Returning to Dead Space

Looking back on a classic.

Reinstall invites you to join us in revisiting PC gaming days gone by. Today, Andy goes out on a limb to reexamine Dead Space.

There were 1,332 crew members on the USG Ishimura, but it took an unassuming engineer with a power tool to defeat the ungodly evil that devastated their ship. Isaac Clarke (see what they did there?) is the unlikely hero of Dead Space, an atmospheric space horror game that came out of nowhere at the end of 2008.

After losing contact with the Ishimura, a massive ‘planet cracker’ mining ship, the owners send a small team—of which Clarke is a member—to find out what happened. When they get there the ship seems abandoned and its lights are mysteriously out, so they go aboard to investigate. Bad idea.

There’s nothing that unique about Dead Space. Its mix of cold, industrial sci-fi and gruesome bio-horror has been done many times before, from Alien to System Shock. But it makes up for a lack of original ideas by just being really good.

Borrowing heavily from Shinji Mikami’s peerless Resident Evil 4, it’s an over-the-shoulder shooter that blends slow, atmospheric horror with bloody action. You can trace almost every moment back to a film, but it’s so fun, so atmospheric, and so well-designed that it doesn’t matter. It’s a loving homage to classic horror and sci-fi cinema.

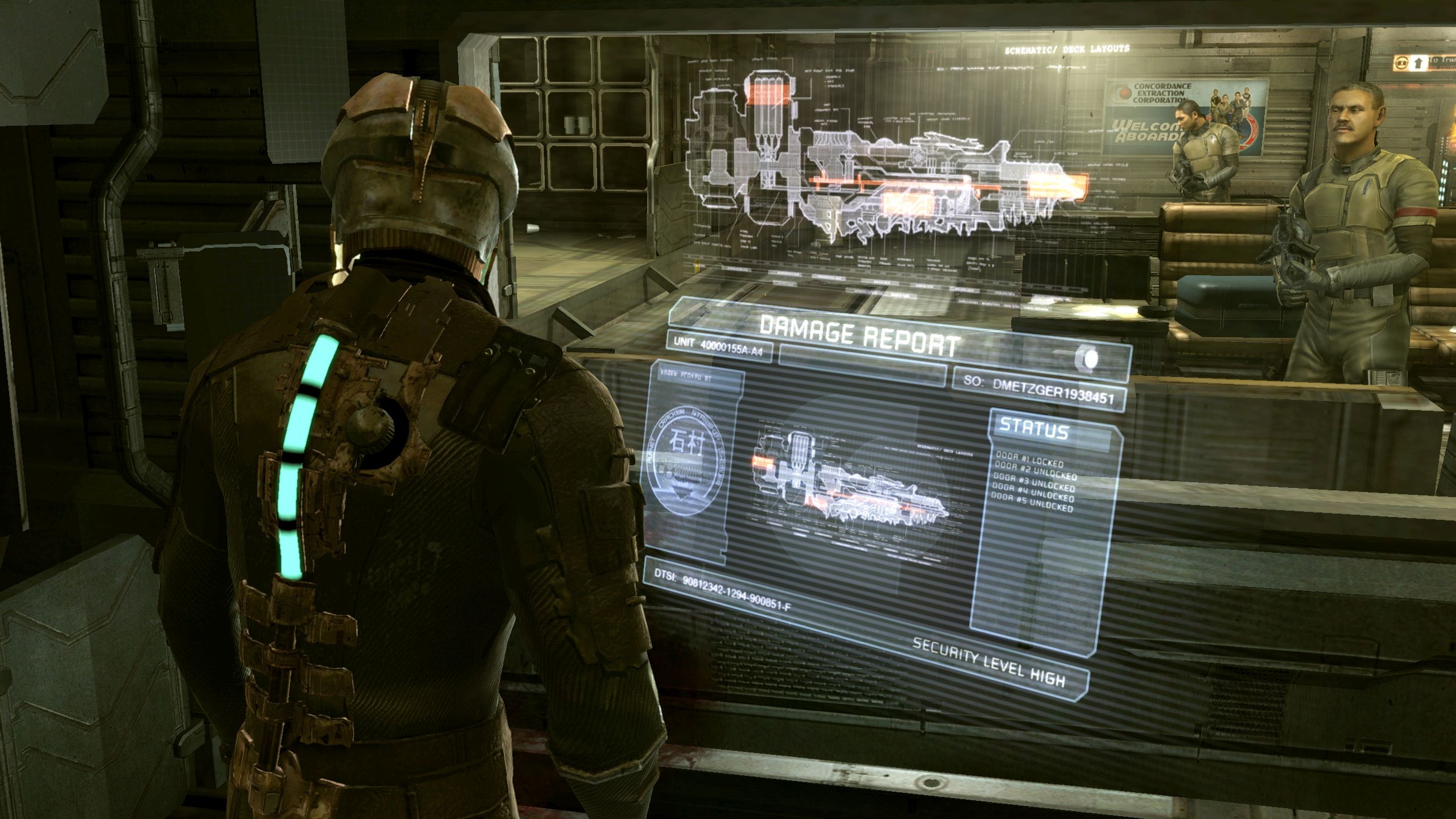

Playing it now, years later, I’m amazed at how good it looks. A few blurry textures and low-poly character models aside, the Ishimura is still a wonderfully atmospheric environment. It’s a claustrophobic warren of oppressive metal corridors that owes a lot to Alien’s USCSS Nostromo. The single setting is one of its greatest strengths, giving the developers the chance to really flesh it out. It feels like a real, lived-in place that was once teeming with people, which makes its current abandoned state even more eerie.

You move through different areas—engineering, medical, the crew quarters—and in this sense it’s reminiscent of BioShock’s Rapture, revealing more about the place and its former inhabitants as you delve deeper into it.

The Ishimura has a lot of dark secrets to be discovered, chiefly its ties to Unitology: a fairly obvious Scientology spoof that would come to form the backbone of the series’ mythology over the two sequels. There’s a reason why the crew are all dead and the ship is swarming with monstrous creatures, and a desire to find out keeps you engaged.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The enemies, called necromorphs, are straight out of the Stan Winston book of creature design—John Carpenter’s brooding ‘80s horror classic The Thing is a clear inspiration. To design them, Visceral’s artists studied photos of car crash victims and war casualties.

Compared to, say, the genuinely unsettling denizens of Silent Hill, they do look fairly ridiculous. They’re bloody constructions of squished-together body parts that flail and screech as they predictably burst out of vents. But in the heat of the moment, with five of them bearing down on you, pincers swinging, they’re an effective foe.

