. I had to remove the case and it crashed occasionally. They begrudged us one new computer for Nick and they stuck us in this tiny little room. We just had to crunch.

X-COM: Enemy Unknown was a really big success for them. So of course they wanted a sequel and said they needed it in six months. We said, look, we can’t do anything meaningful in six months. The best we can do is a minor update to the game. We wanted to do something much more ambitious. And they said, ‘Right, fine. Why don’t you license the code to us to do the sequel and you can work on the third one in the series.’ So that’s how Terror From The Deep became the sequel, and it was done entirely in-house at MicroProse, using all our code, which they didn’t change very much, and we worked on X-COM Apocalypse, which was released in 1997.

It took them longer than six months to do it. I think it was about a year. That told them. And they had a large team on it! I remember visiting them when they’d just finished the gold master and they had a bit of a celebration meeting, and there were 15 people there. I was like, blimey, this is a big team! Wow, if we had that amount of resources for a year we could’ve done something amazing! And all they’d done is a reskin of the original game? Good grief."

Magic & Mayhem

Developer: Mythos Games

Publisher: Virgin Interactive

Format: PC

Release: 1998

"We switched publisher to Virgin Interactive and we had a four-game deal with them. The first project was going to be Magic & Mayhem, and the idea was to create a wizard casting game, loosely inspired by the original Chaos but this time with a realtime game system and a campaign structure where you’d go from one region to another fulfilling various mission objectives.

We put a lot of effort into the core mechanics of the spellcasting, where you combined items with Law, Chaos or Neutrality talismans to create different spells at the beginning of each level. It was a nice game system, but the singleplayer aspect of the game was a bit of a struggle. It was almost an afterthought, and we wanted to have a much more heavy RPG flavour to the game so you could customise your character, a lot more progression systems.

Virgin Interactive really pushed back against this. We started to make it before Diablo came out, and it was also before Baldur’s Gate, which was the real milestone in RPGs. They said RPGs don’t sell, which was, of course, complete rubbish. They wanted to make it much more RTS-focused, partly because of Command & Conquer, which was very popular at the time. They took us on a trip to Las Vegas to have an audience with Brett Sperry, who founded Westwood Studios, to get his input.

They required us to work seven days a week, 10 hours a day for several months.

Julian Gollop

One of the things we struggled with was how to generate the art. It was a bit crazy but we had this idea that we’d make all the creatures out of plasticine, put an armature inside them and do stop-motion animation, putting them on a turntable and to take shots of them from eight different angles with a video camera for each pose. Then we’d process the images in Photoshop, replacing the background with blue and shrinking down to the sprite.

It sounds a nice simple system, but we had an absolute nightmare in the cleanup of all the graphics. We had to employ people to process them and there were so many mistakes, including losing entire sequences of images. Each creature had a death sequence which usually meant the destruction of the model itself. We found there were some animation problems, some things we’d forgotten to do, and we couldn’t go back and do them because the model had been destroyed! So it was just crazy.

It also had a difficult release. Virgin Interactive weren’t doing too well. Westwood Studios had been sold to EA and they had to do a deal with Bethesda, who were helping fund the game, and they sold it in the US. It sold okay in Europe but not so well in the US, probably because by the time it was released the graphics were looking quite dated and the game system didn’t know what it wanted to be. It had RPG and RTS elements but they weren’t really there. It was a difficult project which didn’t work out so well, though quite a lot of people liked it."

Ghost Recon: Shadow Wars

Developer: Ubisoft Sofia

Publisher: Ubisoft

Format: 3DS

Release: 2011

"After I had finished Rebelstar Tactical Command on GBA I had the intention to go to Bulgaria and take it easy for a while and just explore the country and catch up on games and reading. But I got a bit bored! I had some projects I was planning to do but I realised they’d be a bit too difficult to do on my own and I missed working with a creative team. So when I heard Ubisoft were setting up a studio in Sofia, I applied and I was hired as a game designer in November 2006.

The first project I worked on was Chess Master, which was a bit strange because I thought chess had already been designed, but we produced some interesting minigames. Very quickly I became a producer because the studio was so inexperienced. I worked on various projects, many of which never saw the light of day, all for Nintendo DS, but we also made several pitches to Ubisoft’s editorial office. One of them was Ghost Recon meets X-COM for Nintendo DS.

Luckily there was a fan of X-COM on the editorial board and he really liked the idea. At the time they were working on a new Ghost Recon game and Ubisoft had this cross-platform simultaneous launch strategy. It didn’t matter if the games were different but one requirement was that the stories had to be related. Our game would be a ‘sidequel’ to the main console game, Future Soldier, and a turn-based strategy while theirs was an action game.

But then Ubisoft started to insist that we did certain things that didn’t make much sense. The console version had this weird concept, ‘united we are stronger’, so as a squad of four you could go around together shooting things and one player would control the movements of all four and the others would do the shooting; the idea was they had combined special powers in this formation.

