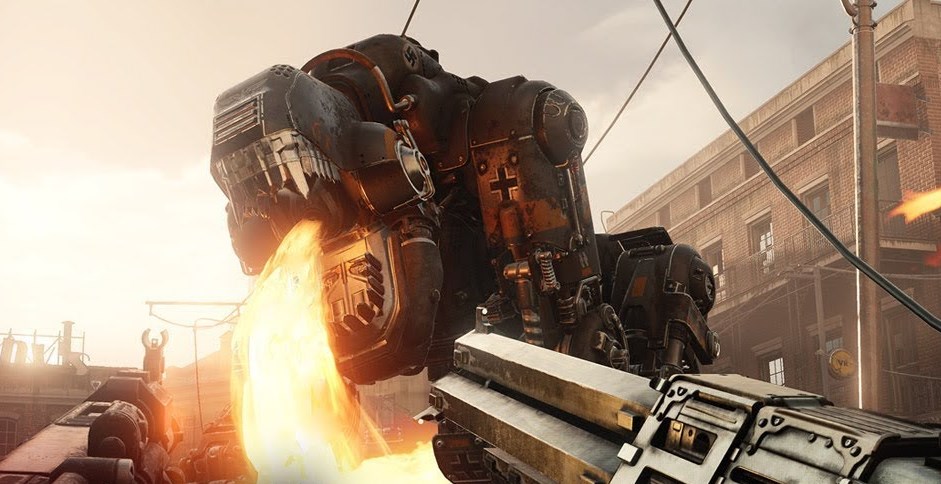

More than 3,000 Nazis die in Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus

A chat with creative director Jens Matthies about influences, gunplay and sudden topicality.

When Wolfenstein: The New Order released in 2014, it was just another shooting game. A bloody excellent shooting game, yes, but in terms of its reception in the greater, non-gaming world: a non-event.

Fast forward to 2017, and Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus is attracting a fair bit more attention than its predecessor did pre-release—especially off the back of last week's "Make America Nazi-Free Again" trailer. It's doing so because, at a time when racist intolerance and bigotry is alarmingly foregrounded in American life, "embracing an anti-Nazi stance" can, in some quarters—unaccountably, scarily—appear quite brave.

Bethesda's Pete Hines made his company's vehemently anti-Nazi stance explicit last week, while also adding that Wolfenstein 2's depiction of a United States ruled by a fascist regime is a "pure coincidence". But it's still a timely game, disturbingly enough, and I sat down with its creative director Jens Matthies to talk about this stuff, as well as a bunch more.

Jens is the creative director of Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus, as well as its predecessor The New Order. He's also a co-founder of Machine Games.

PC Gamer: You might not have the figures on hand, but a lot of Nazis die in this game. How many roughly? Can you give us a figure?

Jens Matthies: I can probably give you a figure but I have to think about that.

[Jens picks up his phone and, after a minute of complete silence, continues.]

I would say, close to a thousand. That’s what I think. That’s a little bit speculative, but in the neighbourhood of one thousand. Let me revise that: I mean about a thousand personal kills, but then there are a few thousand impersonal kills as well.

I’m happy with that figure. When The New Order came out it wasn’t such a big deal that you were mowing down Nazis in a video game en masse. But in 2017 it is. Pete Hines even addressed it directly last week. What’s your personal response to Wolfenstein suddenly being a cathartic and timely game, given the current political environment?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

JM: Well, it is quite a coincidence because that’s actually the theme of the game: catharsis, in terms of the narrative. While I don’t think it’s ever a good thing to have Nazis marching anywhere in the real world, if a feeling of catharsis is what you’re after, then this game is for you.

Nazis have come to be a kind of generic comic evil in games, in the same vein as zombies. Until recently we’ve felt so remote from that history that we can just mindlessly kill them. But I was wondering, speculatively, if you were to make a third instalment, would you address the depiction of Nazis or go about the narrative any differently?

JM: No. We feel very strongly about the stories that we’re telling. This game is painted on a very grand canvas: it’s over the top and it’s bombastic and it’s pulpy. But it’s also... we never wanted to undermine or make light of what Nazi ideology is actually about. So even though we’re sort of representing it in this larger-than-life canvas, it’s not a cartoon in that sense.

We feel like that’s something we established with the first game and continue in this game. If we get the privilege of making the third entry in the trilogy, that’s what we’d continue to do. If you’re all the time worrying about the world and what other people are thinking and saying, then you stop being a good creative.

The tone is pulpy, but one of the things that elevated The New Order, and made it easier to engage with, is the fact that the characters had humanity about them—particularly, surprisingly, BJ. Are there any film makers that inspire MachineGames?

JM: Oh yeah. That’s always what we’re going for, that juxtaposition of things that are very over the top with things that are incredibly intimate and domestic and normal. And we love those authentic feeling relationships—that’s what we want the game to be about. Examples of that are the original RoboCop, which has that vibe. More than anything else, I think that’s an inspiration to me personally because seeing that as a kid was a formative experience. There are other examples: District 9 straddles that line as well, maybe Guardians of the Galaxy, though that’s extremely humorous in a way that we’re not really. Our humor is a lot darker, but it’s still on that spectrum. And of course some Tarantino movies are like that too.

