The hidden tricks bringing game worlds to life

Under the surface.

Indie studio National insecurities was well on its way to completing its latest first-person murder mystery parody, 2000:1: A Space Felony. it had an eye-catching name, a publisher, and a rock-solid visual and thematic base it could use to play off audience expectations. there was just one problem: the centrifuge didn’t work. An astronaut jogs around a stark centrifuge, punching the air as he travels in an endless loop. This scene, from 2001: A Space Odyssey, is one of the most iconic in film history. And National Insecurities’ parody couldn’t replicate it. No matter what it did, the team couldn’t find a reliable, smooth way for the player to run along the centrifuge as it spiralled through space. Then lead developer, Lauren Filby had an idea.

Rather than attempting to create a special case for the player to be able to travel around the centrifuge while it was moving, she bent space around the player. When the player was outside the centrifuge, it would rotate as normal. However, as soon as the player entered the centrifuge, everything else in the game world would begin to rotate to ensure consistency of movement. This leap of logic is common to game development. Surprising in its requirements, bewildering in its utilisation, and essential to increasing the fidelity of a game’s world.

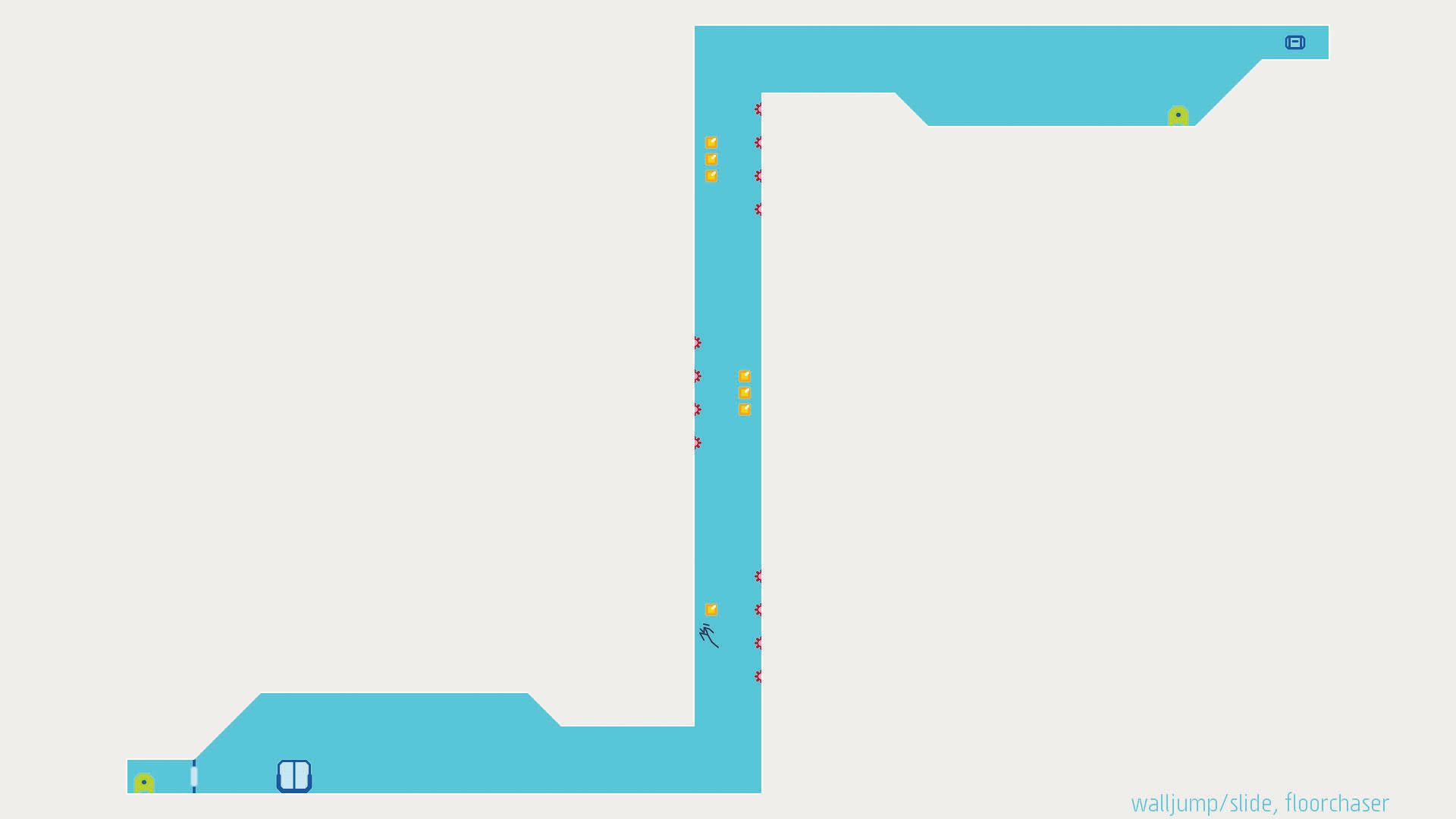

