The history of Championship Manager and Football Manager

How football management games stole all of our spare time.

Retro Gamer is an award-winning monthly magazine dedicated to classic games, with in-depth features from across gaming history. You can subscribe in print or digital no matter where you are by clicking this link. This month's cover feature is Street Fighter—check out the amazing cover here.

Every couple of weeks we feature a new guest article from our friends at Retro Gamer magazine, with their permission. This week, it's the history of Championship Manager and Football Manager, originally published in issue 178 in February 2018.

The series once known as Championship Manager, now Football Manager, turned 25 years old in 2017—but its story begins further back than that, in 1985. Two brothers, Paul and Oliver ‘Ov’ Collyer, decided to try and make their own game of soccer management from their Shropshire home. “We were playing the other games—League Division One, Mexico ‘86, the sort of international version of it, and Football Manager,” Ov explains. “[We were] checking out all the other games of the time, and deciding we didn’t like them very much so, in our arrogance, deciding that we might be able to do it better.”

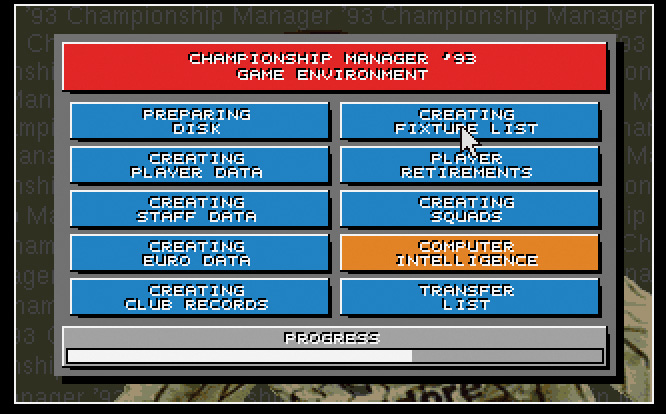

This ambition took time to bloom, however, with the original Championship Manager being worked on here and there for six years before it was finished in 1991, and released in 1992 for Amiga, Atari ST and, shortly afterwards, PC. A big reason why it took so long was that… well, Paul and Ov were in school and college, literally bedroom-coding the game. “There were times when maybe six months would go by when we didn’t do anything on it,” Ov explains. “The other side of it was when we’d spend our holidays locked in the attic just trying to make it better.”

And better things got—as the project took shape, the brothers starting hawking their wares to publishers around Britain, trying to get their new take on an established genre noticed. There were knockbacks, of course, with Electronic Arts turning Championship Manager down for not featuring enough ‘live action’. “The ‘no graphics’ thing was a big thing,” Ov says of another publisher’s feedback. “I remember ‘bolt some graphics on there’ was the exact phrase used.” But one company expressed an interest, and Paul and Ov put their game in front of publishing house Domark. The rest, as they say, is a funny old game—and a slow, drawn out slide into professionalism.