It was a weird idea; I didn’t really understand it, and from Shadow Wars’ point of view it didn’t make sense because one thing you really shouldn’t do as a squad is move around together because you’re vulnerable to explosives, and it’s also a bit boring. We tried to push back, and then I got a call saying that we didn’t have to worry any more and that we could make it the way we wanted. I later found out that they cancelled Future Soldier to completely reboot it. But they couldn’t reboot our game because by this stage we’d transitioned from DS into a 3DS launch title.

That was really tough, because when we finally got Nintendo’s 3DS SDK it was like a circuit board in a cardboard box. It was very unfinished. Fortunately, we’d made a very good decision early on in the project to build everything on PC using XNA and C#. Our idea was then to translate it to DS. So suddenly switching to 3DS didn’t have a big impact on us, though it was a struggle to make the engine work on the SDK hardware.

Then, very late in development, Nintendo dropped the bombshell that the 3DS’ upper screen was stereoscopic 3D. They kept it secret from all the development teams because they didn’t want it to leak! Beforehand, we couldn’t figure out why the upper screen was larger than the lower screen, which for us was the primary screen because of its stylus input, and the upper screen was for information. Oh crap, we thought, we had to swap our screens around and forego stylus input. It wasn’t such a big transition but it was a shock because it was so close to launch.

My boss was completely wrong, as he was about many, many other things.

Julian Gollop

Something I’ve never talked about is that the first prototype we produced was much more X-COM-like than the final game. It had a strategy element and the tactical game was more like X-COM. It had overwatch and more sophisticated systems, and it also had a two-action point system, almost exactly the same as the one in Firaxis’ XCOM! We thought it was an interesting concession to making it more playable. But when we presented it to the editorial board, they had a really negative reaction. They said it looked far too much like a PC game. I said, ‘Well, we did pitch it as X-COM meets Ghost Recon! We can really make this work.’ But they said, ‘No, there’s only one kind of strategy game on Nintendo handhelds and that’s Advance Wars. If it isn’t like that, it isn’t a proper handheld game.’

So we had to go back and make it like Advance Wars. I made the interface very similar, while retaining the squad-based mechanics that we wanted. I think we did quite a good job and maybe the editorial board were right to make it more familiar to Advance Wars players.

We were worried it was a bit too basic, but it seemed to go down quite well with many players. Unfortunately, the launch of the 3DS itself wasn’t a success, partly because its price was out of whack with what the market expected and the launch lineup was really lacklustre. Nintendo fixed these problems but my boss was opposed to doing a sequel. He said the 3DS was dead and that we had to go with the PS Vita so we worked on Assassin’s Creed Liberation. I love Nintendo handhelds and I’ve made two games for Nintendo. It’s a shame I wasn’t able to make a follow-up to Shadow Wars. And then the 3DS ended up a success and the Vita wasn’t, so my boss was completely wrong about that, as he was about many, many other things."

Chaos Reborn

Developer/Publisher: Snapshot Games

Format: PC

Release: 2015

"In 2010, 2K announced the game that was eventually called The Bureau: XCOM Declassified. There was a big backlash against it by fans, saying it wasn’t the game they wanted. I was also infuriated and I thought, ‘Right, that’s it, I’m going to do my own version of X-COM’. I wanted to do my own thing again and was going to crowdfund it. In 2011 I started to put a team together for it and planned to leave Ubisoft.

But then Firaxis announced their XCOM. I was utterly, utterly dismayed. I thought my plans were basically torpedoed. I believed that if anyone could do a good job with the franchise it surely had to be Firaxis, they’d do it properly. And they did. So I thought, ‘OK, let’s not do that, let’s do a reboot of an earlier game’, because it’d be a smaller project and easier to do. I picked Chaos because it was a favourite of mine.

We established a new studio, Snapshot Games, and did a Kickstarter campaign. A lot of the supporters were fans of the original, and it was a really nice project to work on. We encountered a dilemma, though, because the game is multiplayer-focused. I think it worked well as that, but the singleplayer game not so much. It’s just not so interesting fighting against an AI: the bluff mechanic doesn’t work so well, you don’t get this emotional rollercoaster of the strange behaviour of other players. So a group of fans were really keen on the game but it didn’t reach much of a wider audience.

One of the other problems was that the random-number stuff was really too brutal for a lot of players to handle. It was really extreme, especially in the combat. Based on a single percentage, you either killed the enemy or you didn’t. Of course, for experienced players it’s all about managing your risk and assessing that on percentages, and one of the obvious ways to mitigate your risk is not to get your wizard in range of being attacked, because anything can kill you in one hit. We found a lot of players simply couldn’t get this at all. They assumed their wizards can soak up damage. It makes the game really dynamic and exciting for people who get it, but we were getting these negative reviews about RNG and so we spent two or three weeks on a reduced RNG version. It worked quite well but of course it split our playerbase.

Obviously X-COM also faced this problem. One of the biggest complaints is when an enemy is right next to a player and they’ve got an 85 per cent chance to hit and they miss. ‘That’s absolutely ridiculous!’ People ragequit and never play again. It’s an issue they partly solved in XCOM 2, and we had another mode in Chaos Reborn. It’s a rather sobering lesson in game design and how people manage random factors. Still, it sold well enough for us to start work on the next game, Phoenix Point. So from that point of view it was a success, to lead to the next game."