Rebuilding a 1998 PC just to play Half-Life

Beige is the new black.

This article originally ran in PC Gamer 328. The render above is by our art editor John Strike. Subscribe here and get great features like this sent to your door every month.

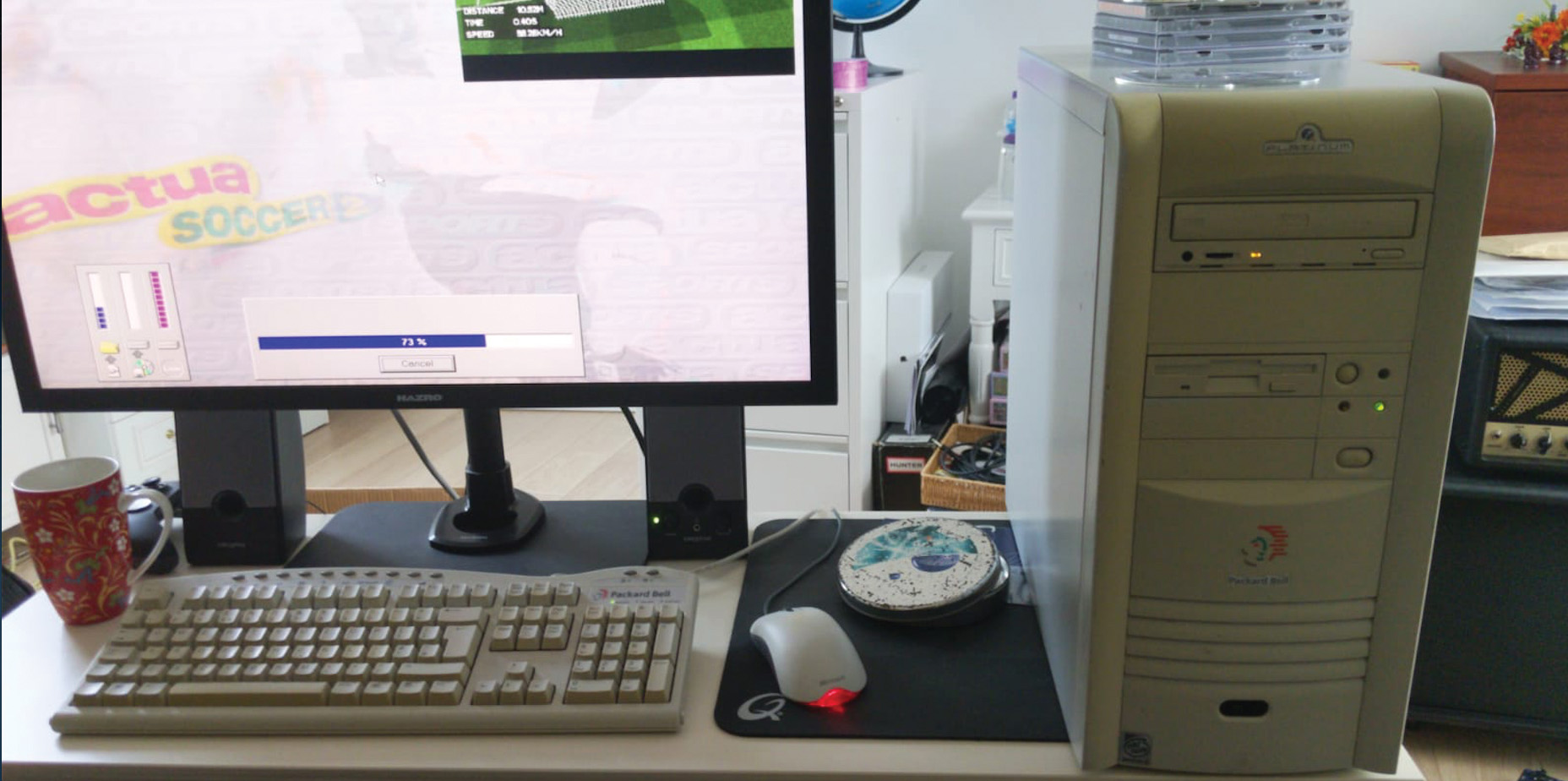

It all started with Black Mesa. Firstly, because the stars aligned in Christmas 1998 such that my first taste of PC gaming happened to be Half-Life, the best shooter ever made. Santa Claus delivered a personal computer to our home that year—a Packard Bell Platinum 350, since you ask. A 350MHz Pentium II lay within it. A 3DFX Voodoo 2 with 8MB onboard memory. 16MB of RAM and 6GB of hard drive space. These were formidable gaming specs, and when I was given the luxury of choosing a new PC game to accompany it under the tree I relied on the wisdom of PC Gamer, who sure were keen on this Half-Life game. That Christmas was magical. But that's not the point.