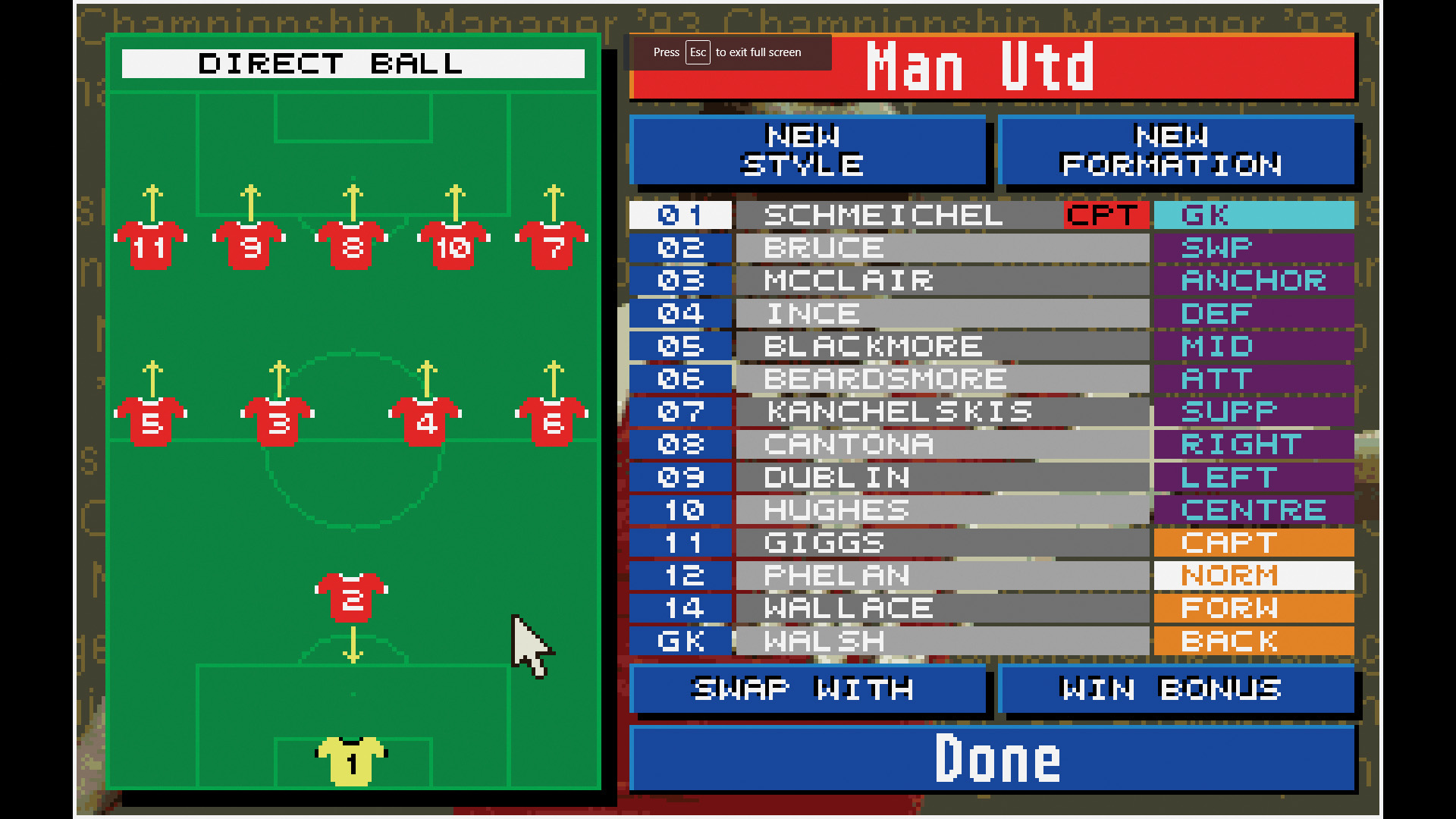

The original Championship Manager might have been the beginning of a series with seemingly eternal appeal, but as a game it’s all but forgotten—immediately trumped by CM ’93 bringing with it real player names, and that’s where the hardcore football fans started to take notice. While, at the same time, critics started to miss the point.

“The good reviews made us happy—the shit reviews made us miserable,” Ov laughs. “It was kind of depressing to read something really bad—you’d feel angry because we knew people were enjoying the game. But I guess we did have some really good supporters in the computer press. PC Zone got on board with it, I remember. We had our supporters, and we had others who just didn’t get it at all.” Even without the unanimous backing of the early Nineties gaming media, though, Championship Manager sold well enough that a sequel was on the cards—at least after a detour to the continent.

“Italian football was the main league people were watching, I think because of Channel 4’s coverage started around then,” Paul Collyer explains of the brothers’ decision to make Championship Manager Italia—a continental-themed update to the CM ’93 formula. “I guess we just thought people wanted to play an Italian version, with the leagues in it and so forth,” Ov adds.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

But it wasn’t as straightforward as it might seem, with Domark not actually on board with the decision to make the Italian league version of Championship Manager: “We took it to Domark and they didn’t want to do it,” Ov says. “So we ended up sort of half-publishing it ourselves, in the end they got on board and carried it on.” A move no established dev team would make with its publisher these days, of course, but back then it was two brothers who didn’t even have an office.

Italia performed well enough, but work on a sequel proper was commencing—and ambitions had grown off the back of a few years’ success in the lower leagues. And so, late in 1995 the ambitious, processor-and-RAM-hungry Championship Manager 2 hit and took the world by storm. The original might have opened some eyes, but Championship Manager 2 was a revelation with its incredible depth, realistic portrayal of the trials and tribulations of management and—for the first time—players with abilities ‘scouted’ by the Collyers’ studio, Sports Interactive, without just using a book of stats (we’ll get back to that).

