Blue light isn't ruining your eyes, but you may want to reduce your exposure anyway

Is the danger of blue light overhyped? We asked a doctor.

In 2020, MSI announced the PRO MP242 series of "eye care monitors", with "low blue light and flicker-free technology". I'd seen software and prescription lenses promising to cut down on blue-light exposure, but this was the first time I'd seen a computer monitor come with the feature built in. I asked an MSI rep why this had become a selling point—what is the actual danger of blue-light exposure?

Health Kit is PC Gamer's coverage of health, ergonomics, and wellness.

What should I do if I have wrist pain?

Nootropics marketed to esports viewers aren't necessarily safe

How to sit at a desk with good posture

5 ways to avoid hurting yourself while PC gaming

"Prolonged exposure could affect our vision by prematurely aging the eye and even cause retina damage which leads to macular degeneration," they said. "Also, as one of the shortest, yet highest energy wavelengths in the light spectrum, blue light flickers easier and longer than other types of weaker wavelengths. This flickering leads to eye strain and subsequently, further eye and vision damage."

That sounds scary, but of course a company selling low-blue-light monitors would make blue light sound dangerous. And I had to wonder: If the short, high-energy wavelength of blue light is so bad for our eyes, why aren't our eyes already damaged? The sky is blue and it shines blue light at us daily.

I asked a doctor. Dr Lindsey Migliore, also known as Gamer Doc on Twitter, is an expert in health issues that affect people who play videogames. Like the MSI rep I spoke to, Dr Migliore noted that blue light has the shortest wavelength on the visible spectrum, and the highest energy. "In large doses," she said, "this can cause damage to a multitude of cells in the eye. The good news? Computer and phone screens don't produce anywhere near this level of light."

Perhaps we shouldn't over-worry about eye damage, then, although Dr Migliore added that we don't know for sure how screen use "may well impact our eyes in the long run" or if there are different effects on children. Even so, there are other reasons to care about blue light.

"The true risk of blue light is how it can disrupt our sleep/wake cycle, known as the circadian rhythm," Dr Migliore said. "During the day, exposure to light improves attention and mood. At night, blue light suppresses the release of the hormone that tells your brain it is time for bed: melatonin. This makes it harder to fall asleep, decreases the quality of sleep, and leads to more awakenings."

Along with sleep disruption, "some studies even suggest that blue light exposure at night may increase your risk of depression, diabetes, and heart disease," said Dr Migliore.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The theory goes that our brains evolved to react to daylight with wakeful alertness, and to react to darkness with a flood of sleepytime chemicals we need to properly rest. But the LED screens we spend so much of our time looking at project a significant amount of blue light—present in light that looks white—at us. And if you're anything like me, before sleep you go from staring at a computer monitor playing Yakuza 0 to staring at your phone in bed.

This is 2021. Most of us rely on screens not only for work, but to wind down at night.

Dr Lindsey Migliore

How much of a problem is this? Talking to Time, neurologist Dr Cathy Goldstein expressed skepticism. "Blue light has become the gluten of the sleep world," she said. Just as gluten-free products, important for the roughly two percent of the population with coeliac disease, became a fad due to the broader public having only a vague understanding that gluten is a thing that's bad, products that promise to shield us from blue lights are everywhere now. Here's a blue-light skincare serum that'll set you back $150.

"Medical information will forever be sensationalized in both directions," Dr Migliore says. "Companies who stand to make a profit from trendy blue light glasses or gummy vitamins that claim to protect your eyes should never be the primary source of information. Whenever you hear a claim that's vaguely medical, think, 'does this person stand to profit from this detail?'. Blue light exposure should be minimized, but you don't need to spend excessive amounts of money to do so."

There are other reasons to think critically about how much we look at screens, too. "Staring at computer monitors for long periods interrupted can cause a multitude of other issues," Dr Migliore says. "The risks include eye strain, dry eyes, and a condition called accommodative spasm which results from your eyes being effectively stuck focusing on shorter distances." For that, she recommends following the 20/20/20 rule: "Every 20 minutes of screen time, take a 20 second break to look at a spot 20 feet away."

While some doctors recommend we give up on looking at screens entirely for the three hours before bedtime, those doctors have perhaps never been on a raid. "This is 2021. Most of us rely on screens not only for work, but to wind down at night," Dr Migliore says. "If you can spend the three hours before sleep meditating, reading a paperback, and recharging, go for it. However, for the rest of us, choosing prescription lenses with blue light filters or picking up a non-prescription pair of blue light glasses can cut down on our exposure. Put your phone in dark mode after the sun goes down, and try a blue light filtering application for your tablet or computer."

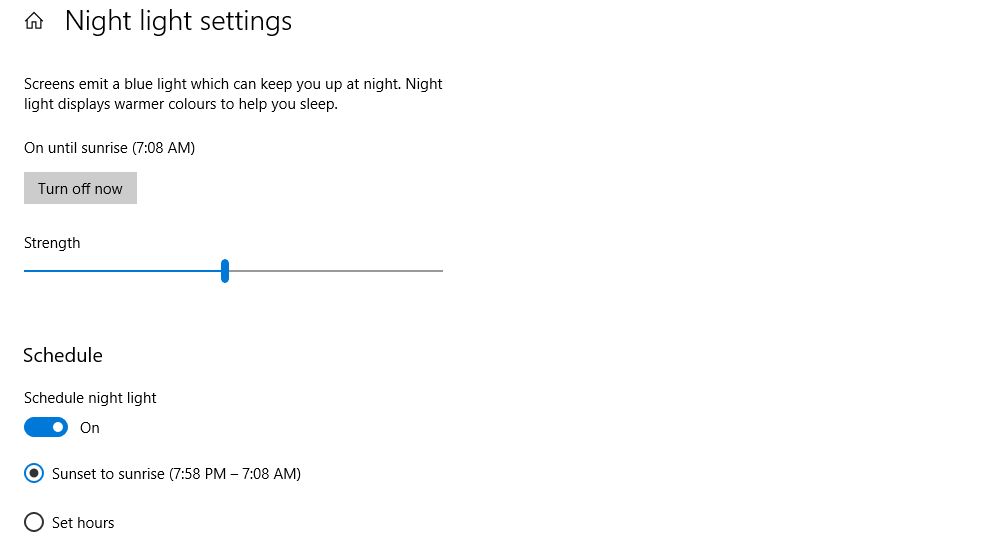

Windows 10 has a night light mode in Settings>System>Display, and f.lux is a free program that will alter the color of your monitor to suit the time of day. There are apps available to filter blue light on phones, and newer models may have one buried in the settings you've never noticed.

And if cutting down on blue light exposure doesn't help you sleep, Dr Migliore suggests the following: "Focus on exercise and nutrition. As little as 10 minutes a day of exercise can have profound effects on sleep quality. Stay hydrated, avoid caffeinated beverages after the sun goes down, and cut down on processed foods."

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.