Permadeath and permabans: How 'losing' is changing in videogames

As we spend months and years integrating games into our daily lives, death and loss take on a new weight.

You were never supposed to take up residence in a videogame. There was an eight hour campaign, a passable multiplayer mode, and maybe an expansion if it sold well. Not so long ago, the idea of spending days, or months, or years occupied in the same digital world simply wasn’t part of the design. But now our most valuable gaming possessions are accounts and intangible digital goods, not the games themselves.

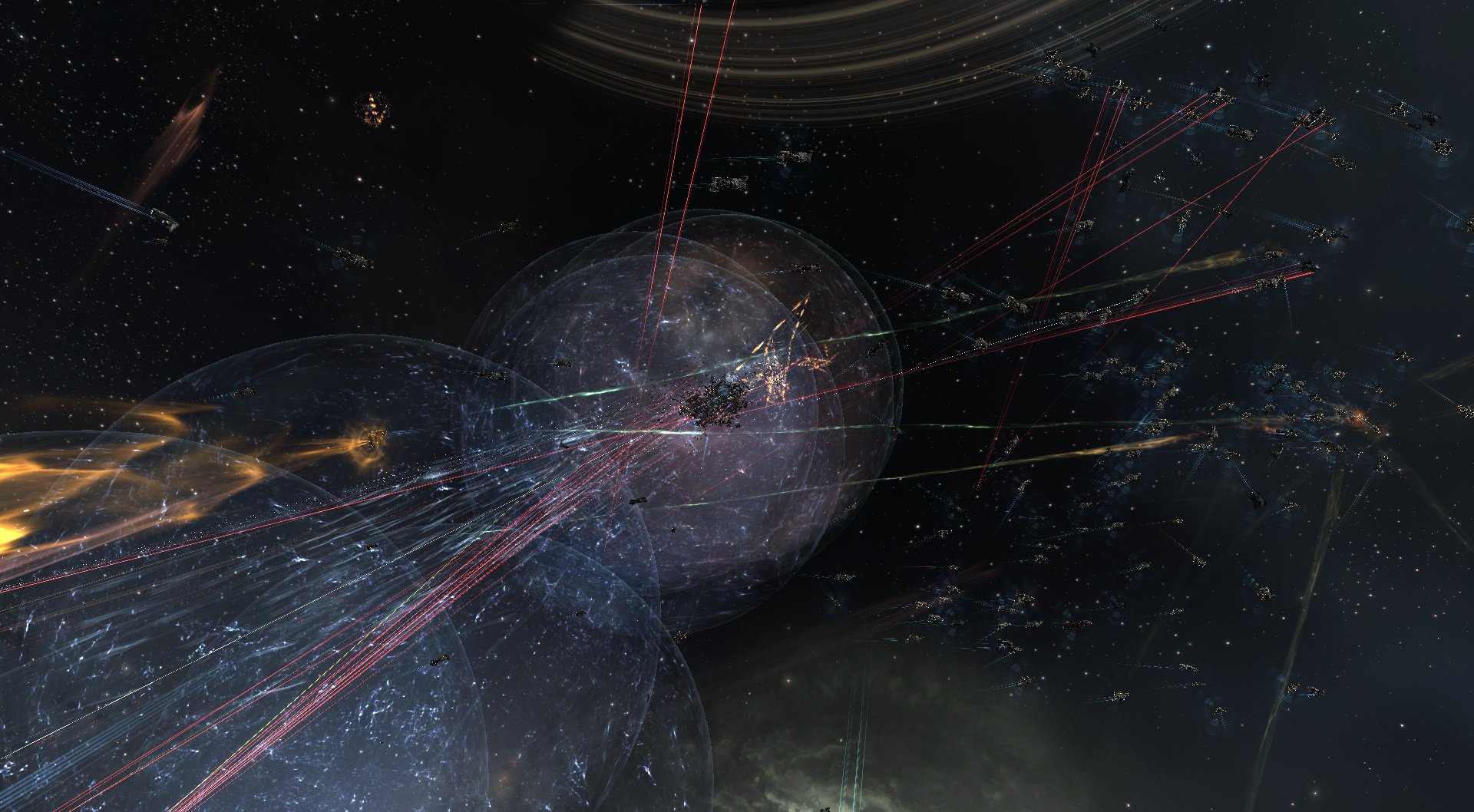

Today's biggest games are designed to keep players coming back again and again for life; slowly building a home, a community, and a fair share of equity. We see it reflected in League of Legends accounts with years of playtime, World of Warcraft characters running around with more digital assets than your average millennial, and EVE corporations holding a small nation’s worth of capital. Videogames have never been less disposable, and it’s wonderful that they can weave into a lifestyle. But that also means that sometimes disaster can strike.