An early casualty of the improvements in Championship Manager 2 was the Atari ST and—surprisingly, for the time—Amiga. “The Amiga and ST were the machines at the time,” Ov admits. “For us to turn around and say, ‘We’ve just written a sequel and it doesn’t work on the same platforms as the first one,’ it’s a little bit controversial. We had tried to do it on the Amiga and realised we couldn’t, the spec wasn’t sufficient to handle the game. So we said, ‘We can’t do this and we don’t think it’s a good idea.’” Two years later a truly terrible port of CM2 for the Amiga 1200 did release, but that was nothing to do with Sports Interactive or the Collyers. The brothers agree it should never have been released, but we won't dwell on that particular heartbreak.

CM2 (and its two expansions, for the 96/97 and 97/98 seasons) more than raised the bar. The confidence of the young, growing SI team was bolstered by the fact those making it were having fun and—in a slightly surprising revelation—because Doom was on tap in the single room of the house share in which the game was being made. “Doom was trying to put paid to our work on CM2,” Ov laughs. “That was exactly the time of Doom—it was a brilliant release. When you were working on the game and you needed a break, you’d just get Doom loaded up and it was completely the opposite… almost.”

That help was needed thanks to the newfound pressure on the team. This was no longer a new product—it was an established series with numerous releases under its belt. “It wasn’t like when we first wrote it in Shropshire when it was just a bit of fun for us,” Ov says. “This was something we knew people liked, so we had the situation where we had a little bit of pressure and a little bit of expectation.” This pressure and expectation merely spurred SI on.

Football Manager is part of the modern lexicon now, cited in as many sporting articles as it is academic papers

By this point the complexity of the real-world game had increased, so it wasn’t just a case of fitting in more real players and formations—CM2 had to include rule changes. One big change in the mid-'90s was the Bosman ruling, so named after Jean-Marc Bosman and his successful legal case allowing him to move clubs for no fee when his contract had expired. Including a complex ruling like this, even with the relatively amateur setup the Collyers still had, was never in doubt: Championship Manager was always about accuracy. And it’s always been about building a world around this realism.

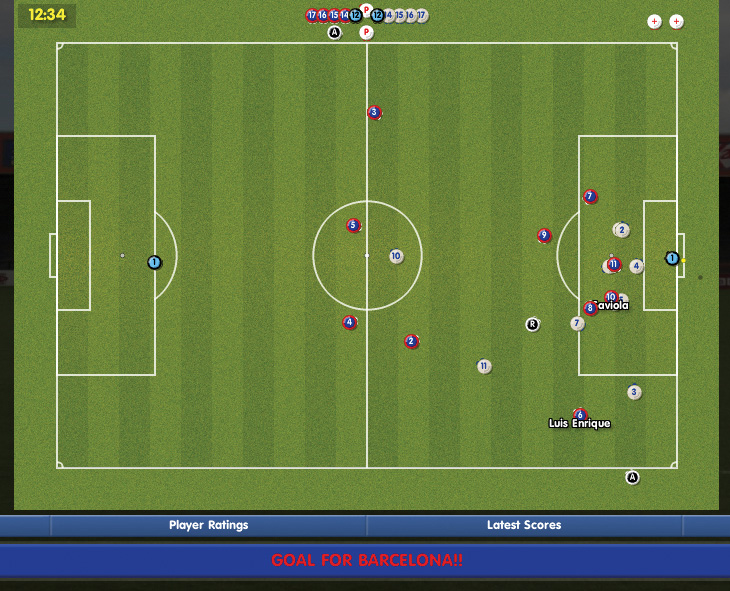

“The thing that Ov said, and it’s always stuck with me,” Miles Jacobson, studio director at Sports Interactive, interjects, “was that they were trying to create a football universe. Everyone else was creating a football game, and it might reset at the end of every year so it didn’t matter, it didn’t really interact with other teams, they didn’t really have players apart from [a basic] transfer market which would come through once a week when you’d be offered one player. But he said they didn’t care whether a human was playing or a computer manager was playing—the game would carry on because it would be a living, breathing world. That’s what we’ve always tried to do ever since then.”

Something very few would have predicted over the lifetime of Championship (and Football) Manager was just how influential the game series would become in the real world, thanks in no small part to the breathing world Sports Interactive created. We’ve all heard stories from other sports games where an athlete commented on their in-game stats, or seen a game take the bold step of having accurate kits, stadia and player faces in it—but the balance swiftly changed the other way when it came to Championship Manager, thanks to one key element: data.

