The gamification of gaming has reached new levels of meta weirdness

With Steam sales, Twitch, and Kickstarter, playing games is increasingly a game itself.

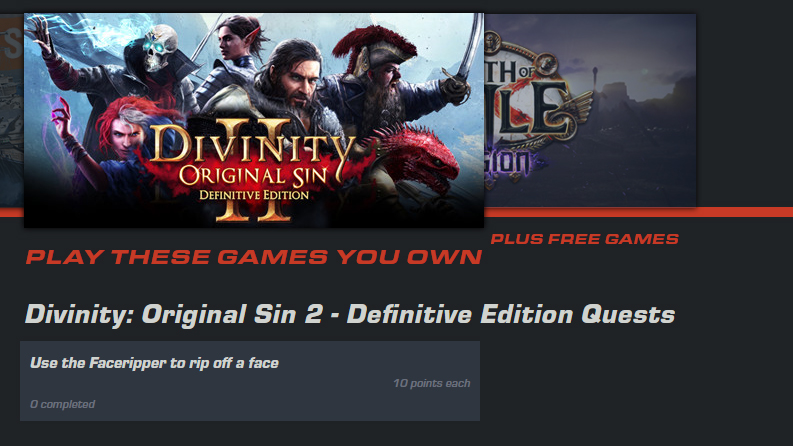

Steam has given me a quest: "Use the Faceripper to rip off a face" in Divinity: Original Sin 2. When I think about one of my all-time favorite RPGs in those terms, it seems like a very different game—a game in which I primarily rip off faces. But if I rip a face off it'll help Team Hare win the Steam Summer Sale Grand Prix, so maybe I should just get to face-stealing for my fellow Jackrabbits.

Side note: Everyone jumping on the Team Corgi bandwagon is a fool, because if you're on a smaller team you're more likely to win a game off your wishlist should that team place in the top three. Go Team Hare.

Back to my point: If I load up a save in Original Sin 2 and go around ripping faces off, am I playing Original Sin 2 or am I playing Steam? In my view, it's Steam more than Original Sin 2. I would have no reason to rip off any faces right now were Steam not telling me to.

I'm gesturing vaguely at a vague point here, but I think it's worth thinking about the gamification of gaming—the higher level games we play while we play games, and the disappearing lines between them—even if we don't come to any hard conclusions right now.

The game of gaming

The gamification of Steam largely began with its Team Fortress 2 marketplace, which was a sort of an economic game of hats, in one sense of the undefinable word. With the expanded marketplace, the addition of the profile rank and badges system, trading cards, and Steam Sales which include teams and quests and phrases like "Fill your Boost Meter with points & Nitro," the Steam metagame has grown into a much broader shape since then.

I'm surprised that other companies, namely those with their own launchers, haven't gone the same route. Microsoft basically started this with Xbox Achievements, which added a meta layer that superficially connected every game, but it hasn't gone nearly as far as Valve, and neither has Ubisoft, EA, Blizzard, or Epic. With the new adoption of subscription services, I suspect this may change.

(This also partly explains the negative reaction to the Epic Store. It's not just that having to use a new, underdeveloped launcher is a nuisance, but that Steam has incorporated its games into a total Steam experience—a metagame of discovery, social interaction and status, inventory management, deal hunting, achievement collecting, and so on. Right now, Epic's launcher isn't a very interesting game of games.)

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There's a sort of game to review bombing, in that people cooperate to lower a game's score.

Whether or not it's as explicit as Valve makes it, though, the gamification of buying and playing and even developing games is not limited to Steam's systems. There's a sort of game to review bombing, in that people cooperate to lower a game's score, achieving a quantifiable victory over an algorithm. And there's a game to monitoring Twitch and concurrent player statistics to determine which games are 'winning,' as if it's a race in which the finish line keeps moving further away.

Twitch itself added an achievement system to guide streamers toward affiliate and partner statuses, using progress bars that mimic quest progress in a videogame. And stream viewers participate in their own way, ritualistically dropping 'F's or other contextual phrases and emotes in the chat—like call-and-response chants in an arena. People aren't just 'watching others play games' on Twitch. They're participating in social play that sometimes seems more important than what's happening on the stream. (Or even playing the game themselves.)

On this trajectory, how much more will watching games, playing games, and buying games blur together? It already seems that today, PC games are viewed as aspects of their launchers rather than individual executables, and even as aspects of Twitch. There were cries that Apex Legends had 'died' due to a decline in Twitch streamers. (It is alive, at last check.)

The game of life

The development of games has also been subject to gamification, as common indie funding route Kickstarter presents a game-like veneer. There's a meter to fill, and there are 'stretch goals' which feel similar to optional quest objectives that the backers (by adding more money) and the developers (by building them) collaborate on. Developing a game is nothing like playing a game, but it can certainly be perceived that way.

Other jobs are. KFC made a VR employee training game, and some Amazon workers are literally 'playing' game representations of the labor they're doing.

"Developed by Amazon, the games are displayed on small screens at employees’ workstations," writes Washington Post reporter Greg Bensinger. "As robots wheel giant shelves up to each workstation, lights or screens indicate which item the worker needs to put into a bin. The games can register the completion of the task, which is tracked by scanning devices, and can pit individuals, teams or entire floors in a race to pick or stow Lego sets, cellphone cases or dish soap, for instance."

Talking to each other has become a game, too, as social media sites use game design principles to keep people hooked, and Youtubers 'game' the algorithm to increase their audience. When working is a game, and buying things is a game, and socializing is a game, and even playing games is somehow a game, Marshall McLuhan's concept of the "global village" may need to be replaced with the "global videogame."

To return to my much smaller original point, though, please step it up if you're on Team Hare. Go rip some faces off for the team.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.