The art of flavour text

How developers use in-game descriptions to bring worlds to life.

What is a pendant? In Dark Souls, it's one of the items you can choose to take when you roll a new character, and it comes with the following description:

"A simple pendant with no effect. Even so, pleasant memories are crucial to survival on arduous journeys."

"An item in a game that has no purpose? Psha!" Ryan Morris, an English translator for the Souls series at localisation studio Frognation, imagines the thought process a new player goes through as they read it. "Gears in brain start churning. And what's this about a tough road ahead? Oh, probably nothing. I should be done with this game in a couple of days, at most." Even before Dark Souls has started, its dark magic has wound itself around another hollow, all through the power of flavour text.

Every item in the Souls series has text associated with it, accessed through the inventory, describing the item and hinting at its function or place in the world, and maybe other stuff as well. Dark Souls' use of flavour text is an exemplar of the form, a demonstration of how a world can come to mouldering life, simply by reading apparently disassociated paragraphs in a random order.

Which is weird, when you think about it. Flavour text is part of a game and yet not part of it. It sits on the sidelines and it's also fundamental to your understanding of the game. And it's everywhere, from 4X strategy games to action RPGs, first-person shooters to collectible card games.

Trivial or essential?

"...a causal loop within the weapon's mechanism, suggesting that the firing process somehow binds space and time into…"

Vex Mythoclast, an exotic-class fusion rifle from Destiny which fires without needing to be charged

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"Personally, I think that flavour text is text, not dialogue, that is superfluous to the functionality of game, and it usually gives some hints at the lore," says Morris. "It's story text. It's extra information that often serves to start to build the world so you can start to imagine some of the things that aren't shown explicitly." He pauses. "It's fun text."

"Flavour text implies two things," says Alexis Kennedy, founder of Sunless Sea dev Failbetter Games and maker of narrative card game Cultist Simulator. "It suggests it's trivial and that it's essential. On the trivial side it's like grouting, it's the bits you put in places so you've got something of value everywhere, something you put in between things that matter more. In the other sense, a work without flavour is tasteless, boring, so flavour text is what provides most of the sense of a setting, of being there."

Depending on who you talk to, flavour text is strictly the equivalent of the italicised text on a Magic: The Gathering card, or it can be broader, edging into dialogue you hear from a shopkeeper, which is how Kennedy looks at the way it can be expressed in Fallen London.