Thanks to the power of crowdsourced information, Championship Manager was able to establish a footing in the realm of real-world player scouting early on, after having relied on information in the Rothmans Yearbook for the first couple of releases. Around CM2 the team began contacting fanzine writers for specific clubs and getting information from them on their teams, the players and who to watch out for in the future. It wasn’t always reliable, but it offered a much more genuine representation of teams and their players—especially in the lower leagues. Asking for direction from a local is always the way to go with specialised knowledge, and Sports Ineractive built on this with each iteration.

These days you’re looking at a scouting network comprising of thousands of individuals looking at around 2,200 clubs in 51 countries, along with an additional 2,000 or so lower league clubs covered in less detail. It is, without a shadow of a doubt, the largest single player scouting network in any sport in the entire world, and it’s all to make sure the data in a computer game is as accurate as it can be. So is it any surprise teams started knocking on SI’s doors, with Premier League club Everton officially licensing Football Manager’s database back in 2008?

There’d been a build towards this embracing of the series by the footballing establishment, with anecdotal tales popping up all around of players offering their coaches advice on little-known opposition players by showing them said players in-game, lower league managers using Championship Manager as a £30 worldwide scouting tool to discover potential new playing talent—or even former Tottenham Hotspur manager Andre Villas-Boas, whose self-confessed love for Championship and Football Manager contributed directly to his role as chief scout at Chelsea. By no means were these people using the game as a stand-in for reality, but its accuracy and utility hasn’t been in doubt for the last decade-and-a-half. Football Manager is a game, but it's also a tool for the professionals.

At the same time, Championship Manager was becoming more of a game made by professionals—increasing sales and exposure meant more revenue, while changes at Domark (now Eidos following a merger) were pushing everything towards a more traditional publisher-developer relationship for CM3. “We were more of a serious operation,” Paul explains. “I remember people staying up for three days because we were about to submit the finished version of CM3.”

So maybe not that serious yet, then. “We had a competition to see who could stay up the longest,” Miles laughs. “Thankfully, I wasn’t programming at the time, because I was hallucinating dinosaurs.” One thing that certainly stayed the same was the team’s love of the first-person shooters of the day—and for CM3 it was Duke Nukem 3D taking up more time than it maybe should have. “When you talk about CM3, I think of Duke Nukem,” Ov says. “I visualise a darkened office with everybody peering into their screens, sound coming out of their little speakers and explosions ringing out of the whole office. It was the perfect way to relax after half an hour of coding. Then six hours of Duke Nukem, followed by a phonecall to explain why the game’s late.”

But the hard work was present for all to see with CM3. It was refined for the 00/01 update, but when Championship Manager 01/02 hit, something larger happened. The game has gone down in legend and is still played to this day (“By a lot less people than you imagine,” according to Miles), with players still sharing their stories online and reliving the tale of bagging Tonton Zola Moukoko for a hundred grand.

“It’s a great game, something we’re all very proud of,” Miles says. “It’s probably what CM3 should have been in the first place—I think less Duke Nukem was played that year.” A big reason why there was more polish was down to Miles’ move from general helper and friend of the Collyers to being asked to run the business side of the operation, with neither of the brothers wanting to get involved with that side of things.

Miles’ impact was immediate. “Rather than letting money just sit there in a bank account I was suggesting weird things like, ‘Why don’t we hire more programmers?’” he explains. “So there was a bit of a hiring push at that point—a lot of those people are still with the studio now—we also added a QA team for 01/02—all the QA had been done before [externally]. It was still a lot of fun, but there was more work getting done.”

“CM2 was still based on bedroom code,” Paul adds. “So it was CM3 [and the updates] that were literally done in the studio, writing code, in a more professional manner. It really mattered if things were late or not—it always mattered—but it mattered more. CM3 definitely was a sea change in terms of the studio’s approach, absolutely.”

That change didn’t mean everything would remain rosy, however, as an increasingly tense relationship with Eidos and the stresses of having worked on a single series for over a decade began to take their toll. “We totally overreached ourselves,” Paul admits of the fiasco that was Championship Manager 4. Released in 2003 it promised a huge overhaul of the CM formula, introducing a 2D match engine for the first time and met with a fevered response from the buying public on its release. That fervour soon turned to anger as players realised how buggy and clearly unfinished the game was.

