35MM is a quiet tour of rural Russia after a deadly outbreak

Thoughts on a deeply flawed post-apocalypse tale with a ton of heart.

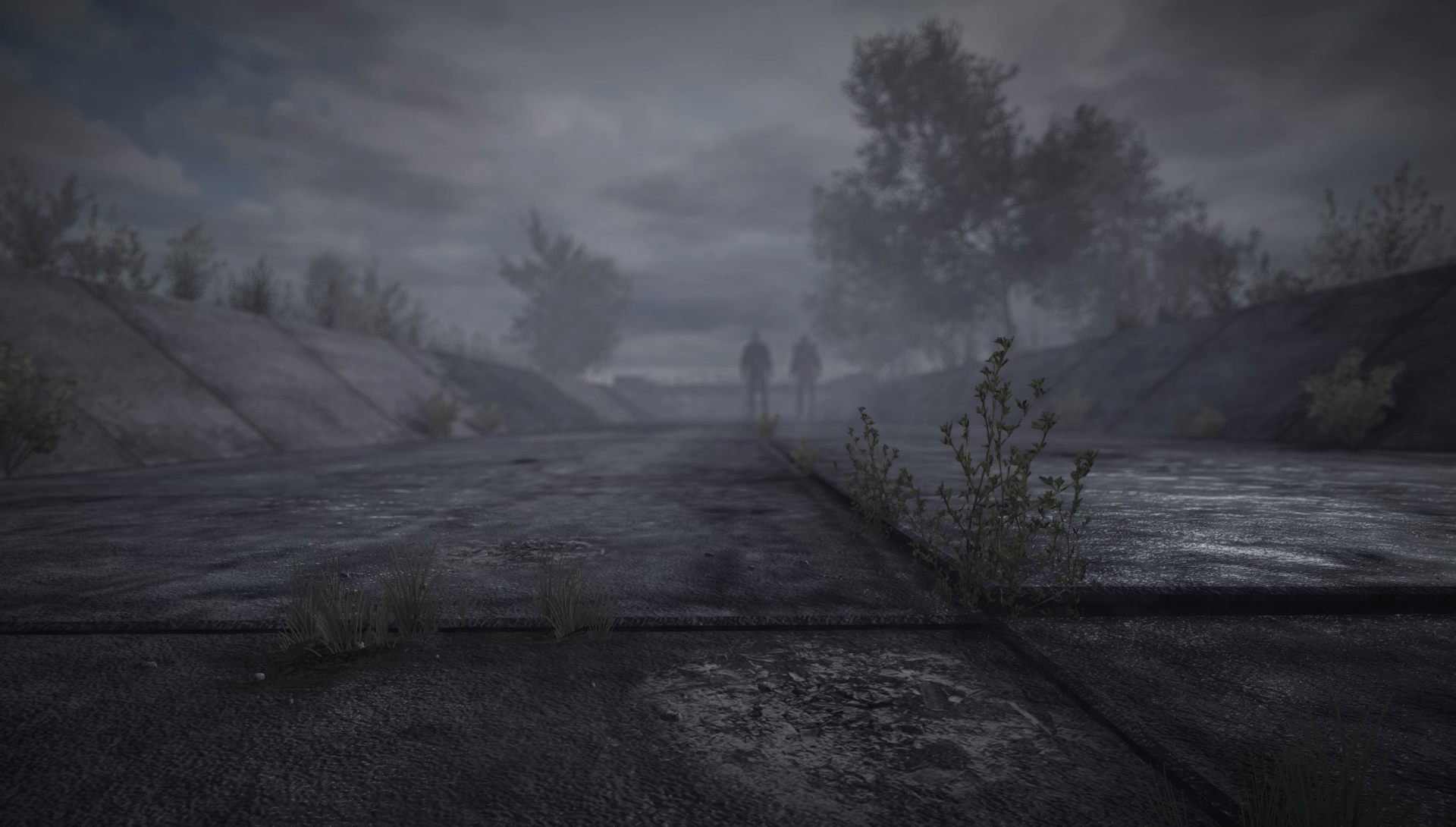

I spent most of the opening hour of 35MM walking through vast expanses of Russian wilderness, following rudimentary dirt roads, and only stopping to check the occasional jalopy husk or abandoned farmhouse. There wasn’t much to see. Empty beds, rusty cans, rotten wood—as it turns out, the post-apocalypse is pretty mundane.

