Let's get this out of the way first. G String is a terrible title and I've absolutely no idea why this game is called that. It's also far from the wildest thing about this total conversion mod which, as of this month, did a Black Mesa and launched as an official, priced Steam release. That would be the fact G String is (almost) entirely the work of a single person, developed over a whopping twelve years. This is important to bear in mind, partly when considering G String's shortcomings, but mainly because it is one of the most ambitious Source-based shooters I've ever encountered.

G String is a full-on singleplayer FPS experienced across fifteen distinct chapters, amounting to a campaign that's a fair chunk longer than Half-Life 2. It puts you in the role of Myo Hyori, a teenage girl and genetically-enhanced super-soldier who escapes from her biopod after the facility holding her captive is struck by falling space debris. From here, she embarks upon a violent dash across G String's North-American megacity, as various factions try to kill her, capture her, or otherwise use her for their own ends.

The story is told in the Half-Life model. While there are establishing cutscenes between each chapter, Myo is a silent protagonist and her motives are never made entirely clear. She may be trying to escape, hell-bent on revenge, seeking justice for the city's downtrodden, or a combination of all three. Alongside the more obvious nods to cyberpunk fiction like Ghost in the Shell and Blade Runner, the developer Eya Eyaura cites David Lynch as another major inspiration, which comes across in the narrative ambiguity, as well as surrealist sections where Myo seems to be chasing after a strange, fleshy blob.

