Super Meat Boy Forever is an auto-runner, but it might be the best auto-runner

Plus, what Tesla stock and diabetes have to do with platforming enemies.

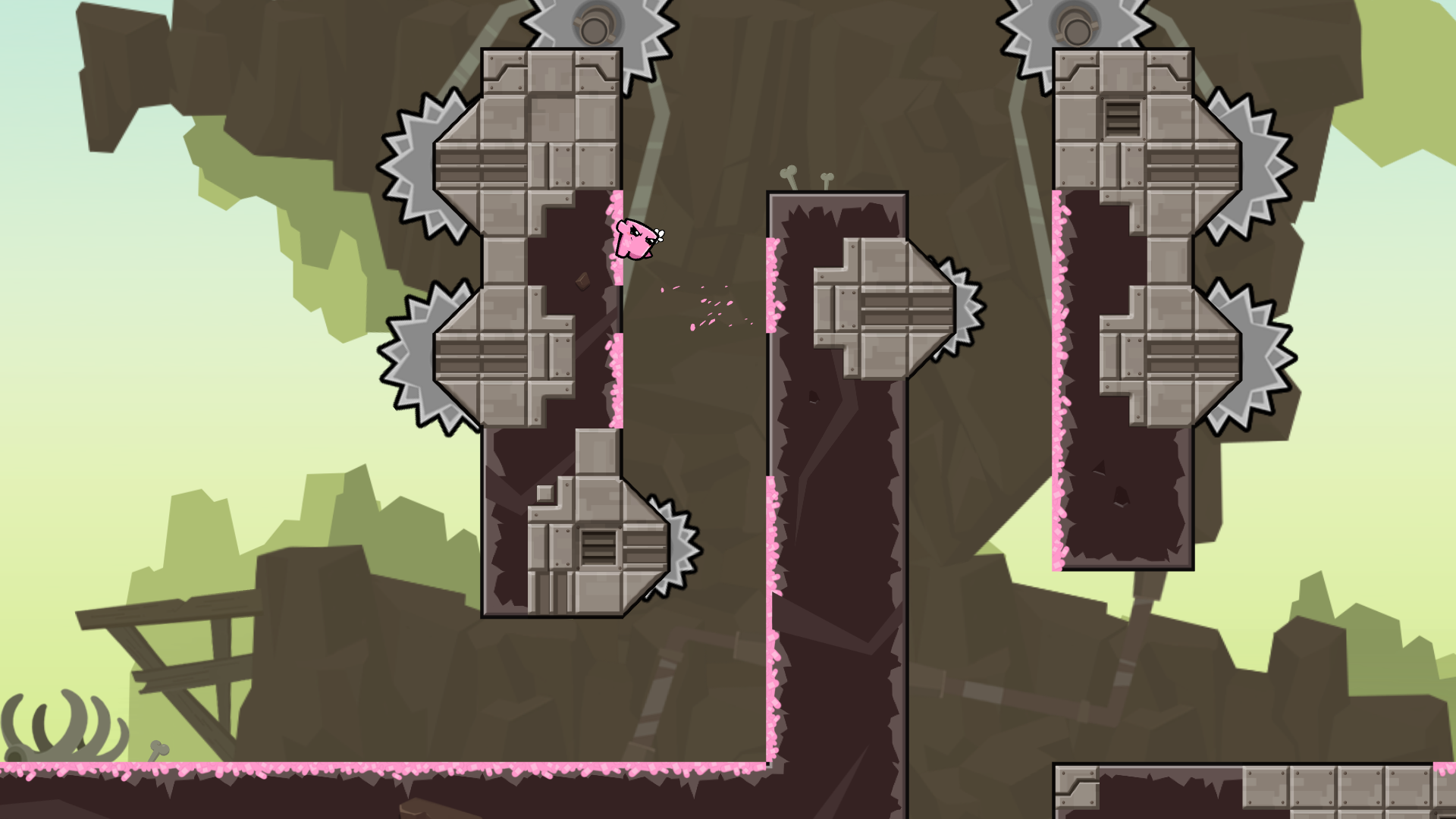

My first look at Super Meat Boy Forever was its trailer, beneath which commenters lament that it's an auto-runner—a sidescrolling platformer in which the character is always moving left or right regardless of input. It's a style of associated with "simplified" mobile games, and for some people that's an instant strike. Having played Super Meat Boy Forever at PAX East yesterday, I am certain that automatically moving left or right does not make it bad. The dozen or so levels I played were fantastic. I learned a lot. I died a lot. And I didn't miss old-style Super Meat Boy. I felt like it was back, rejuvenated after a productive slumber.

I wasn't thinking, 'Aw, an auto-runner?' I was thinking that SMBF could be the best auto-runner I've played.

The anti-auto-runner crowd may feel vindicated or dismayed to know that Super Meat Boy Forever did in fact start as a concept for a mobile game. "Super Meat Boy came out in 2010 and around that time everybody's losing their mind with iPhone stuff, and Meat Boy was popular, so everybody would ask, 'When's it coming to Android, when's it coming to this or when's it coming to that,'" designer Tommy Refenes tells me as I struggle with a level. "And I was thinking, 'Why would you want that game? A twitch platformer with precision controls on your [iPhone]?' … It took me a lot longer that it should've to realize that it's not that they wanted that game, it's that they wanted a game that's hard, controls well, and feels like Meat Boy in a mobile form. So that was 2011, and I prototyped a one-button Meat Boy in a GDC hotel room, and I saw it had potential."