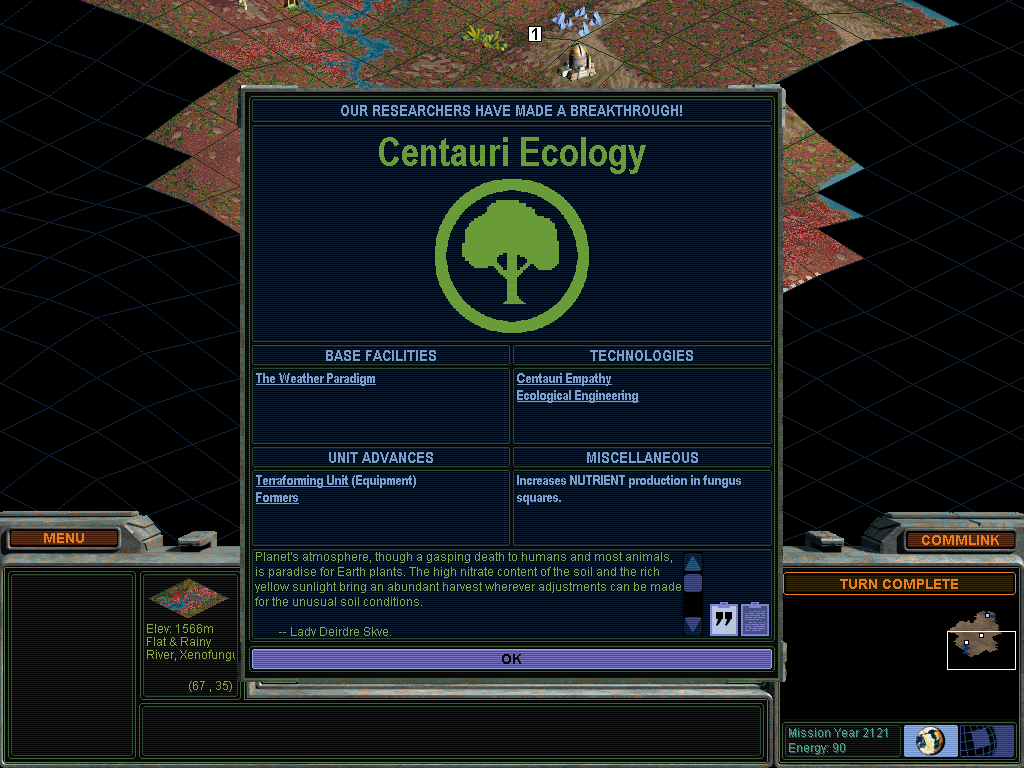

Or if you talk to Brian Reynolds, designer of Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri: "You know who else did an absolutely unbelievably amazingly wonderful job of flavour text? Ken Levine in the BioShock series. Those little tapes you play, the brilliant thing is you pick them up and hit play and they start saying their thing and you might be picking up loot or fighting and they're going on with their Ayn Randian philosophy! It perfectly builds that world."

"Resources exist to be consumed. And consumed they will be, if not by this generation then by some future. By what right does this forgotten future seek to deny us our birthright? None I say! Let us take what is ours, chew and eat our fill."—CEO Nwabudike Morgan

Industrial Base, a technology from Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri which unlocks The Merchant Exchange secret project and stronger armour

That's Reynolds' favourite piece of flavour text from Alpha Centauri, in which it's delivered when new technologies are discovered. He wrote about half of them and they were his idea, a response to solving an issue that came up with game's first prototype. His bid to transmute Civilization to settlers on Mars was feeling dry and lifeless, and he realised it was because Mars lacked the cultural touchstones that gave Civilization's players an intuitive understanding of the game, from what it meant to discover the wheel to what Ghandi was about. In Alpha Centauri, you'd discover Nonlinear Mathematics and you wouldn't know that it lead to a bigger laser gun.

Reynolds realised that he might be able to hint at Alpha Centauri's world through text, and he began to read sci-fi and look back to his philosophy degree, thinking about how the game might develop its roster of playable characters so players could understand their stances on the world, and how it might express its themes about the meaning of life. "Science fiction creates gripping worlds that you want to read about, so what's the essence of that, and how could I get it into my game?" he wondered.

The answer came in the quotations Frank Herbert scattered through his classic Dune series, fragments of imaginary texts which fleshed out groups such as the shadowy Bene Gesserit. "What I liked was that in one or two sentences he would sketch a whole chunk of his universe that wasn't the stuff that was explicitly gone into detail in the actual text. It was showing these other forces and philosophies, or cast new lights on existing characters. I turned out to be reasonably good at making up these little chunks and building a world that way. It was a great way to flesh out a world, a social world with characters and conflicts."

"Give a man a fish, and you can feed him for a day. But give a fish a man, and you can feed it for a month."

Song of the Sirens, a fishing rod from Path of Exile which raises the quantity and rarity of caught fish

'Embedded story'

For Dark Souls, flavour text also sketches out the world, and it also provides players with a game within the game. Director Hidetaka Miyazaki speaks about his philosophy of world building as creating an 'embedded story', in the sense that it encourages players to discover and make their own experience, and much of that discovery lies in interpreting flavour text.

"It's an interesting way of delivering extra gameplay to people who want more," says Ian Milton-Polley, who works with Morris at Frognation to translate the Souls series into English. "Of course those games can be played through without reading a single description, but part of the fun is digging into them and finding out the links between the figures who are mentioned, or watching four-hour YouTube series of other people who do it."

"For serious players, once they realise it's not lazily written and is a world being elucidated through the flavour text, it's a fun way to go through the game," says Morris. "It's for the core fans, the serious fans. There are different ways of giving a game more lastability, but the lore is very strong point."