“I died while doing Adria alone,” says Justin, a Diablo 3 hardcore player. “My anxiety over my impending death came out in voice chat as ‘I’m gonna dieeeeeee! Noooooo!’ This wasn’t forgotten, it happened last season and every once in awhile one of those fuckers brings it up.”

Hardcore Diablo 3 engenders drama with the inevitable promise that someday, somehow, your character will die, and they will disappear forever. Countless hours, dozens of ultra-rare items, gone in an instant. RPGs are built on the fundamental faith that your character will always be moving upwards, but that’s certainly not the case here.

“I had the character from the beginning of the last season. I think it had around 80ish hours,” says Justin. “Luckily, this was already deeper into the season. I already had another 70 waiting in the wings, and I just had to put my progression gear back on and I went back to farming with my friends. Though, every time I die, from disconnecting or my own fault, I feel like I shouldn't be playing hardcore ever.”

This isn’t a new concept. Diablo 2 had a hardcore mode, and games as old as Rogue were playing with permadeath long before the always-online age. But there are certainly different stakes in 2016. Diablo is a service. It will be marked with incremental new content for a long, long time. When your character dies, you’re not leaving a static, unchanging world behind. It feels bigger. And that’s the fun—hardcore players talk about their brushes with death like commiserable legends, filled with hubris or fate.

“The first barbarian I lost this season was so stupid, I was two-manning some rifts with a buddy, I knew it was my last rift of the night because I was starting to get pretty tired,” wrote Reddit user d3phext. “I lean back in my chair for a good stretch and yawn and when I look back my screen is red. Before I can do anything a serpent magus hits the killing blow. Seven level 65 augments lost to a yawn.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

That might sound like the most frustrating thing in the universe, especially when you’re losing hours of progress to something very silly, but they can end up being the most memorable moments in gaming.

“Whenever I get even close to death, I probably get the the biggest adrenaline rush I've ever felt. Hand-shaking and all. Given that I play to complete the season journey each season it's soul crushing to lose that kind of progress, especially with gems,” says Justin. “As much as it sucks, it's what I signed up for. After I get over the initial shock, I remind myself; ‘Hey this is what hardcore is, and it way more fun and exciting than normal mode.’ It's honestly the only game I've ever played that gives me a physical reaction.”

Loss in hardcore Diablo is the loss of time and digital value, but the stakes feel even higher in a game like EVE. In EVE Online, subscription time can be bought with real or in-game money, which gives a clear reference point for the actual monetary value of property. Reddit user TimmyTheNerd recounts a particularly harrowing time when he was made a target after failing to deliver a shipment for a particularly vindictive employer.

“I always flew alone, as I wasn't social and didn't have anyone to fly with. Well, my former employer finds me. One after the other he begins to hunt me down, taking out each of my ships. Everytime I undocked, he seemed to know exactly where I was and was always there to make me pay for losing his stuff,” he wrote. “This went out for two weeks before I decided it was time to take a break from EVE for a while. I'm pretty sure my former employer is waiting for the day I return to EVE so he can continue to dish out his punishment.”

Another EVE player named Tim, from the Netherlands, lost a mothership in EVE back in 2008 after getting ganked by a fleet from a rival corporation—which sent him all the way back to square one.

“I hadn't spent any 'real' money on EVE besides the sub fee for three accounts, and all the money for my Wyvern was acquired through level four missions, trading, and scamming. While not a big real money loss, it fucking stung for a few minutes, and I quit EVE for the weekend,” says Tim. “A mothership going down in 2008 was a big deal and I got a lot of sympathy mails from fellow super pilots and people asking me what had happened and even offering to pitch in for a new one. I met the guy who laid the final blow at Fanfest 2008 and we had a laugh about the whole thing.”

Like Justin, Tim accepts this reality because it makes the experience so visceral. It makes you care about death: the adventures are grounded in a greater reality.

If you play Grand Theft Auto or Assassin’s Creed or any other major videogame that doesn’t function with long-term consequences, you might find yourself crashing cars, or jumping out of airplanes just to see the animation. There aren’t any stakes. That character doesn't actually exist. There’s a fundamental disconnect between you and the person on the screen that you won’t find in hardcore Diablo or EVE. You may not feel like you're inside the game, but you sure as hell care what happens in it.