Dead Space isn’t that scary. It falls into the Resident Evil camp of horror games, with cheap jump scares and tension-building looming large in its vocabulary. It won’t affect you on some deep, psychological level, and it won’t tease out deep-seated primal fears. It’s more like a ghost train, with people in white sheets popping up and going “Boo!” But that’s fine, because the game has no pretensions otherwise. Never knowing when a necromorph is going to come bursting through a door or out of shadowy corner is what keeps the tension taut and constant.

To defeat these creatures, you have to take advantage of the game’s ‘strategic dismemberment’ gimmick. You can’t kill a necromorph just by blasting at it with the game’s array of deadly engineering tools—you have to sever its limbs.

The game teaches you this by having the words "CUT OFF THEIR LIMBS" scrawled on a wall in blood. Then it tells you in a tutorial. Then an audio diary. Then another tutorial. Subtlety is not really the game’s strong point. There are a few quieter, more thickly atmospheric moments, which sadly fall by the wayside as the game gets increasingly louder and more action-packed: a crescendo that kept on going until the end of the underwhelming Dead Space 3.

The score, although largely forgettable, makes use of Krzysztof Penderecki-style timpani rolls and sharp, piercing strings to build the suspense, a ploy straight out of Kubrick’s The Shining. Visceral watched hours of horror films during the game’s development to get ideas for scares. Cult scary sci-fi flick Event Horizon is another obvious influence, with a story, locations, and monster designs so similar, it almost feels like an adaptation at times.

This is a game that’s quite unashamedly steeped in imagery and sounds from the silver screen. As a result it can feel overly imitative, but a few visual elements—particularly the green glow of Isaac’s clunky helmet and the Unitology stuff—are distinctly its own creation.

PC gamers were short-changed with the port, and you’ll need to tweak a few things to get it running satisfactorily on modern machines. Disabling vsync on modern GPUs causes certain events not to trigger, making progress impossible. But with it enabled, the game feels unplayably slow and clunky. You have to disable it in-game, then enable it through your graphics card control panel to fix this.

There’s also appalling mouse/controller lag on some PCs. But wrestle with this stuff successfully and you’ll discover an enjoyable horror romp with a memorable setting and great set-pieces.

In moving away from a single, focused setting and introducing more third-person shooting, the sequels never really recaptured the magic of the first game. Hopefully the next will take a step back and be another smaller, slower game like the first. Alien: Isolation is proof that bigger and louder isn’t always better.

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.