Raigan Burns tells me about Metanet Software’s quest to make N++ replicate the “smooth, clean look” of print graphic design in a platformer. “The main challenge we faced was the resolution of our visual medium,” Burns says. “Print looks so smooth in part because it operates at a very high resolution, typically at least 1,000 ‘pixels’ per inch [PPI], while computer monitors typically have fewer than 100 PPI. This was a pretty huge gap to cross, quality-wise, and the main reason why print design is so different from what you typically see on a screen.” Attempting to cross this gap in quality led Metanet Software cofounders Raigan Burns and Mare Sheppard to develop a rendering engine for their game, where every shape displayed is pure maths. “This means that all of the animations and graphics in the game had to be programmed line-by-line into the game’s source code,” Burns says. One of the most cutting-edge rendering solutions in gaming hides in the code of a 2D platformer.

One of the most cutting-edge rendering solutions in gaming hides in the code of a 2D platformer.

Gentle comedy adventure game Yorkshire Gubbins has a dynamic music system directly inspired by classic LucasArts adventure games, made possible by the recent expiration of a patent. Charlotte Gore composed the game’s themes, then a series of four-beat transitions to connect everything together. A subsystem in the game evaluates what’s happening at any time, what piece of music is needed, and the best transition to connect it to the previous piece. The result is a seamless, flowing score that echoes film almost as much as it does games past.