That prototype sat around for a few years before development on Super Meat Boy Forever began in 2014. Team Meat worked on it for three months, and then work stalled. Last year, which is when we learned that Edmund McMillen had left Team Meat, Refenes picked that prototype back up and saw its potential again.

"At its core, Meat Boy is all movement—movement through levels that compliment the movement … they're symbiotic," he says. "And I liked the idea of stripping out a whole bunch of control and seeing what we can do with something simpler, and the unintended side effect of it is it's a difficult game, but it's still very accessible. I've had more people able to play this game than Meat Boy will potentially ever have. My wife, for instance: she played through the first one, but she hated that it hurt her thumbs—she hated having to hold down the run."

Refenes says he even beat a world with one hand. I could definitely not do that. Super Meat Boy Forever is still hard. By imposing new limitations—the auto-running, the two button control scheme, doubled from the prototype's one button—Refenes gets to introduce new skills to master and new ways for me to screw up and explode in a shower of meat. One button jumps and punches (or kicks, if you're playing as Bandage Girl) mid-air, extending the length of a jump. The other punches downward diagonally, or squishes Meat Boy down to slide under banks of saw blades.

Perfect, gentle hops to glide between blades are still a thing, but so are quick smashes into the ground, timed slides and leaps, and super long jumps, which can be extended by catching an enemy with a punch, which allows another punch before landing.

Enemies are essentially platforms that kill you if you screw up. The Betus, which returns from SMB, is Refenes' favorite. It's a floating blob-thing inspired by his experiences living with diabetes. "I bought Tesla stock at 17 dollars a share, like almost at the IPO, and my blood sugar was low one day because I'm diabetic, and I sold all of it while my blood sugar was low," says Refenes. "I sold at like 30 [dollars], so I made money, but it wasn't the best decision I've made. So the lore behind the Betus guys is their blood sugar is low, so they eat Meat Boy, and Meat Boy has no carbohydrates so their blood sugar can't come up, so the Betus are confused and walk right into death."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

As he's talking, I learn not to mash the punch button after being swallowed, but to hit it exactly three times to burst out of a Betus so I don't waste my mid-air punch, which I need later to clear a saw blade. I learned a lot while Refenes stood behind me stoically refusing to help. It wouldn't have been any fun if he were giving me hints. Just like the original game, the joy of Super Meat Boy Forever is dying the same way five times, thinking, 'OK, for fuck's sake, I obviously need to try something else' and then figuring out what that something else is with another 10 (or more) deaths.

Animation in SMBF is far smoother and more expressive than SMB's, which Refenes says is the difference between having zero budget and the budget to hire Adult Swim artists.

One segment that gave me a lot of trouble: leap to the right over a giant saw blade; it starts rolling; leap off a wall back over the blade, hop up to a dissolving platform and wait until the blade passes below and cuts through a wooden blockage; fall through the hole it created and slide down the wall; leap to the other side of a large chamber (remember to punch!) before being sliced up by another saw blade; narrowly avoid a platform that'll just send you into another bank of blades; fall to a passage below and very narrowly squeak into it while jamming the down button to slide beneath yet more sawblades.

That one took me a few tries. And I wasn't thinking, 'Aw, an auto-runner?' I was thinking that SMBF could be the best auto-runner I've played.

It's different than Super Meat Boy, but that essence remains in all the ways that are important. What made the brutally hard feats of leaping non-frustrating in SMB, for instance, were the small levels and instant resets, which SMBF maintains. Being an auto-runner means it needs more space to auto-run in, but levels are divided into numerous checkpoints, each containing a manageable set of challenges.

Because it wasn't in the demo I played, I was worried that Refenes had decided to scrap the end-of-level replays from SMB that mashed all your failed attempts together so you could admire every failure and every breakthrough on your way to completing a level. Nope, they'll be there, they're just taking a while to develop on account of the increased complexity. Because levels are now much longer, and there are multiple reset points, those layered replays should be absolute sagas once Refenes figures out how to implement them.

SMBF is coming to PC (and consoles and phones) before the end of the year—hopefully before the birth of his first child, says Refenes, a comment that happened to come as the villain, a fetus in a tank, kicked a baby. He laughed at the irony while pointing out that animation in SMBF is far smoother and more expressive than SMB's, which he says is the difference between having zero budget and the budget to hire Adult Swim artists. It shows, especially in a brief cutscene he played for me on his phone, in which the villain smashes through a forest in a ridiculous tank.

The silly story isn't too important, though. All I cared about was that the brutal, but almost magically non-frustrating, platforming of SMB had been retained. Based on what I played, it's all still there. If Refenes said he had 10 more levels for me to play, I might have asked him to pass me a spare exhibitor badge so I could hide out in the convention center a little past closing.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.