"The ambiguity also serves up avenues for expansion in DLC, because the story is kept very close to the chest," says Milton-Polley. "You figure out most of it through interpretation and clues, and there's lots of scope for going back through the game and drawing out more from this and that. By not going into specifics there's a lot more leeway to expand."

"This amulet is said to have belonged to Fulvano. He was a man much taken with mild superstitions, and this talisman, he said, was a source of luck. It also served more sentimental purpose, for it depicts one of the great ships commonly seen at the docks of his homeland."

Fulvano's Amulet, an item from Pillars of Eternity which raises the reflex stat and grants a healing bonus

Dark Souls isn't the only game to use flavour text to build and bind its world. Pillars of Eternity links items and characters, too, introducing the story of an ill-fated explorer called Fulvano through boots, gloves and an amulet found on corpses in different locations in the world, and then builds it out with his letters found elsewhere. Pulling the player through the world, they invite questions: how did they end up where they did?

Flavour text isn't always about incidental stuff, however. Sometimes it has to support items which perform specific functions. Dark Souls, for example, has items which manage its multiplayer features, and their flavour text has to maintain the game's dreamlike ambiguity while giving the right level of hinting at what they do. The White Sign Soapstone, which summons co-op players, is explicit because it's so important to the game, but the Dried Finger isn't, because it's for hardcore players.

"Dried finger with multiple knuckles. Shrivelled but still warm. With this many knuckles, surely it cannot belong to anything human."

Dried Finger, an item from Dark Souls which re-opens the player's world to PvP invasions by resetting the invasion timer

"We write them so they fit into the world, but those are the ones you have to be careful with the language because you don't want to break the continuity of the story," says Morris. "I know Miyazaki is very conscious of reining in the functionality of the game and pulling it into the story. He has definitely emphasised the immersion and with multiplayer and the way players are brought in and out of the game, he's made an effort not to involve menus and lobbies. Anything that feels gamey he tries to downplay and hide it inside a seamless narrative."

The thing with flavour text, however, is that though it's about words it faces technical limits. But with limits come creative opportunities.

"Unclothed, origin unknown.

Has nothing to fight with,

but life-affirming flesh."

The Deprived class from Dark Souls 2

"I just like the suggestiveness of mere flesh being a life-affirming thing in and of itself in the entropic world of the Souls games," says Milton-Polley. "Also, I remember the character limits were severe, and so these class descriptions all ended up sounding a bit like miniature poems, which turned out quite nice, in my opinion."

The upside of limitations

A major challenge for translating from Japanese to English is that kanji is much more compact than English. But all writers face the struggle of fitting all they want into the space available. One of Kennedy's intentions for Cultist Simulator was that its snippets of flavour text would be 25% shorter than the equivalents in Sunless Sea and Fallen London.

"Over time, the expectations of what the writers could put in the boxes crept up," he says, explaining that it led to players starting to feeling short-changed when they encountered shorter ones, and discouraging the writers from being disciplined with their text.

"As a games writer you have the player's attention for an instant between the interactions of the game, and the moment you lose it you're giving them homework and they skim. For years we tried to find ways of forcing players to read, and we realised there's no point. If you're interested in the text, you'll read it."

Reynolds' answer to this in Alpha Centauri was to voice the text, having actors read it out over the top of play so it didn't interrupt players. "It should seep in by osmosis, minimise the amount you take the player away from the gameplay," he says, and in Alpha Centauri it works well, but back then, he was able to record all of its dialogue for $50,000, an extraordinarily low budget by the standards of today.

"This garish amulet, once worn by an over large imp, makes time an insignificant thing."

The Flavor of Time, a legendary amulet from from Diablo 3 which raises movement speed and reduces cooldowns

And besides that, most flavour text is a quiet addition to play. It's there to be discovered and enjoyed at a different pace to the rest of the game, on the player's terms and perhaps not even when the game is running. "For me personally, what I really enjoy about flavour text is that it's an extension of the game into your own time," says Milton-Polley. "I like to get into nitty gritty of universes. It's a fun space for my mind to inhabit when I'm not playing the game."