We learned a lot from Championship Manager 4,” Miles explains. “We learned that if we’re going to be really ambitious with our games and hire loads of people, we actually had to have a structure as a business.” With Miles notionally working as a producer “not having a clue what I was doing”, the team was too close—blinded to the fact that CM4 was not a good game at launch. “We were also blinded by the fact that at that point journalism wasn’t as honest as it is now,” Miles adds. “There were some reviews that came in for CM4, we’d had 10/10 reviews because people had been told that all the bugs they were finding three days before release were all going to be fixed in the final version of the game.”

Paul remembers the slip-up with optimism, though. “Despite the fact it was a shit game and people bought it thinking it wasn’t going to be, it did benefit the studio and the future games,” he explains. “Sometimes you have to go through something difficult to be able to do something better in the future. I think we’ve grown in a more sustainable way. And we have structure.”

By the time CM4 hit the shelves, it had already been announced it would be the studio’s last game with the publisher. “It’s pretty difficult when you’re making the most in-depth, complicated football management simulation that has ever been attempted with Championship Manager 4,” Miles remembers. “And there are issues with your publisher as well. It made it a very difficult period. I tried to protect everyone from the issues, but it was clear that there were problems there.

“Mainly because they’d set up a studio called Beautiful Game Studios that they were claimed were doing a platform game.”

