The anatomy of hype: how No Man’s Sky became the best and worst game ever

No Man's Sky is a perfect example of unrestricted expectations crashing into reality. So who's responsible?

We thought maybe we could meet other players in No Man’s Sky. We were told as much in vague terms, over the course of a couple years, but so far that expectation has gone unmet. It’s also been heavily qualified, to the point of Hello Games founder Sean Murray reminding everyone just before launch that No Man’s Sky is a single-player game, while still remaining somewhat cryptic about what might happen if two players meet. So far, nothing has happened.

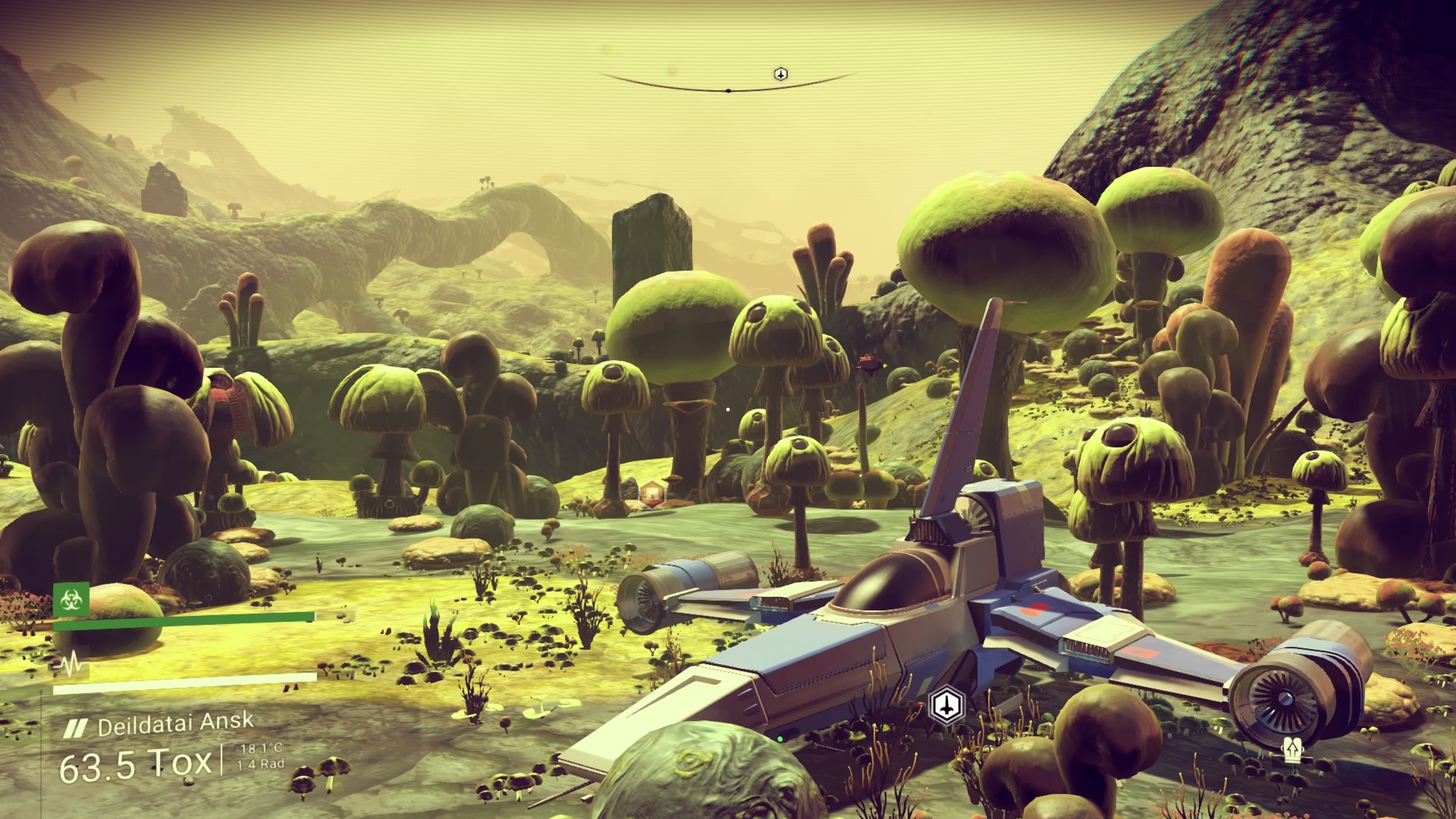

The confusion over this point has made more than a few people upset, as has the pièce de résistance of No Man’s Sky: procedurally-generated planets, which of course can only have so much meaningful variance. It’s technically infinite but not really: the rocks and life you’ll see out in space look a bit like the rocks and life other people see. It’s not everything everyone imagined or entirely in line with the well-produced trailers, which only showed snippets of impressive procedural capability. And now some fans are defending No Man’s Sky like it’s their baby, others are disappointed and angry at Hello Games, others are gloating because they were more skeptical. The discussion has turned to hype and its inevitable fallout, an ocean of anger and blame.

Blame games

We at PC Gamer are to blame for the hype, according to some, and that’s always at least a little bit true, because we have a large platform—as do other websites and magazines and YouTubers and popular subreddit moderators. But I don’t think we were wrong to be excited about No Man’s Sky. A couple of us like it so far, and even those in the office who don’t like it recognize that it’s an exciting and unique game—a huge procedurally-generated universe full of planets no one has ever seen before. We allow ourselves to look forward to things, to be excited, to be disappointed or gratified and to report on that experience. So while the rest of the world was getting excited about a cool trailer out of the 2014 Spike VGAs, we were too.

We were so uncertain about the true nature of No Man’s Sky that, a month ago, we realized we all had competing ideas about what it was.

We also have a responsibility to approach claims critically, though, and in this case we were so uncertain about the true nature of No Man’s Sky that, a month ago, we realized we all had competing ideas about what it was. So we picked through all the trailers and interviews to try to put together a single vision—but we couldn’t, and so we qualified a few bits with question marks. It’s our job to share information, but in an age where playing a game for two years before it’s complete isn’t abnormal, a lot of us got caught up in the idea of No Man’s Sky offering the surprises and mystery that seem so rare in modern games.