I mean to say, it all started with Black Mesa, the Source Engine reworking of Half-Life by Crowbar Collective. When it appeared on my radar back in 2013 I thought it looked like the perfect way to experience the game I'd confidently been calling the best shooter ever made—having played it just once, aged 12—once again. After 15 years of abstinence I’d once more allow myself to take in the giddy delights of creeping past the tentacle beast and watching Barneys plunge to their doom in broken elevators through the lens of this Source Engine remake.

I lasted about two minutes. That was all the time it took to realise that every slight deviation, every instance of minor creative licensing, was only going to wind me up. The Barneys all had different lines! The posters were slightly different! Some of the rooms were bigger/smaller than I remembered! This wouldn’t do.

No, this wouldn't do at all. I made a very serious promise to myself that day, having closed down the perfectly good Black Mesa mod. The only way I’d play my darling Half-Life ever again was in situ: the original game disc I'd kept all these years, running on a Packard Bell Platinum 350. So began a painstaking and indefensibly self-indulgent quest to source nearly worthless PC parts.

The keyboard and mouse were surprisingly easy to get hold of. Having set up eBay alerts for every bit of Packard Bell minutiae I required, I was directed to the very same 'board, complete with redundant multimedia controls, going for a princely £10. It arrived shortly afterwards, smelling faintly of someone else's house and, well, presumably working. I didn't have anything to plug its PS/2 connector into to check. I opted for a Microsoft Intellimouse to pair it with because—and I’m ashamed to write this—I can’t remember much about the original mouse that came with my first PC and I’m pretty certain we plumped for the Intellimouse quite quickly anyway. They're ten-a-penny on eBay too. Easy, this retro PC-sourcing lark.

Retro fit

The real difficulty began, funnily enough, when it came to finding a specific model of PC released 20 years ago in good working order. Retro gaming PCs are all the rage at the moment, and there's a growing cottage industry of PC builders who source old parts and practise the dark art of 'refurbishment' on them (in reality a can of compressed air and some homemade bleach solution to remove the yellowing on beige plastic). But what if you're not just looking for a retro gaming PC, but the retro gaming PC? After a year of eBay alerts and fortnightly searches, I hadn't come close. I was at such a low ebb that I considered hitting the 'Buy it Now' button on a Dell.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I also thought about building the machine by sourcing the individual parts, and I must now say in the strongest terms possible: don't do this. You've forgotten everything about hardware standards and compatibility from 20 years ago. You have no idea what chipset that motherboard you're looking at is, and there isn’t a damn thing on the internet about it to inform you. No one will help you if that Voodoo 3 doesn't fit, and good luck getting all the right cables to connect your miraculously compatible components which you’ve implausibly found working drivers for. Honestly, forget it. Buy a prebuilt PC which the seller confirms is in full working order. If they include the original recovery disc, that’s a massive bonus. You’ll need to buy your old operating system of choice otherwise, and although Windows 98 isn't quite as expensive now (£15-£20 from most sellers), it's an added cost you might initially overlook. If you want, you can even refurbish an old machine yourself by buying a £5 can of air and following one of the many questionable recipes for 'Retrobright' solution to bleach parts back to factory fresh—just know that PC Gamer accepts no responsibility for you ruining your floors, bathtub, hands and PC parts.

It came as quite a surprise when my exact make and model of PC materialised on eBay after a full year without leads. I stared at each shaky smartphone photograph on the listing with an almost pornographic fascination, barely conceiving the needle I’d found in eBay’s discarded goods haystack. The seller had listed it with a guide price of £400 to encourage private offers, and honestly I’d have paid it if it came to it. In the end, though, I sent an offer of £100 and spent the day worrying that I'd lowballed to such an insulting degree that my bridge with this seller was forever burned. He accepted it instantly, because you would, wouldn’t you, if some weirdo came out of the woodwork desperate for your unwanted two-decades-old computer. Thanks again, sync_it, and sorry about deleting all your old Champ Man 3 saves.

Sitting at a PC without an internet connection reminds you how easily distracting your modern gaming habitat can be

The fates had smiled on me. I'd secured some very specific pieces, and I hadn't even had to risk the one website that claimed to still be selling my original PC new, 20 years later. Still, two pieces elude me: the Packard Bell Milano 17-inch CRT monitor, and the recovery disc. I'll keep searching, of course, but I was especially disappointed not to fully immerse myself into 1998-o-vision with a CRT's characteristic display. Good CRTs are hard to find now—most have either been chucked, broken, or taken to recycling centres to fester away. Of those that appear on eBay, most predate my target Windows 98 era—there's high demand for Win95 screens and earlier, it seems. They're also heavy as all heck, which means delivery is a real issue—there are specialist couriers who deal with fragile items and know how to handle a CRT, however. Perhaps there's someone out there who's cared for a Milano monitor all these years, someone now ready to part with it. Until I find them, I must subject my retro rig to the indignity of outputting on a 32-inch IPS.

