Unraveling the curious history of videogame mazes and labyrinths

Wandering not lost.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 355 in April 2021. Every month we run exclusive features exploring the world of PC gaming—from behind-the-scenes previews, to incredible community stories, to fascinating interviews, and more.

The history of mazes and labyrinths is a maze itself. The first recorded labyrinth was commissioned by the Egyptian king Amenemhet III thousands of years ago: unlike the Minotaur labyrinth of Greek myth, this was built to be lived in, with banqueting halls, temples, and offices. Since then, mazes have been cut from turf, mosaicked on cathedral floors, stamped on coins, hacked into cornfields, formed by parking tourbuses, and fashioned from hedgerows as dallying spots for English aristocrats.

Mazes and labyrinths generate a surprising range of emotions. Partly, this is because the former isn't quite the same as the latter. The associations of the noun 'maze' are largely negative, referring to bewilderment, deceit and worldly distraction. A labyrinth is a similarly confusing structure, but the word has acquired more positive senses over time—it can serve as a place for reverie and contemplation. Psychotherapists like Dr. Lauren Artress have even prescribed labyrinth-walking as a form of meditation. Integral to this distinction is the idea that while a maze may have many paths, a labyrinth has only one, however winding.

Off the map

For a time, mazes and labyrinths were central to videogames. The original first-person shooter was arguably Maze (1974), created by students on Imlac computers at a NASA laboratory. While not the first of its kind, Namco's Pac-Man spawned a wave of 2D arcade maze-chase games in the 1980s. "I think a lot of how we understand moving through 3D spaces in videogames today comes from maze-like experiences," notes Holly Gramazio, game designer, curator, and scriptwriter for Dicey Dungeons, who once organised a maze exhibition for London game festival Now Play This. "Even going back to the Windows 95 screensaver maze, right? A lot of early 3D, even if it wasn't explicitly labelled a maze, is something that we would now consider maze-like."

Mazes and labyrinths are a good introduction to 3D movement in games, Gramazio points out, because the premise speaks for itself. "You see them and you know what you have to do." They can also be a powerful "design prompt" she adds, in that they show how many different imaginative contexts and perspectives you can tease out of an ostensibly small area.

Computer simulations offer more elaborate possibilities for maze- builders, of course: they aren't bound by everyday physical conventions. In Alexander Bruce's Antechamber, ascending a flight of stairs may leave you on the same floor. In Ian McClarty's The Catacombs of Solaris, stopping to look around morphs the corridor ahead into a wall.

Even going back to the Windows 95 screensaver maze, right? A lot of early 3D, even if it wasn't explicitly labelled a maze, is something that we would now consider maze-like

Holly Gramazio

For all these precedents and opportunities, however, mazes and labyrinths aren't much celebrated in games today. Maze environments are inherently artificial and arcane, and it's difficult to fit them into many stories and settings. But the real problem, perhaps, is that mazes and labyrinths aren't that fun to navigate—at least by the standards of games that define 'fun' as a brisk feedback loop between task and reward with minimal ambiguity or downtime.

"In a digital maze, you cannot separate people's frustration at their inability to find their way out from their frustration with the interface and how the maze is presented," Gramazio explains. "When people are stuck and can't find their way out, I think overwhelmingly the response is 'This is bullshit, I can't figure out where I'm going'. It's not 'OK, this is very clever, I need to stop and think about the choices I've made'. Getting people to feel comfortable and confident in their navigation of complex digital spaces is already quite difficult." Gramazio herself enjoys thinking about mazes but is less keen on walking them, in real life and otherwise. She came close to abandoning her first Final Fantasy game, Final Fantasy VIII, thanks to a maze section where the same backdrops are used for different rooms. "I was in some kind of drain for fucking ever. I was in a drain that was basically the same four pictures of a drain representing 40 different places they could be in the drain."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Blind corners

Mazes and labyrinths might seem obnoxious in a role-playing game with random battles, but that claustrophobia makes them well-suited, of course, to horror games. Even here, though, developers can't afford to bewilder players too much. "I think there's probably a lot of great inspiration to draw from studying real-life mazes and labyrinths, but my guess is that most of it would be connected to aesthetics and general layout, and not so much about level design," comments Fredrik Olsson, executive producer and creative lead on Frictional's Amnesia: Rebirth. "In fact, most real-life mazes could act as examples of really poor level design—that's part of their nature."