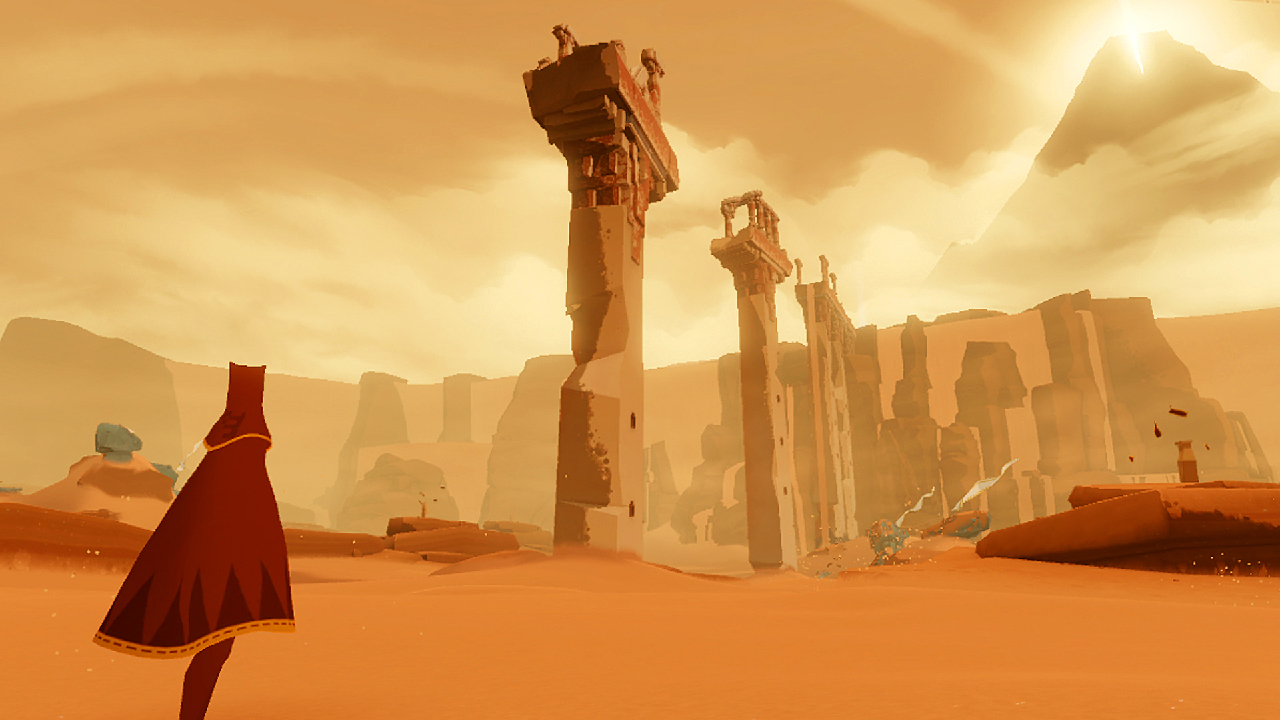

To Murray’s credit, he’s been consistent in saying that No Man’s Sky isn’t an MMO, and that it isn’t focused on multiplayer. But No Man’s Sky’s pitch isn’t a single feature, or a story, or an action—it’s the romantic notion of infinity, the idea of algorithms that create life, science fiction here and now. It’s a container that can hold anything at all, so when Murray compared No Man’s Sky to Journey and Dark Souls—two games with well-defined multiplayer—and said we’d have a personal ‘lobby’ around us and could see other players, the idea fit into the box with ease. Multiplayer, however qualified, became part of the infinity.

Until I went back and studied the trailers and interviews, I had a totally made-up version of the game in my head.

In a 2014 interview with Game Informer, Murray said he was worried about disappointing people, and that they might imagine things in the game that aren’t there, or that are impossible. It was already too late. When asked if No Man’s Sky included multiplayer, Murray didn’t say “no.” He seemed to want us to discover it on our own, to let little surprises be surprises—but that created holes in our understanding, which we filled with speculation.

Even as Murray said again and again that it would be nearly impossible for players to meet, I'm not sure everyone believed him. Why build it into the game, then? Why talk about it in interviews?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It’s natural to do this: we interpret things through our own logic and experiences, and when we don’t have all the information, we use our imaginations. Sometimes we confabulate (though not in a medically serious way), fill in gaps of information with false information, or seek out information that confirms our assumptions. There was a brief period early after its announcement when I thought No Man’s Sky could be described as a multiplayer space trading game. I’d seen snippets of interviews, heard second-hand sources talk about it, and that’s the conclusion I arrived at—probably influenced by the existence of EVE Online, Elite: Dangerous, and Star Citizen. Until I went back and studied the trailers and interviews, I had a totally made-up version of the game in my head. But even after I righted my perception, I still didn’t really know what it was all about. I still thought that other players just might fly around in my systems, and I could follow them around—like Journey.

And as we’re seeing in the battle over the Steam user reviews, over 36,000 of which add up to a ‘mixed’ rating, when imagined experiences don’t live up to the real thing, the disappointment can be monstrous.

Great expectations

When I was nine, my grandfather promised that I could go ice fishing, but not until I was 11. At that age, two years felt like the distant future. Every couple months I’d remember and repeat it like a mantra: ‘When I’m 11 I can go ice fishing.’ I imagined a big hole in the ice I could stick my hand into—whatever image I’d seen on cartoons—and how cold the water would feel, and how big the fish would be, and how we wouldn’t even need a cooler because we could just pack them in snow. The adults around me, meanwhile, were doing other things: getting sick, getting better, getting divorced, losing their jobs, forgetting about ice fishing. I turned 11 and we didn’t go ice fishing.