35MM is a first-person adventure game in which you and an initially unnamed NPC partner traverse the Russian wilderness in order to fulfill a promise. I’m not exactly sure what that promise is yet (I’m about two hours in), but I’m not sure I care. The narrative is incredibly vague and comes across as secondary to the peaceful devastation that makes 35MM so entrancing despite its obvious flaws. Whenever it quits making weak stabs at storytelling or forcing me through its buggy action scenes, it lets me take pictures of an abandoned tractor or soak in the silence of a nice countryside walk. Those moments invigorated my spirit in surprising ways.

From Russia with uhh

The setting evokes a peaceful isolation: a ramshackle village in thin fog, the distant silhouette of a church. Traces of old fire pits dot the yards of every house, showing me how cold it is. It’s all wrapped up by a dense Russian forest in the subdued pastels of an impending winter—grey, yellow, and olive green. The emptiness is unnerving, but the silence is a relief from the regular hustle and bustle I expect from the town. I’m free to wander as I please, even if some of the doors won’t open until my partner—a walking, talking, event trigger—stands close enough.

First, he gets a fire going. I press ‘E’ and my character’s bum sticks to a small stool. I’m captive to a one man show, my partner’s poorly translated monologue of man’s downfall after the ‘outbreak’. I can barely make sense of the subtitles. When 35MM overtly tries to tell a story, it’s a mess.

The scene finishes, and I deduce I’m supposed to find some water in the village well. We’re going to boil it and fill our empty stomachs to stave off hunger. It’s past dark and the only items I can use are a camera and a short knife. If video games have taught me anything, things are about to get dangerously spooky.

Most of the homes are empty except for hollow food tins and lonely chairs. I keep expecting a monster to stumble out of the shadows. Up the road, I enter the abandoned church, and with a newfound lighter, I test the wick of an old candle next to a podium. It catches right away and gives off a faint glow, illuminating a few religious portraits on the wall. I’m not a believer, but this sure is a cozy light. I pull out my camera and take a few pictures. I want to remember this, in and out of character.

After soaking in the radiance, I scrounge up a bucket and find the well. Surely, while my back is turned and locked into rotating the crank that lowers the bucket, a monster will spawn behind me. I pull the water up and turn around. The moon hangs full and high in the sky. A few crows pass beneath it. I watch them fly away and then return to the warehouse. Night passes without incident.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Bored to breath

Anytime 35MM isn’t forcing me to listen to its stilted dialogue or endure its quicktime events, it’s very good at being quiet and pretty and sad. I like the combination of those things.

Moving the plot forward is only doable via awkward triggers—interactive objects just barely light up when the cursor passes over them—and it can be easy to lose your partner while running about an entire village. The ambient music is far too loud in the mix and washes out nearly everything else. And, technically, the 35MM super limited—no resolutions above 1920x1080 are supported. It’s got a lot of issues.

But lighting those candles in the church, watching the horizon take shape on the back of a makeshift rail car, or scanning the treetops for the source of a particularly pretty bird call–they’re all brief glimpses of energy and light in an otherwise cold and quiet world. As a window into the indifferent psyche of these characters and the bleak regularity of post-apocalypse rural Russia, it works. 35MM is best digested as a series of these interconnected vignettes rather than a cohesive, pristine whole—a reminder that pushing through a game’s imperfections is a healthy study of the many pieces required to pull off a grand illusion, and that at the heart of most games, messy or not, is the earnest intent of its creators. I can’t outright recommend 35MM, but its subdued vistas and long walks were enough to get me thinking about their counterparts in my life —foggy days, car horns, daily train rides, the light beneath a billboard—and what kind of comfort I can find in my own brand of mundanity.

James is stuck in an endless loop, playing the Dark Souls games on repeat until Elden Ring and Silksong set him free. He's a truffle pig for indie horror and weird FPS games too, seeking out games that actively hurt to play. Otherwise he's wandering Austin, identifying mushrooms and doodling grackles.