Amnesia: Rebirth contains one of gaming's more horrible mazes. Dropped on you around the halfway mark, it's a grid of square pillars with paths formed by articulated metal gates linked to pressure panels.

Amnesia: Rebirth contains one of gaming's more horrible mazes. Dropped on you around the halfway mark, it's a grid of square pillars with paths formed by articulated metal gates linked to pressure panels. As elsewhere in the game, you can light torches to quell your character's mounting panic, but this risks attracting attention. There's a creature in the maze with you—half-human, like the Minotaur. As you explore you hear it ranting, growing more and more enraged as you near the exit.

Considered from on high, the maze isn't too demanding. It's closer to a single-path labyrinth than a maze, and there are unseen fail-safes (which I won't spoil) to help you reach the end. Paradoxically, mazes make it easier to add such handholds without damaging the illusion: as Olsson explains, developers can "capitalise on the confusion that naturally comes with the introduction of a maze [...] to cheat the player in a helpful and discreet manner". During Rebirth Let's Plays, he observes, many YouTubers don't realise that they're making progress till they burst through the exit door. "[It] might feel like the design was extremely confusing and that they were just lucky. But [this is] actually a result of some subtle cheats that, at the right moment, simply open a way forward for the player, without them noticing."

Problems of influence

There are less obvious reasons to be appalled by Rebirth's maze. The pillared layout takes limited inspiration from the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, a 19,000 square metre landscape of regularly arranged concrete slabs. The association, which I didn't notice during my playthrough, risks reducing real suffering to an aesthetic prop, though this claim obviously relies on you knowing about the game's creation. It's also a bit of a judgement upon the original monument—often described by journalists as a maze or labyrinth—which has been criticised for portraying the dead as a mass of interchangeable objects, burying their names in an exhibition beneath the monument. It's disturbingly easy to read as 'pure' architecture that can be readily transplanted into a different context. Olsson's insistence that the memorial doesn't have "any actual connection" to Rebirth's events feels like a testament to this process of abstraction. "It was inspiration purely related to the spatial structure."

If there's no literal connection between the Holocaust and Rebirth's events, themes of dehumanisation and genocide abound in the game's narrative. In Amnesia's universe, terror is a kind of energy resource. As you'll learn if you read story artefacts in a control room just before the entrance, the maze was explicitly built to maximise the dread of the unlucky wanderer before 'harvesting'. The space explicitly objectifies you, in other words: it disregards your personhood and reduces you to your capacity for fear. The control room also contains a broken maze model that once allowed the layout to be changed for optimal effect. Peering down at it helps you imagine both the frenzy of those caught inside and the indifference of those pulling the levers.

Lab technicians

It's a far cry from the mentalities of amateur maze-builders online, many of whom do their finest work in sandbox editors such as Minecraft. These players try for more uplifting experiences: perplexity, yes, but also mystery, wonder, and the satisfaction of reaching the exit square. Indie designer and Sony/Kuju Entertainment alumnus Robert Swan has been exploring mazes since the days of MIDI Maze on the Atari ST (the latter's splitscreen PVP mode allows you to spy on your opponent—when playing with his brother, Swan used cardboard to block the view). He cut his teeth as a designer making games with Sony's Net Yaroze console at university, later gravitating to map creation in shooters like Quake and Counter-Strike. He also occasionally creates mazes from illustrations drawn by his partner Jodie Azhar, Teazelcat Ltd CEO and a former technical art director at Creative Assembly.

I think Minecraft always guides people to mazes as the simple orthogonal nature and procedural scenery looks maze-like to start with.

Robert Swan

"I was an avid builder in Minecraft for many years along with my brother, and we built a maze just like everyone else on our continent," Swan says. "I think Minecraft always guides people to mazes as the simple orthogonal nature and procedural scenery looks maze-like to start with."