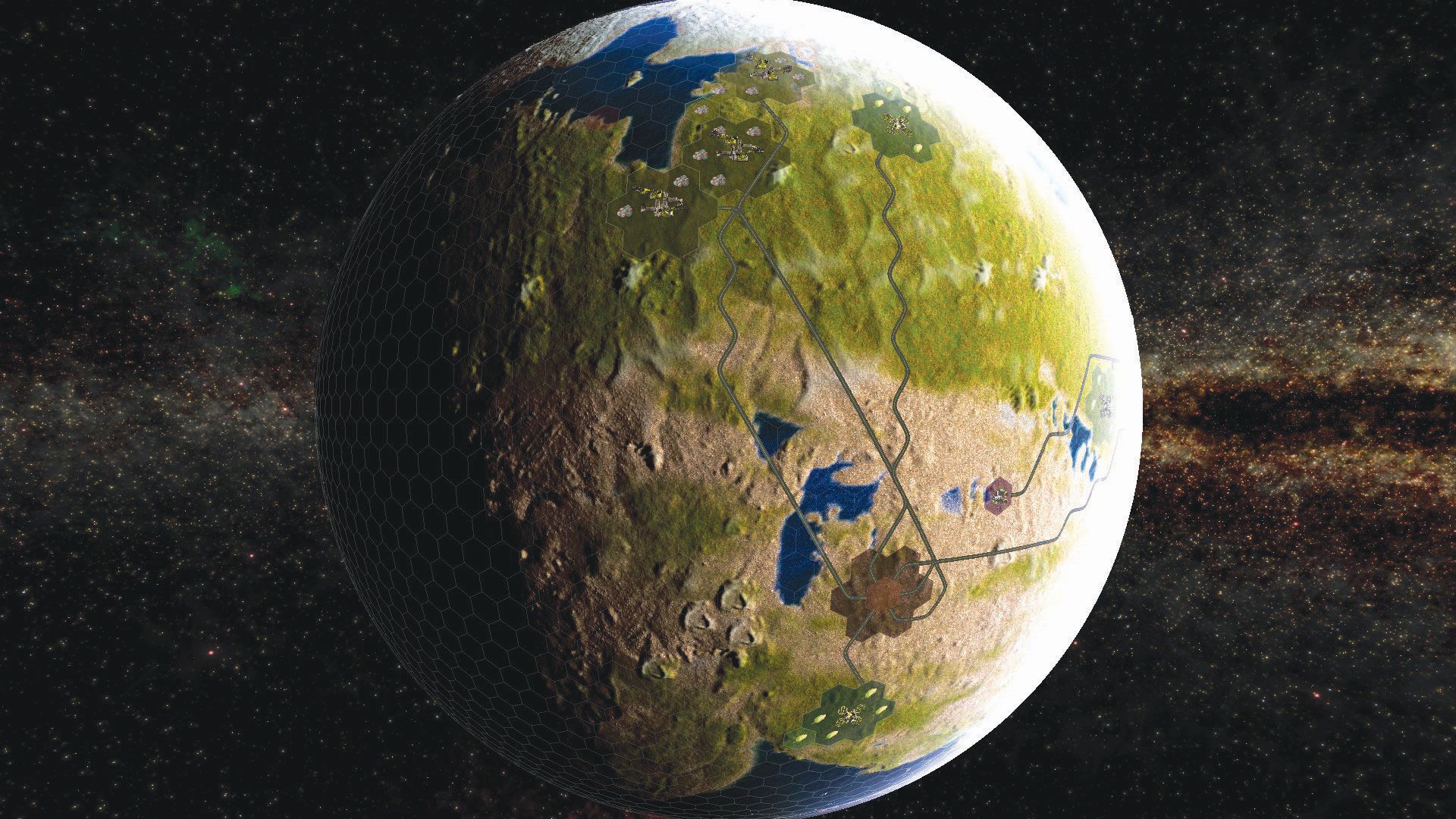

Early Access 4X strategy game Predestination contains spherical planets covered in hex grids. Putting a hex grid on a spherical surface is, apparently, impossible. Which is good, because the planets in Predestination aren’t spherical at all. They’re flat. “They wrap around on the X axis so you can rotate all the way around the planet and it appears to be a continuous sphere,” says lead developer Brendan Drain. “This doesn’t work on the Y axis, so you can’t have planetary poles. To solve this, we just lock the camera so you can only scroll up and down within certain limits and then the procedural generation algorithm places terrain at the top and bottom of the map to visually simulate polar regions.” The result is that players can rotate believably shaped planets, zoom down, and place structures on their hex grid surfaces.

James Earl Cox III, cofounder of You Must be 18 or Older to Enter developer Seemingly Pointless, found himself with an odd problem for his horror game about viewing porn as a kid in the early days of the internet. “People used to talk about how the images loaded too fast,” Cox says. Rather than artificially limiting the speed at which the ‘computer’ can load images, however, Cox took advantage of the monochromatic nature of the early hardware. “There are black squares layered on top of each image that slowly delete themselves over time to create the appearance of slow connection speed,” Cox says.

These are just a few of the many examples of the challenges surmounted to make something work ‘as intended’. Challenges solved by tricks. Tricks that, mostly, stay invisible. However, the more you learn about these tricks, the more apparent their importance becomes. Authentic game worlds aren’t created despite these tricks. They’re created because of them.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.