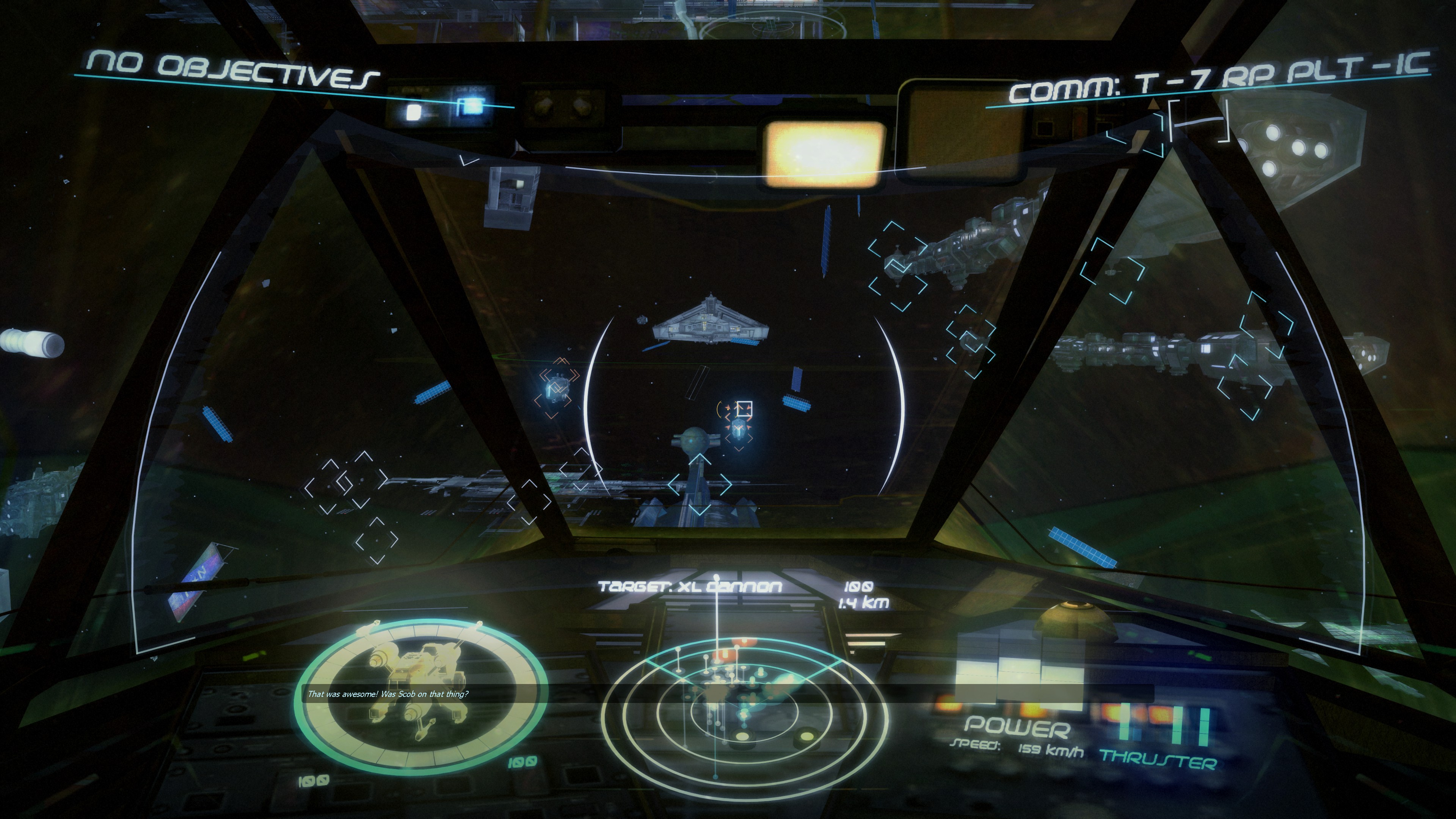

As with Half-Life 2, it's G String's city that functions both as narrator and main character, with each chapter taking you through a different area of the city. An early chapter sees you exploring a robot ghetto run by a wargaming AI known as LOG-9. Another sees you slowly ascending a giant, Blade-Runner style techno-pyramid that serves as the city's main provider of breathable air. Several chapters take you off Earth entirely, first in a giant transport ship, and then later in a low-orbit space-battle, complete with your own space fighter.