Talking to Swan reveals the diversity of approaches to maze building, some of which chime intriguingly with more mundane level-design questions. There are 'weave mazes', for example, where the paths loop under or over each other, which is a popular gambit in some multiplayer shooters. 'Braid mazes' have many paths but no dead ends. These can be especially tough for players, Swan notes, because "mentally we never 'close off' parts of the maze as solved". And then there are Recursive fractal mazes that harbour perfect smaller copies of themselves. "I think I've seen this touched on in some games but it can quickly spiral out of control in complexity—I haven't seen such a concept applied to a multiplayer first-person shooter, but it would be a fascinating experiment!"

For Aris Martinian, a 21-year-old musician, mathematician, and author from Massachusetts, the trick to maze design is giving the player the sense that they're getting somewhere, however sprawling and knotty the structure. Martinian draws a comparison with incremental games such as Cookie Clicker. "Even if the entire game revolves around clicking a single cookie and watching numbers go up, unlocking new things keeps the game interesting, and each buy gives the player the same satisfaction as solving a single sudoku puzzle. So when I build mazes, I like to provide landmarks, not just for ease of navigation, but also to capture that sense of progression."

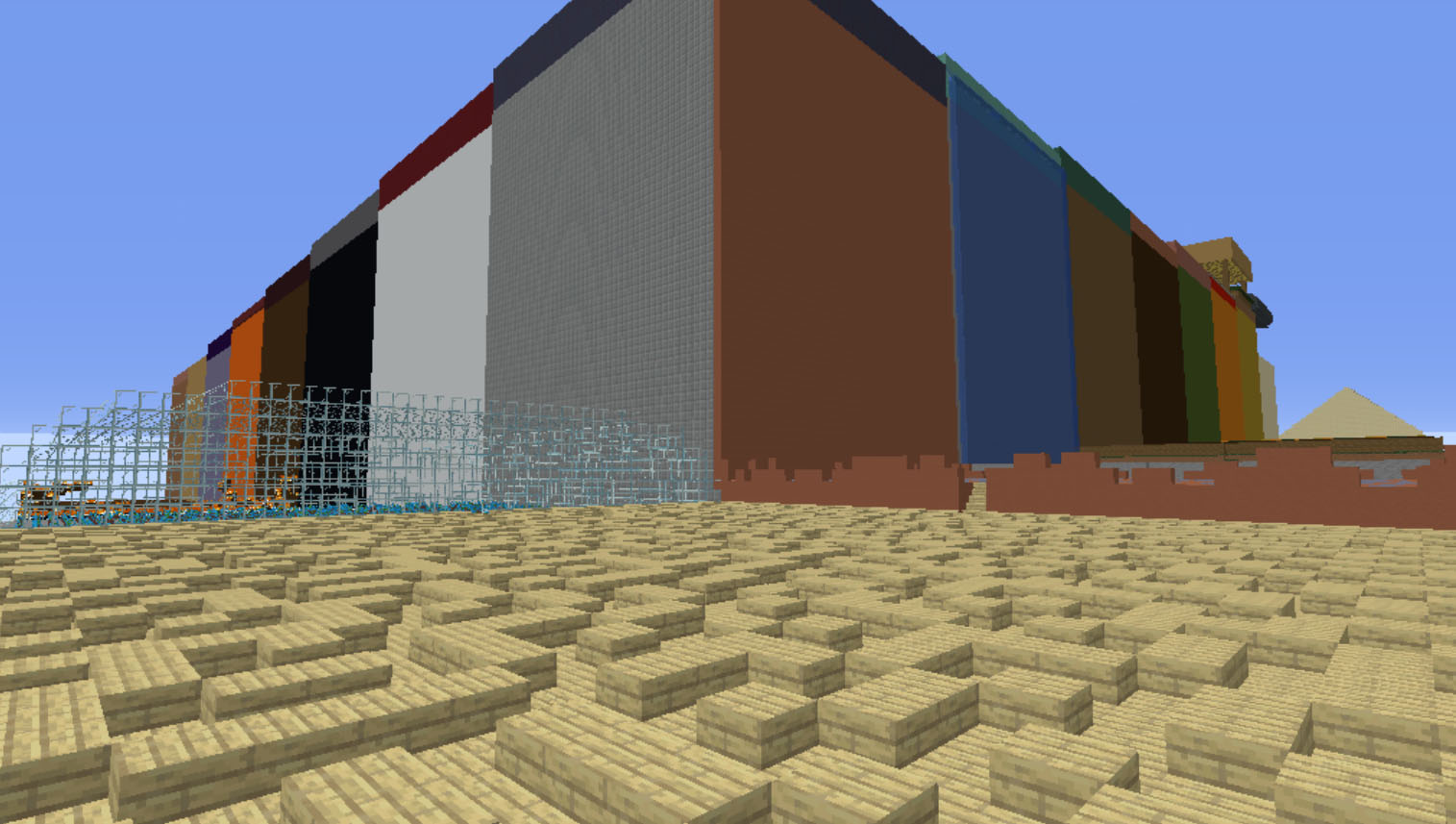

Martinian has been building Minecraft maps since the young age of 13. If you have a poor sense of direction, their mazes may sound like the stuff of nightmares: highlights include the formidable Prismatic Puzzler, a seven-storey coloured glass tower that resembles a Death Star focusing array. But