One of the interesting things about Wolfenstein is that it’s marketed as this heavy duty cathartic shooting game, but it’s actually quite tough. It’s a really challenging game.

JM: Of course it is, depending on your difficulty settings. I mean, if you just want to experience the story you can just dial down the difficulty and more or less walk through it. But it’s always more fun, we feel, especially in a game with real old school merits, if it’s a real challenge. It also leads to players needing to think creatively, in ways that many games don’t allow you to do nowadays. If you run into a challenge that’s tricky to overcome, that means you need to re-examine the situation. Maybe if I try it in this order, and use these weapons, and maybe even sneak for a bit and then do this… this is the kind of game where you have a lot of those tools and options, and the combat areas are open to a lot of exploration and approaches. You can observe and figure them out, and most have a certain logic to them. So in order to encourage that kind of gameplay it has to be a little hard, and you have to die a few times just to probe the problem and figure it out.

I’m put in mind of Hotline Miami—you have to figure out a wise sequence, it has a puzzle dynamic.

JM: Yeah, and if that’s not for you you can turn down the difficulty and be more straightforward in your approach. But for the standard experience, you want that cerebral dimension of it, where it’s not just about going through the paces but actually figuring the problem out.

You’re using a new engine, and it seems to me it’d take a lot of effort to basically create the game afresh.

JM: Oh yeah. Oooh yeah.

But you’ve still retained the feel of the weaponry. There’s a certain quality that has carried over.

JM: We were extremely happy with what we accomplished in The New Order. We felt that was a good, really strong feeling of Wolfenstein. So for sure we wanted to preserve that, but also kick it up to the next level. We really wanted to get back to having a full body model, because in New Order you were basically a disembodied arm / gun / first-person model. So if you look down you have no legs. But in this game it’s a full body model, which in itself is incredibly much more work, but we have a dedicated team who is super passionate about the first-person experience.

Were there any overarching philosophies regarding the shooting approach? Obviously it feels different to anything else, but in subtle ways. What were the guiding values?

JM: It’s interesting because I don’t think I’ve ever put words to it before, but we always wanted to be just, I guess, meatier, and just fucking… more heavy metal than anything else. So our stated goal was that we wanted to reach the level where this was the best first-person experience you can have in terms of combat and movement. I’m very happy with how it came out because it’s very noticeable that if you play The New Colossus for a few hours and then you start playing something else, everything feels a lot different. So yeah, I think we’re evolving with what we did with The New Order to a new level.

Do you think it helps your gunplay that multiplayer isn’t a factor? Could it work in multiplayer?

JM: I’m sure it could, but I’m sure there would be problems as well. But for sure, having everyone focused on the same problem is what historically has always resulted in our best work. So that’s always what we’ve tried to do and that’s why we don’t do multiplayer. But I think if we did do multiplayer, I’m sure we could get to something of that same level.

I like that The New Colossus feels like a filmic sequel—it’s not about just adding stuff, like so many game sequels are, it’s a new story. Has there been any desire to do stuff like that, add an open world, add more stuff?

JM: I don’t know, we constantly think about stuff that we want to do and I wouldn’t at all be opposed to doing different formats. But of course, we have this… I wouldn’t say that we have this story that we want to tell—we do of course—but it’s more than that. We have an experience that we want to create. We always envisioned it as a trilogy, and so if we get to do one more, if the game does well enough to motivate that, then I can guarantee that it will be a worthy sequel. How that shapes out and what its form is, we’d have to see.

What’s your relationship with the first Wolfenstein 3D? Do you resort to it as a primary, kind of bibilcal text? Or have things moved on so much that it barely factors in?

JM: No way, to us that’s the foundation with our approach to Wolfenstein. It’s not biblical in the sense that we’re being literalist about it, but the ethos that propelled and created Wolfenstein 3D is what we’re literal about. Analysing what went on there, this was id Software coming into their own, having broken away from wherever they were before and barely in their teens, sitting in some apartment somewhere making these things that no one else is making. That people don’t even think is possible. That’s what they’re doing and they’re just forcing their totally unrestricted creativity into that project, and that’s what we wanted to go for: if we think it’s a cool idea and it belongs in the game, it goes into the game. We don’t try to censor ourselves and say “would that really fit with blah blah”. That doesn’t mean we don’t want to make it credible in the game world, we care about that stuff, but we don’t put any boundaries on ourselves. So that’s what we’re trying to carry on.

Shaun Prescott is the Australian editor of PC Gamer. With over ten years experience covering the games industry, his work has appeared on GamesRadar+, TechRadar, The Guardian, PLAY Magazine, the Sydney Morning Herald, and more. Specific interests include indie games, obscure Metroidvanias, speedrunning, experimental games and FPSs. He thinks Lulu by Metallica and Lou Reed is an all-time classic that will receive its due critical reappraisal one day.