Losing an experience—or perceiving that loss—is a big blow.

Not long after the idea of that trip dissipated, my grandmother died, and my grandfather died a year after that. I was a teenager then, and I didn’t care about going ice fishing anymore. But even though I moved on—because of course I did, it was just a damn ice fishing trip, an offhand comment that only I remembered—I can still feel the disappointment of 11-year-old me. Losing an experience—or perceiving that loss—is a big blow. It’s far a greater loss, I think, than a movie I was looking forward to being crappy. The experience of going to see a movie with friends is still there even if the movie sucks, but with games like No Man’s Sky the experiences we expect are virtual, embedded within the code and design.

In retrospect, I probably would’ve hated ice fishing. It’s cold and boring. In all likelihood, it was just a quiet shed where my grandfather could drink and smoke cigars. But I built it into something mythic, some vital bonding experience that would’ve sealed my perspective on the world, a profound communion with nature and family. It speaks to how powerful my anticipation of experiences is, and what my imagination does to them over time.

Take Star Citizen, for example: it’s a travel agency. Well before there was any game, backers were buying ships and reading every scrap of promise and planning their trips. There’s a bit more of a game now, but they’re still deciding if they’ll be fighters or traders, how they’ll bring their friends along with them, where they’ll go and what they’ll see—still looking forward to and planning experiences they can’t have yet. There’s even a whole forum section dedicated to roleplaying, with one thread asking, “How do you plan to ‘handle’ non role-players in an RP live stream?” In a way, Star Citizen has been selling the actual experience as much as the permission to fantasize about that experience for years before it’s implemented. Pre-orders operate on the same premise.

The idea that every other person who makes a game is an unrepentant liar is inordinately cynical.

The planning is the hype, and it takes very little to spark it. It can start with just the word ‘multiplayer,’ uttered in a cloud of qualifying words, and then grow in imaginations, become amazing things we’re going to do when the game is out, and oh, why can’t it be out sooner? And that’s good for developers in that it drives sales, but I’m not calling conspiracy on Hello Games or anyone else. The idea that every other person who makes a game is an unrepentant liar is inordinately cynical. Much more often, I think unfulfilled promises are miscommunicated promises, or abandoned because of sloppy management, or abandoned because they were too optimistic to begin with, or because they just didn’t work, or because they grew in unanticipated ways.

Some of the scenes in BioShock Infinite’s trailers weren’t in the game at all, for instance, and there was also a time when it was going to have multiplayer. “So much of it is experimental that you really have no idea,” Ken Levine told IGN in 2012. “When you’re making a game about Marines fighting the Taliban, you sort of a clear path to go with. In a game like this, where we start this thing and we’re like ‘OK, it’s in a flying city in 1912 and you’re this guy and there’s this girl who can change the nature of reality,’ you don’t quite have a lot of guidelines to go with.” No Man’s Sky, a game about exploring infinite worlds, has even fewer guidelines.

So I don’t think that Sean Murray and Hello Games wanted to release a game that purported to be something it’s not—Murray’s letter last Monday is evidence of that. But the hype was too strong to be defeated at the 11th hour, and while I’m enjoying No Man’s Sky, something I was skeptical about but wanted to find value in, for some it’s becoming an ice fishing trip that never happened.

Its promise of infinity left it open to infinite imaginary versions of what it could be.

I also don’t think hype can fully be stopped. Some hype is uncontrollable, and because what No Man’s Sky offers is so unusual and open-ended, the only way it could have avoided unrealistic expectations would’ve been for it to go entirely unmarketed, a surprise release on Early Access. Its promise of infinity left it open to infinite imaginary versions of what it could be. A multiplayer space trading game, for instance. In reality, it's a more standard survival game.