if Martinian's mazes are mind-boggling they are also considerately built, with bridges providing vantage points and a range of strong landmarks. All are designed to teach some measure of spatial reasoning and problem-solving. "When a maze has you doing this, instead of just blindly hugging the right wall and hoping you eventually reach the exit, I consider that a great success."

Built to last

DeuxiemeCarlin from Louisiana is the holder (at the time of writing) of the world record for Minecraft's largest published maze. His magnum opus, Warped Trails, is a stratospheric endeavour that took around a month to create and has been successfully traversed by just seven out of thousands of players—the fastest run is around seven hours. DeuxiemeCarlin has been captivated by mazes since infancy, and is happy to make them out of anything. "Any material that can be twisted to form paths, I can develop a maze through: everything from a stack of DVDs to a Discord server to white furniture!" He enjoys mazes both for the joy of solving them and for their visual intricacy. "One theory I'm leaning towards in recent months is that it has something to do with the way my brain works, with high- functioning autism. And who says it has to be one [reason], but not the others? It could be a multitude of things!"

DeuxiemeCarlin considers maze- making an artform. "The same feeling people get when finishing a painting, or when composing music? That's the feeling I get when I make mazes." He emphasises the importance of variety—Warped Trails consists of 100 regions with different colour palettes and materials—and also advocates against repeating patterns or stretching out hallways for the sake of filling space. "Each region must be crafted with care, and attention to detail."