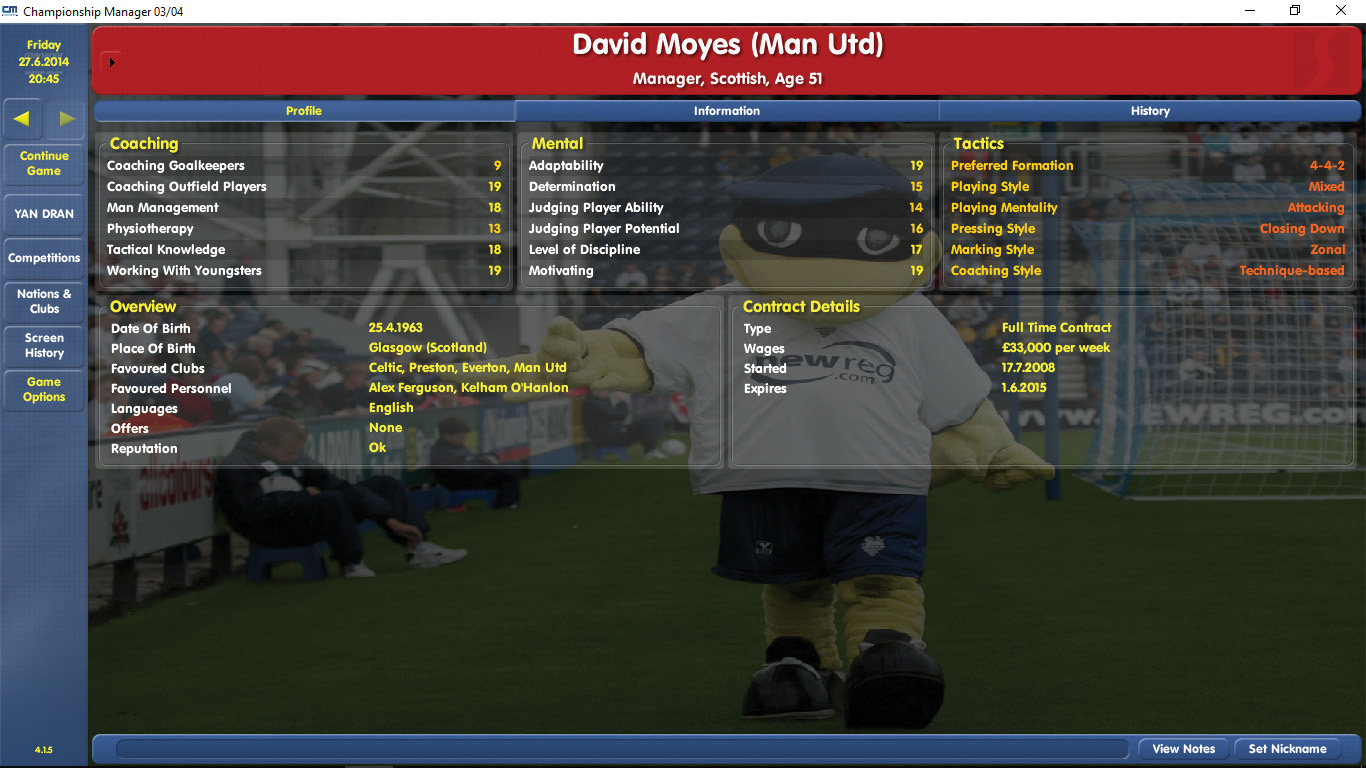

But it wasn’t quite the end of the working relationship, with redemption in the form of CM 03/04 coming as a result of Eidos needing to fill a gap opened in its release schedule. “We got rid of a bunch of issues by doing CM 03/04,” Miles says. “That was the game CM4 should have been.” But even with redemption for the team and its series, there was no going back on the move from under Eidos—and with the move came one of gaming’s most notorious splits.

“We were really excited about it,” Paul laughs, as Miles points out it was a mutual decision.

“But a bit nervous,” Ov interjects. “It was a contest to show which was important: was it the content of the game, or is it the name of the game? There was a worry that they would produce some kind of average game and it would be called Championship Manager, and everyone would buy that, whereas we might produce something we think is a really good game, but it would be called something else and nobody would buy it because nobody would have heard of it.”

It wasn’t hasty, though, and certainly fell into the realm of being a calculated risk. Eidos kept the Championship Manager name, while Sports Interactive kept the engine, data, and everything else needed to make the games over the decade-plus. In retrospect, it seems obvious who got the better deal, but the nagging doubts were there. “In the end it went a lot better than expected,” Ov smiles. Helped by a loyal community—SI having redeemed itself with CM 03/04—the message was put out and spread loud and proud: Championship Manager is dead; long live Football Manager.

Of course, it’s never that simple, and Beautiful Game Studios’ platformer never did see the light of day, with the team instead producing something named Championship Manager, that looked like Championship Manager… but it wasn’t Championship Manager. Rather than dance on the grave of this dead branch of the series, the Sports Interactive team remains sympathetic. Though not entirely.

“It was shit,” Miles says. “But when you look at the people who worked on that game, there were some supremely talented people, like Dave Rutter who now runs the FIFA games at EA Sports. They had some great people, some of who we even nicked when they shut down. These are hard games to make.” Paul offers an explanation as to the impossible task at the foot of BGS: “To explain how difficult it was—if we wiped our drives clean and had to start the whole thing again without any code it would literally take years—about five years. They had to rewrite it. They were unlucky, those guys. Talented people thrown under a bus.”

Hammering home how intense it is to create the series, Miles puts on his coder’s cap. “The AI in Football Manager is actually pretty astonishing,” he says. “When most games might have 30 or 40 NPCs, we’ve got over half a million. When most games’ AI is making decisions every few seconds, the match engine in FM every single player on the pitch is making a decision every quarter of a second—potentially—there’s so much maths that goes into it. It’s stuff that we as a studio, as a team, should be really proud of having built on it for 25 years. We’ve built it up and up.”

The Football Manager series brings us in to the modern era, and it has seen Sports Interactive develop more and increase both in studio size—around 110 employees now, a slight increase on the initial two—and professionalism. Age is a factor too, of course, but for every negative—Paul can no longer play the game, being ‘too close to it’—there’s an unexpected positive, like long-term studio member Marc Duffy (hired to create SI’s first website when he was 14) bringing in design ideas from his own son. “We’ve become a heritage rock act, who just don’t play their greatest hits any more,” Miles laughs. “Endlessly making games, it’s absolutely non-stop.”

Football Manager is part of the modern lexicon now, cited in as many sporting articles as it is academic papers and birthing books, online communities—even a documentary film in 2014. It’s something the team is very proud of, as Ov explains: “That the game has reached the levels of being a cultural reference point—you see it mentioned in places where you least expect it, football articles with people commenting about us, everybody knows it—I think we take it for granted, but it’s very cool.” This universe of football was created as two brothers wanted it to be, and it grew into something incredibly influential. “We set out to create a game world experience,” Paul explains. “And we’ve managed to create a phenomenon without compromising that.”

The only question left, then, is if Miles and the brothers would ever want to try their hand at the real thing. Miles says no, he’s already involved in other areas and he’d be too rigid on tactics anyway. Paul could see himself getting involved if one of his children was in a team. And Ov? “I wouldn’t want to be a football manager,” he laughs. “I’d probably be too scared of upsetting people.”