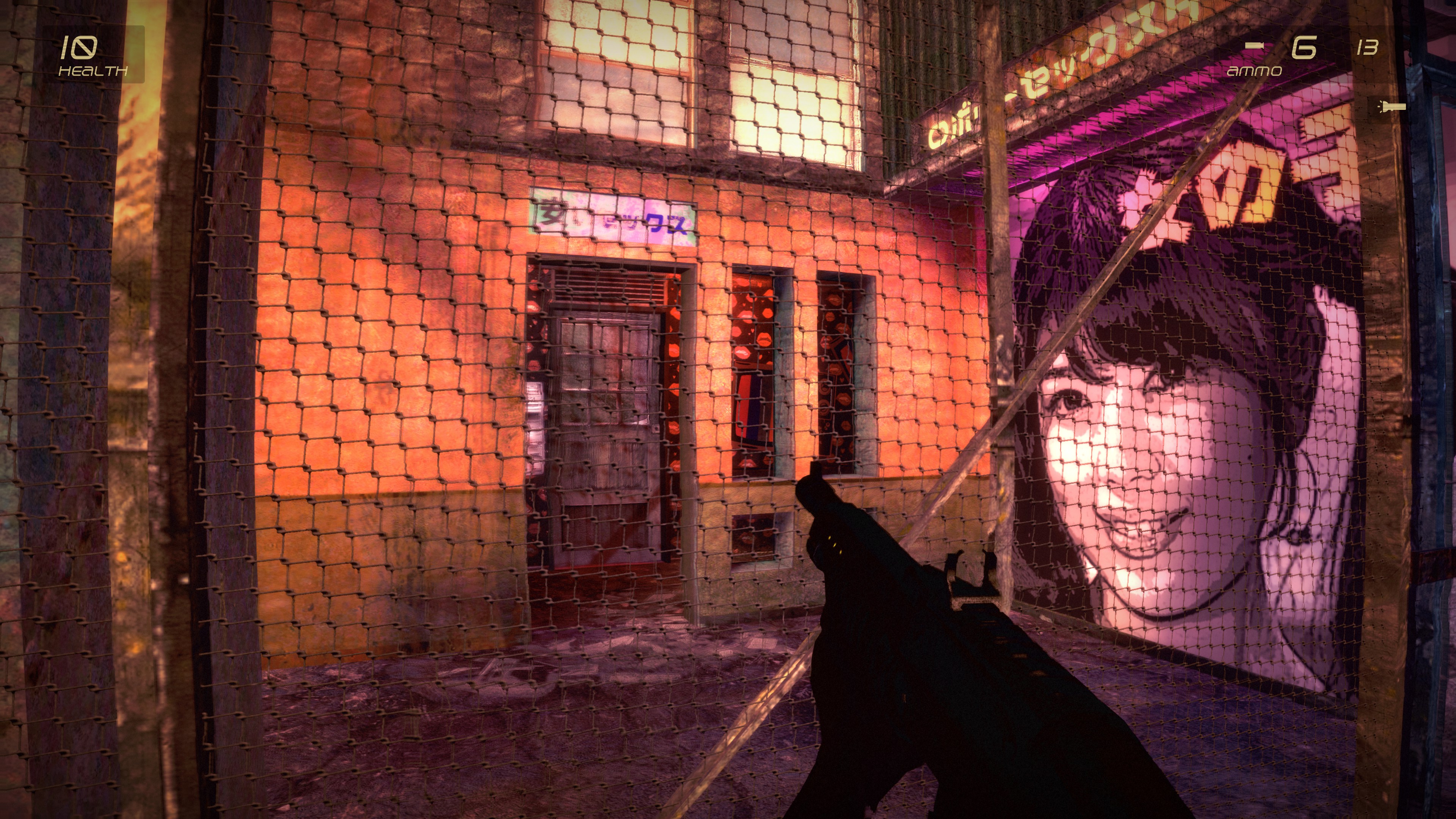

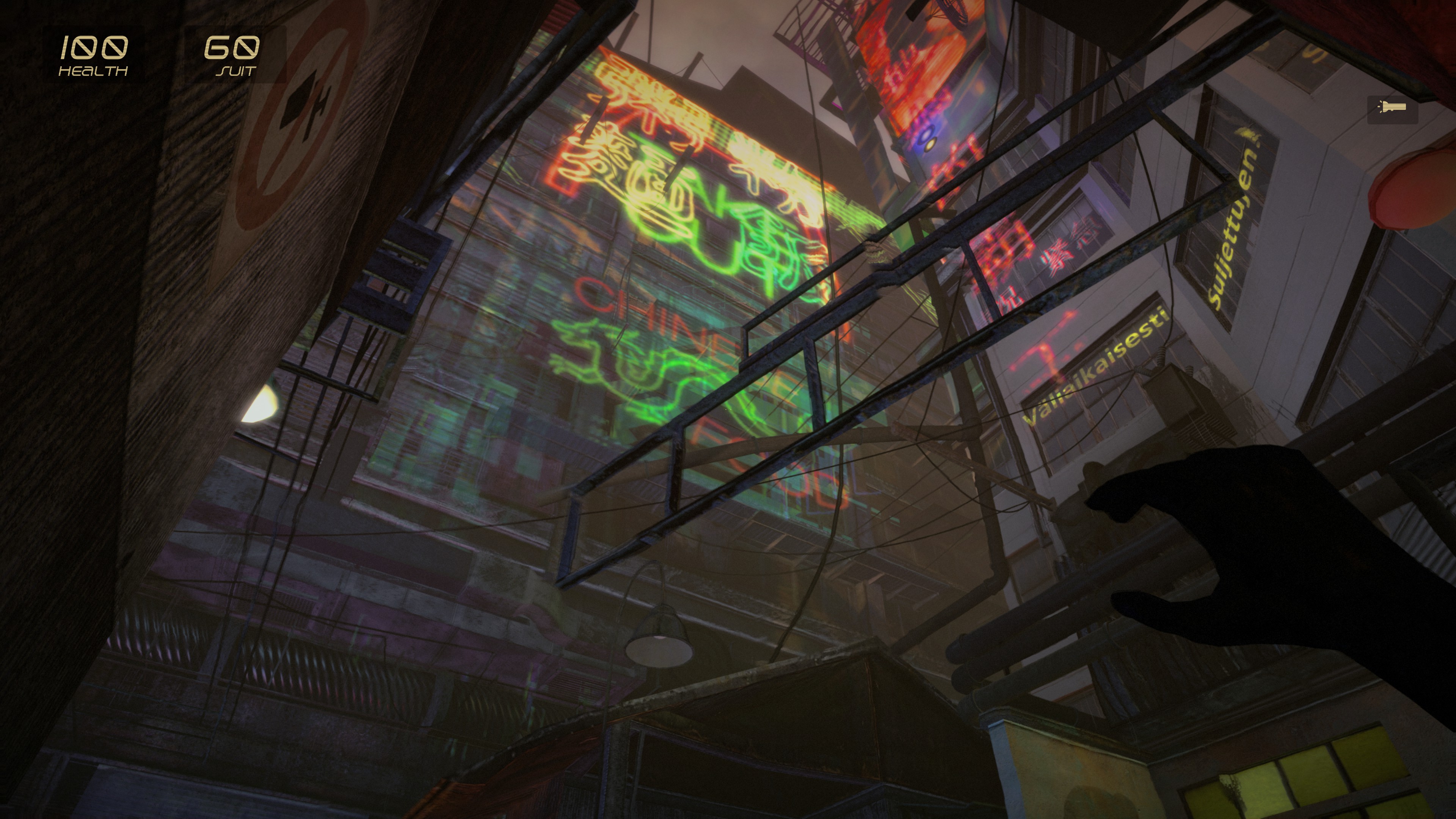

At its best, G String is utterly captivating. The Source engine may look dated, but G String nonetheless manages to create some truly breath-taking imagery. The use of neon holograms and hi-res photographs on billboards and buildings add considerable detail to the Source engine's sparse geometry. Eyaura also has an eye for what Source is good at, namely complex and organic-feeling representations of industry and urbanisation. You'll often see gargantuan structures stretching off into the distance, their supports and foundations silhouetted against bright lights. It makes these buildings seem incomprehensibly large.