Elusive wording

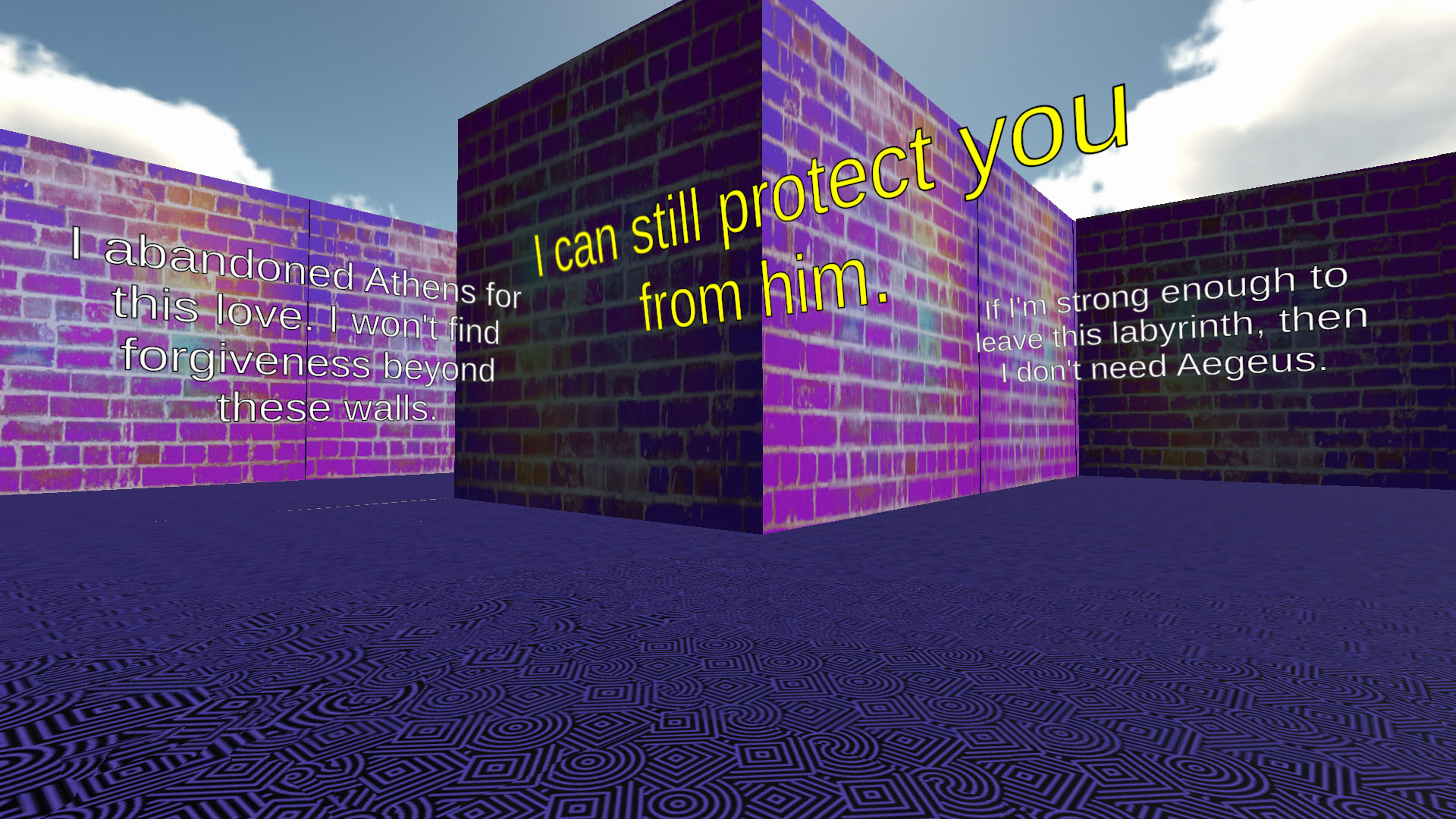

Mazes don't have to be physical structures or representations, of course. Some of the best are text-based. Itch.io is full of Twine games that are inherently labyrinthine, composed of many branching strands, and playing them is like fumbling around a maze with a blindfold. Sisi Jiang's Theseus seizes upon this comparison, while also embracing the mixed feelings mazes and labyrinths attract. In this retelling of myth, the Greek hero Theseus and the Minotaur are estranged partners rather than foes. Cast as Theseus, you must find your way out of a garishly painted labyrinth while playing out an imaginary argument with your beau.

The maze embodies the parental abuse experienced by both characters (the Minotaur, aka Asterion, is the sort-of-foster son of the king who imprisoned him). "It was meant to give the player tunnel vision, a feeling of a loss of control, and claustrophobia," Jiang explains. "It was important to me that a bad relationship did not solely involve the actors in the play, but the conditions under which they were meant to forge a connection."

But the game also presents its labyrinth as "a space for emotional exploration" and "an emotionally secure place for failure". Each path corresponds to a branch of Theseus' internal wrangle with the Minotaur, displayed as floating text. 'Wrong' paths uncover the tenderness each character still has for the other, together with futile efforts at reconciliation. In the process, something essential is revealed about both human beings and the things we build. "[There are] no consequences for 'picking incorrectly' the first time," Jiang says. "And I think that accurately reflects a lot of our human internal processes—we have to hit tons of dead ends before reaching our truth."