But developers and marketers (the same thing, often) still have a responsibility to be explicit in describing the heart of their work. They can’t control what our imaginations generate with the seeds of ideas they put out, but they can at least decide which seeds they’re putting in the ground. I don’t doubt that it’s a challenge. Through trailers and interviews they have to maintain a consistent and realistic description of something they’re close to, excited about, thinking about in terms they’ve invented that we might not understand. Games are complex and development is a winding road and things change. Dealing with that road is what PR departments are for, something Hello Games lacks internally—Murray himself once told Game Informer he doesn’t read the press, or have much of a publicity plan. I think it might have helped. While we love unrestrained developers who are willing to talk about anything—as opposed to carefully coached spokespeople—there were avoidable errors here. The comparisons to Journey especially set false expectations.

Fuel for the fire

Then again, Hello Games is a small developer, and PR costs money, and what the hell, people like mysterious and exciting trailers, right? No Man’s Sky has done extraordinarily well off the back of them, even despite the controversy, tepid reviews, and widespread technical issues. Curiosity made it the biggest launch of the year, and there’s no doubt we at PC Gamer have been curious for the past few years. We’ve been anticipating No Man’s Sky and speculating about its mysteries. We like talking about the things we’re interested in and we know people want to read about them. What will Mass Effect: Andromeda be like? What can we glean from the E3 2016 trailer? It’s fun to talk about.

But are we contributing to the hype? Of course we are.

Last week we published over 20 stories about No Man’s Sky. We wrote impressions of our first couple days playing it on PS4, published a guide to getting started, collected some of the interesting things players have found so far, and published an op-ed on what it can learn from Kerbal Space Program. We reported on Murray’s letter, on two players meeting and nothing happening, on the launch issues, and on what happens at the end. Our readers are interested in reading about No Man’s Sky, and we can measure that easily. But are we contributing to the hype?

Of course we are. If we wanted to, we could refuse to cover No Man’s Sky at all—perhaps slightly diminishing the buzz, but probably not. Except that would be like a sports publication refusing to cover the Olympics because people are too interested in reading about the Olympics.

Our responsibility (as we’ve defined it) is not to ignore highly-anticipated games so that expectations aren’t raised too high, but to learn what we can from their creators, inform, advise, criticize, and sometimes just invite readers to have fun with us, like when we asked you to design a good Priest card for Hearthstone. And by covering highly-anticipated games a lot, we give ourselves the chance to investigate specious claims and produce criticism and make sure these games aren’t released to the sound of marketing alone. There should be opinions and discussions and reporting outside of advertising, and we fail if we stop asking questions.

There's a difference between putting out coy, ‘spoiler free’ trailers and seeding misconceptions.

Meanwhile, it’s a developer or publisher’s responsibility to answer those questions truthfully, or avoid marketing that’s so cryptic it can be easily perceived wrongly. There's a difference between putting out coy, ‘spoiler free’ trailers and seeding misconceptions. Mysterious Mass Effect: Andromeda teasers and fan speculation about the story is a bit of low stakes fun. The marketing of Aliens: Colonial Marines, however, which promoted something very different than what was released, was a mess that drew justifiable public anger.

No Man's Sky certainly isn't a Colonial Marines-grade situation, but it's a perfect encapsulation of the hype process: mysterious claims followed by wonder and anticipation followed by a furious choruses of disappointment and defense. While the developers may have been thinking 'single-player crafting game' this whole time, many others clearly were not, and Murray's statements played a part in that.

And even the smallest bits of communication are immensely important, because when I hear offhand remarks about some potential multiplayer thing that kind of maybe lets me meet up with friends, I start making plans. I imagine a certain kind of trip, and if you give me two years to look forward to that trip, it’ll start to feel like something real and you may end up having to tell me, and everyone, a day before your game releases, that we might have been imagining the wrong thing. We’re not going ice fishing after all. Whatever the merits of the alternative, no one is going to be happy about that.

Unless, of course, two players do meet up again in No Man’s Sky and it does work—whatever ‘it’ is—and it’s the most amazing thing ever, a brilliant trick that validates every optimistic opinion about the game, and solves all my emotional problems, too—something really transcendent, you know? In that case, nevermind.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.