G String frequently paints an impressive picture, but it's rarely a pretty one. Its cyberpunk society isn't merely oppressive and dysfunctional, but in a visible state of collapse. When it isn't being accidentally bombarded by falling satellites and space junk, it's being deliberately bombarded as retribution for attacks by rebel factions. During the campaign, the city is also struck by both an earthquake and a hurricane, courtesy of the Earth's monstrously altered climate.

Indeed, G String often feels more like survival horror than FPS. Its residential areas are palpably squalid. No amount of neon billboards can conceal the appalling levels of decay and destitution, the densely graffitied walls, the soiled furniture, the scattered remains of rotting robots. G String has a thing for horrible robots. One of the most common enemies is a twitching, shuffling Geisha serving-bot that is possibly the most disturbing thing I've ever seen. It isn't particularly dangerous, but I'd rather face a dozen of the game's heavily armed NATO Terra soldiers than be stuck in a small room with one of those scuttling nightmares.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

G String hits a lot of the typical cyberpunk tropes, from satirical radio announcements about voluntary euthanasia to patently absurd advertisements for services like boosting your pet's brain power. And like the underwear garment after which it is named, G String has a grotty side to it. Another common enemy is a sex-robot that moans when killed, while you'll frequently encounter vending machines that dispense women's dirty underwear.

Indeed, the gender and sexual politics of G String merit deeper discussion. The world it presents to you is explicitly misogynist. Men run the show, all the human enemies you encounter are male, and most of the women you see are plastered on billboards. Yet these explicit problems are implicitly criticised. The sexual elements come across as revolting rather than titillating (the sex robots, like the Geisha robots, are deeply unsettling,) while the handful of female characters you physically encounter are all members of resistance groups. It's also no accident that the protagonist is female, tearing through this aggressive and domineering society like a petrol station sandwich through a lower intestine, all while the three male antagonists scramble not to kill her, but to repossess what they perceive as a valuable asset.

All this feeds into G String's primary theme of dehumanisation, the consequences of hyper-capitalism on an individual's right to life. This is something the game does really well. Human detritus is everywhere: corpses, twitching android torsos, people with half their limbs replaced by cheap robotic prosthetics curled up on soiled mattresses, struggling to breathe the toxic air. This stark expression of societal and individual decay is what makes G String stand out from the cyberpunk crowd. The atmosphere is one of cloying tension, and there were times when G String's eeriness genuinely unnerved me. It could be the noise of a shrieking baby behind the rotting wall of an apartment, or encountering a horrific slug-like enemy that lurks in the game's storm drains.

In play, G String is basically a less-polished version of Half-Life 2. The weapons are all remodelled versions of Half-Life equivalents—pistols, shotguns, grenades etc. There are a couple of standouts, like the plasma spitting "wave rifle" and the ridiculously powerful "Kobi Gun," but the game could have done with a few more weapons to compensate for its additional length. Combat emphasis is very much on shooting first, second and third, else any enemy with a half-decent weapon will cut down your health bar like it was the Amazon rainforest. This, combined with the fact that the game likes to wrong-foot you with enemy placements, means that death is frequent, and can feel cheap.

In play, G String is basically a less-polished version of Half-Life 2.

Fighting isn't always mandatory. It's often possible to avoid direct engagement of enemies, either sneaking past them or simply running away. Indeed, G String is as much about navigational puzzling as it is shooting—another mark in the survival horror column for the game. It also features a mechanic whereby killing enemies results in a greater number of enemies populating later areas. It's hard to judge how functional this system is, but there were certainly moments where I'd seemingly clear a room of enemies only for another wave to pour in.

I like G String a lot. But don't come in expecting the same levels of refinement as Black Mesa. The voice acting ranges from surprisingly good to village pantomime, while enemy ragdolls bear a tenuous relationship with gravity (and their own limbs). The biggest problem is that G String's ambition sometimes gets the better of it. There's too much of everything, too many awkward platforming sections, too many 'the floor is lava' bits, where you need to hop across tiny scraps of junk to avoid falling in toxic sludge, too many annoyingly placed turrets that slice off half your health bar when you step into a room. Worst of all, there are too many vents that you need to crawl through agonisingly slowly. Seriously, the game's pacing would be significantly improved if the developer simply increased the crawl speed.

There were times when G String tested my patience. But just as my finger was hovering over the escape button, suddenly you'd be climbing the giant pyramid from Blade Runner, or fighting your way through a besieged transport ship in zero gravity. It's a game of intense extremes, and its huge variety and distinctive atmosphere makes it worth persisting through even in its weakest moments. Having one good Source engine shooter in 2020 was enough of a surprise. Now there are two.

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.