“I've played a lot of other games and tried some other MMOs but the stakes in EVE are what made it great to me,” says Tim. “I remember the excitement of buying my first battlecruiser after a few weeks, only to lose it in a level three mission and nearly quitting the game because of that. After a while you get the hang of it. I got this kill, a one-off in the history of EVE, the only time a mothership died in one hit. I talked a bit to the pilot afterwards and felt really bad for him, I think I even gave him some ISK. I knew that it could have been me just the same, losing a lot of hard work in the blink of an eye.”

Again, this is supposed to be fun. In Diablo and EVE you get punished, and die in hilarious tragedy. These are war stories you’re supposed to carry for the rest of your life. But that’s not the only way to lose everything in a videogame. Sometimes it’s no fun at all, especially when the stakes really do bleed over into your everyday life.

Banned for (digital) life

Dan Walton still won’t say exactly what happened. The Hearthstone pro who went by “Alchemixt” during his playing days was struck down with an out-of-nowhere permaban in early 2015. The charge? Win trading, or agreeing to win or lose a match in order to boost a player’s rank. Walton claims he was breaking the rules unintentionally, but he still lost his entire card collection, which he estimates constituted about $2,000.

“At the time that I announced my retirement I wanted nothing to do with the game anymore. I took a blow to my reputation, lost my account, and I felt terrible,” says Walton. “I felt like I was a positive force in the community and part of the old crew that helped launch competitive Hearthstone into what it has evolved into today. All of the sudden, this ban comes along and it is like none of that other stuff I contributed seems to matter anymore. This made me feel almost betrayed on some level.”

The door was open for Walton to return. Technically he could start a new account, accrue his card collection, and return to professional play—but he found it hard to muster that passion after all the baggage that comes with a competitive permaban. His brief career as a pro player was more or less ruined in one bad moment.

“If Blizzard banned me for account sharing [instead of win-trading,] then I would own it immediately and accept it. However, they took it a step further without any warning, notice, or speaking to me,” says Walton. “This really hurt my reputation and I almost let it ruin the gaming part of my life.”

Eventually, after the sting of his Hearthstone ban faded, Walton found a new place in the scene. Today he manages the Splyce Hearthstone team, a job that mostly consists of updating Liquipedia profiles, booking travel, and helping with events and social media. He enjoys his work, and is still close to Hearthstone. But naturally he still thinks about throwing his name in a tournament from time to time.

“When I was playing the skill level and the amount of preparation players put into the game was much lower than it is today. I realized this and accept the fact that I would most likely fall behind this curve. If I was still in the Hearthstone scene today as a player I would have tried to be more on the streaming/content creation side of things,” says Walton. “With all of that said I am at peace with everything now and I really enjoy being a part of Splyce. All of the staff and players there are great.”

If Walton's transgressions were a mistake, as he claims, it doesn’t seem particularly fair that you can lose a world of friendships, dreams, money, and connections after one slip up. I mean, sure, we’re talking about Hearthstone cards, but that’s still a ton of lost equity. But those were the rules.

Permabanning cheaters is how multiplayer justice systems have always worked, but in a business model founded on microtransactions—where, ostensibly, you’re paying Blizzard money for the ownership of cards—it feels a little more brutal. Just as quickly as dying in a game like Diablo can strip you of a hundred hours of accrued possessions, being banned can cut off more than a form of entertainment. It's losing a lifestyle.

This means something different in the digital era than it did before. It’s not like cheaters in professional Magic are getting their entire card collection confiscated. But for players like Walton or Reckful, a high-level WoW player who was famously banned for account sharing in 2014, everything's gone in a moment.

"Hi, I'm curycoo, long time dota player of over 6 years, with 5k hours in the game and around 2 thousand dollars spent. Today, I got vac banned on Dota," reads one reddit thread. The VAC Steam forum is full of similar sob stories. That's nothing new for online games, but being able to spend thousands of dollars on skins or items, only to lose them all, is.

And except in very rare cases, everything stays gone.

Only a lucky few have managed to return to a former life built around a game. League of Legends pro Nicolaj Jensen, for example, was banned for life by Riot for toxic behavior and allegedly DDOSing other players. He grew up, shaped up, and was lucky enough to be unbanned and become a rising star of professional League. Most players will never have that experience, whether they're pros who lose a livelihood or guild warriors who lose a 10,000 hour WoW account.

You could blame it on Twitch, or YouTube, or the economy, or the nature of big-budget game development, but the world has changed. You find your game, and your scene, and then you stay put. EVE, Diablo, and Hearthstone are platforms that can become crucial parts of people’s lives. Sometimes death is a part of the fun and sometimes it’s iron-fisted punishment, but either way, life and death in videogames means more than it ever has—how real it could one day feel is as exciting as it is frightening.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.