Never mind. The beating heart of the PC was just as it had been. Likewise my peripherals. What a perfect way to remind oneself what PC gaming was really, truly like 20 years ago. That's no small point—that era's been fetishised in recent years, evidenced by Kickstarter-funded odes to the Infinity Engine RPGs, and reboots of everything from Thief to Outcast. Not to mention Black Mesa, of course. What's clear when you press the power button on an old tower PC, hear the Windows 98 welcome chimes, and load a game's CD-ROM into the tray, is that we've forgotten much of the era's reality.

For example: first-person shooter control schemes were the wild west in 1998. By default, Half-Life's controls are bound to the arrow keys, of which left and right turn, rather than strafe. At least mouselook is enabled by default. Quake 2, released just a year prior, maps the mouse to moving forwards, while A and Z control your vertical view. Barbaric.

Revisionist History

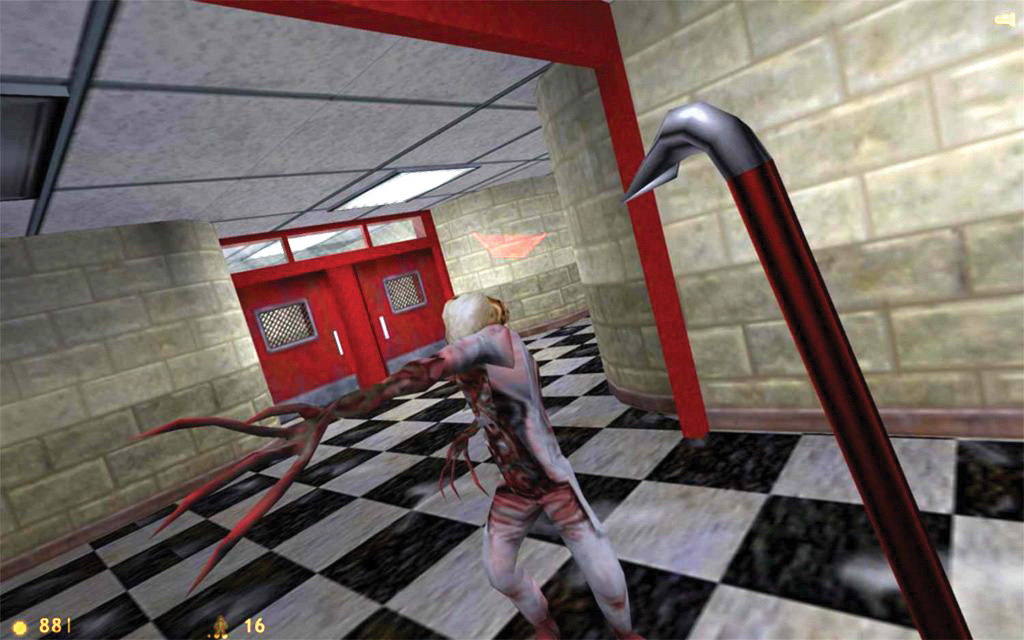

On the technical side, we've forgotten much about what games looked like when they released—for most people, running on a software renderer in 640x480 and still not hitting anything like 60 fps. The Half-Life you see in YouTube speedruns and Let's Plays, running at modern day resolutions, bears little resemblance to the one I lost myself in the Christmas it came out. That game is grainier, darker, and more atmospheric for it. Although hundreds of shooters have since aped Half-Life's setpieces, NPCs and storytelling techniques, Valve's vision stands as tall and impressive on this retro PC as it did on release. Half-Life was, and is, a place you go, rather than a game you play.

Perhaps the most profound realisation that comes from building an old PC and booting up a treasured memory is that I’d advocate every single PC gamer do the same thing. The nostalgia hit is absolutely worth all that e-trawling, but more than that, sitting at a PC without an internet connection (for goodness' sake don’t try to go online with Windows 98) reminds you how easily distracting your modern gaming habitat can be. There’s nothing to alt-tab out to and no Steam list of zero hours played shame. That feels like an important reminder.

Phil 'the face' Iwaniuk used to work in magazines. Now he wanders the earth, stopping passers-by to tell them about PC games he remembers from 1998 until their polite smiles turn cold. He also makes ads. Veteran hardware smasher and game botherer of PC Format, Official PlayStation Magazine, PCGamesN, Guardian, Eurogamer, IGN, VG247, and What Gramophone? He won an award once, but he doesn't like to go on about it.

You can get rid of 'the face' bit if you like.

No -Ed.